The following article by Ruy Teixeira, author of The Optimistic Leftist and other works of political analysis, is cross-posted from his blog:

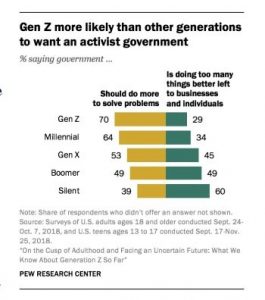

For all the attention paid to the Millennials, Gen Z (born after 1996) is coming up fast. They too will have a big effect on politics. As I have noted before, early data on the first tranche of Gen Z’ers coming into the electorate suggests that they will be as liberal as the Millennials and possibly more so.

This is confirmed by a new release from Pew that details some of this generation’s key views and preferences relative to older generations.

“One-in-ten eligible voters in the 2020 electorate will be part of a new generation of Americans – Generation Z. Born after 1996, most members of this generation are not yet old enough to vote, but as the oldest among them turn 23 this year, roughly 24 million will have the opportunity to cast a ballot in November. And their political clout will continue to grow steadily in the coming years, as more and more of them reach voting age….

Aside from the unique set of circumstances in which Gen Z is approaching adulthood, what do we know about this new generation? We know it’s different from previous generations in some important ways, but similar in many ways to the Millennial generation that came before it. Members of Gen Z are more racially and ethnically diverse than any previous generation, and they are on track to be the most well-educated generation yet. They are also digital natives who have little or no memory of the world as it existed before smartphones.

Still, when it comes to their views on key social and policy issues, they look very much like Millennials. Pew Research Center surveys conducted in the fall of 2018 (more than a year before the coronavirus outbreak) among Americans ages 13 and older found that, similar to Millennials, Gen Zers are progressive and pro-government, most see the country’s growing racial and ethnic diversity as a good thing, and they’re less likely than older generations to see the United States as superior to other nations.1

A look at how Gen Z voters view the Trump presidency provides further insight into their political beliefs. A Pew Research Center survey conducted in January of this year found that about a quarter of registered voters ages 18 to 23 (22%) approved of how Donald Trump is handling his job as president, while about three-quarters disapproved (77%). Millennial voters were only slightly more likely to approve of Trump (32%) while 42% of Gen X voters, 48% of Baby Boomers and 57% of those in the Silent Generation approved of the job he’s doing as president.”

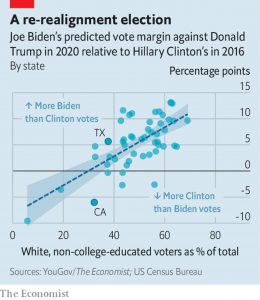

The Pew data on political preferences are supported by findings from the Nationscape survey. Nationscape data also show Gen Z’ers with even stronger pro-Biden and anti-Trump leanings than Millennials. This applies to both Gen Z as a whole and to the white subgroup of Gen Z, a fact of no small significance.