The following article by Ruy Teixeira, politics editor of The Liberal Patriot newsletter, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and author of major works of political analysis, is cross-posted from The Liberal Patriot:

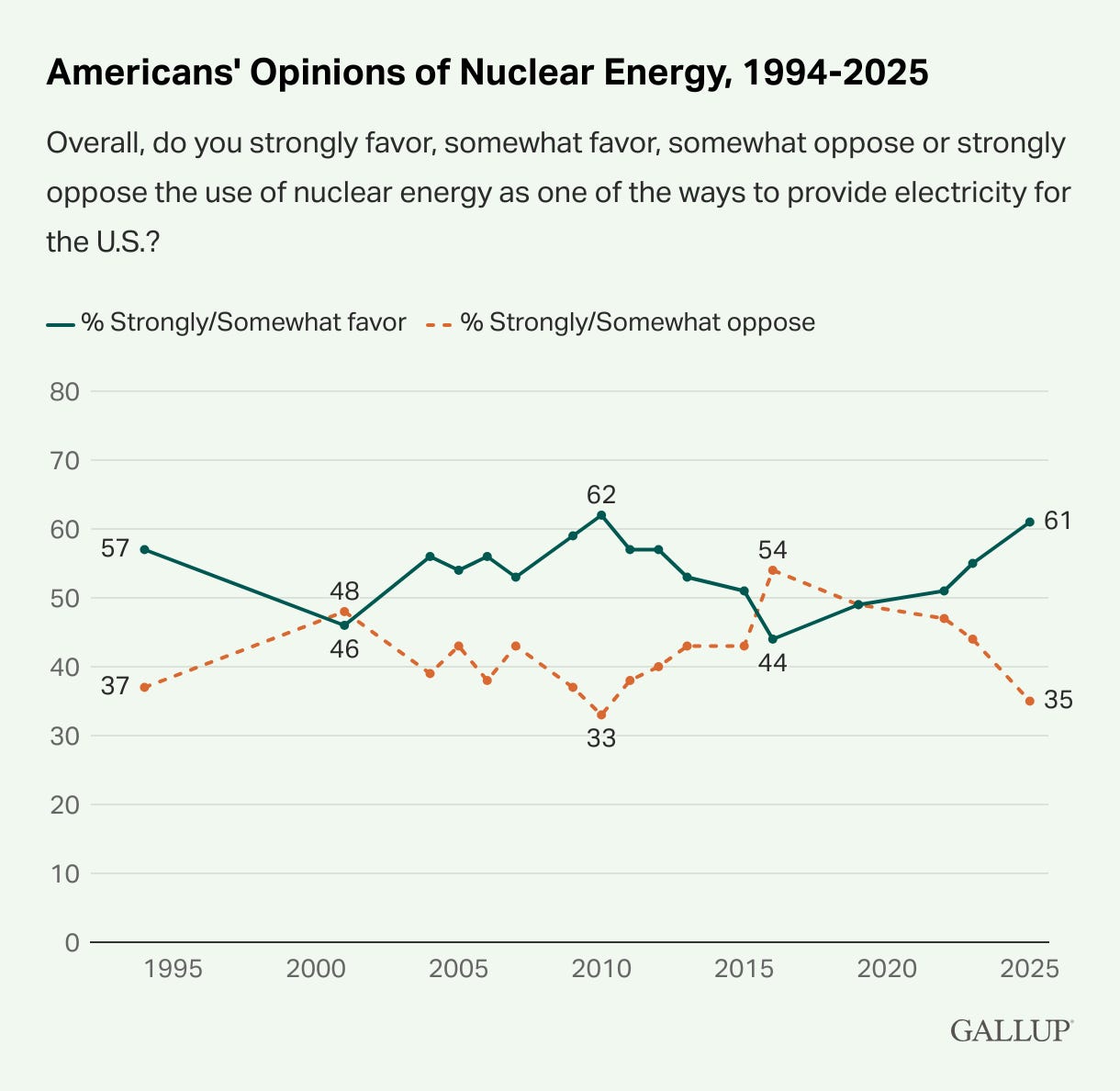

This just in: Americans love nukes! New Gallup data show attitudes toward nuclear energy doing a U-turn from negative views in the mid-teens to strongly positive views today. In less then 10 years, positive views have spiked by 17 points while negative views have plummeted by 19 points. That’s taken net support (favor minus oppose) from -10 to +27.

This is surprising but it’s worth asking why this is surprising. Nuclear power, after all, is a clean, carbon-free energy source in an era when the center-left is obsessed with eliminating carbon emissions. Moreover, nuclear can provide the necessary firm, baseload power to the grid that intermittent renewables (wind and solar) cannot. So where is—or has been—the love?

The answer goes back to the origins of the modern environmental movement and the apocalyptic strain that always lurked there, ready to be activated by an issue like nuclear power and, later, climate change. Here you need to make the acquaintance of a man named William Vogt.

Vogt was an ornithologist and ecologist whose experiences in the developing world had convinced him that economic growth and overpopulation would inevitably lead to civilizational collapse unless both growth and population were radically curtailed. He published his book-length polemic Road to Survival in 1948.

Vogt’s book had an enormous impact. It was a main selection of the Book of the Month Club, condensed by Reader’s Digest for its 13 million subscribers, translated into nine languages and immediately adopted as a textbook by dozens of colleges and universities. It became the best-selling book of all-time on environmental themes until the 1960’s and the publication of Silent Spring.

Vogt argued that humans were worse than parasites, who lacked enough intelligence to be truly destructive. But humans had used their brains to rip up nature and compromised their own survival to become richer. Only drastic measures could prevent worldwide environmental disaster (sound familiar?).

Vogt argued that beliefs in progress were weighing humanity down and were actually “idiotic in an overpeopled, atomic age, with much of the world a shambles.” He concluded that the road to survival could only lie in maximizing use of renewable resources and accepting lower living standards or reduced population.

In his language and outlook, one can see all the strands of apocalyptic environmentalism that were brought to bear, first on nuclear power, then on climate change. This especially applies to his description of the United States and its economic system. He said:

Our forefathers [were] one of the most destructive groups of human beings that have ever raped the earth. They moved into one of the richest treasure houses ever opened to man, and in a few decades turned millions of acres of it into a shambles.

He continued:

’Free enterprise has made the country what it is!’ To this an ecologist might sardonically assent, ‘Exactly.’ For free enterprise must bear a large share of the responsibility for devastated forests, vanishing wildlife, crippled ranges, a gullied continent, and roaring flood crests. Free enterprise—divorced from biophysical understanding and social responsibility.

Vogt’s outlook was enormously influential. Historian Allan Chase observed:

Every argument, every concept, every recommendation made in Road to Survival would become integral to the conventional wisdom of the post-Hiroshima generation of educated Americans…[They] would for decades to come be repeated, and restated, and incorporated again and again into streams of books, articles, television commentaries, speeches, propaganda tracts, posters, and even lapel buttons.

More benignly, Vogt’s book marked the evolution of traditional conservationism into environmentalism. Stripped of the apocalyptic verbiage, he was arguing that conservation of nature was not enough. The interdependence of man and nature meant that human activities could not be isolated and instead were having negative effects on the entire planet—wilderness, settled areas, oceans, everywhere. The balance of nature was being destroyed, dragging down the natural world and humanity with it. Restoring that balance, not merely conserving parts of the ecosystem, was the new meaning of being an environmentalist.

Also key to Vogt’s analysis was the concept of “carrying capacity”—how much the environment/planet could sustainably bear of a species’ imprint before disaster ensued. This was not precisely defined but it is easy to see the relationship of this idea to how climate change is conventionally thought of today.

The modern environmentalist movement kicked off in the early 1960’s with the 1962 publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (as with Vogt’s book, a Book of the Month Club selection). Carson was directly inspired by Vogt and in fact was a friend of his. Her book was primarily focused on the impact of synthetic chemicals, especially DDT and other pesticides, on the natural environment. Her prognosis was dire; not only were these chemicals destroying the balance of nature by disrupting ecosystems but they were also destroying the ecosystem of the human body. These chemicals have “immense power not merely to poison but to enter into the most vital processes of the body and change them in sinister and often deadly ways.” Moreover, these chemicals would “bioaccumlate” and have enhanced effects over time. Perhaps eventually even the birds would not sing (producing a “silent spring”).

The serialization of the book in The New Yorker took the middlebrow educated audience by storm. The chemical industry fought back, which only raised the profile of the book. The public furor led to a report on pesticides by President Kennedy’s Science Advisory Committee which, in 1963 issued a report largely sympathetic to Carson’s analysis. The general issue of pollution of the natural environment by commercial processes and chemicals received a huge boost from the intense and prolonged public discussion and from this the modern environmental movement was born. Protecting the environment and natural systems now had a truly mass base.