From Pema Levy’s article, “The 2020 Election Is Now About the Coronavirus. Here’s How Progressive Groups Plan to Win It: Democrats are taking early steps to spread word about Trump’s bungled response.” at Mother Jones:

“On March 12, a group dedicated to preserving and expanding the Affordable Care Act, called Protect Our Care, released the first political television ad that mentioned the coronavirus. It targeted Sen. Steve Daines (R-MT) for his opposition to Obamacare. Montanans already worried about health care were now also worried about coronavirus, the ad’s narrator intoned.

But Protect Our Care quickly realized that as a group focused on health care, they had a larger role to play, and broadened its messaging to include the country’s biggest contest by setting up what it calls its “Coronavirus War Room,” a messaging hub meant to hold Trump accountable for the ways he has made the crisis worse. Last week, it began blasting off memos targeting Trump to the press while also acting as a messaging clearinghouse for other groups. Protect Our Care also started hosting calls three times a week with progressive groups to get everyone on the same talking points…

“Our focus at Protect Our Care and the Coronavirus War Room is largely on the accountability piece and with that it’s almost exclusively focused on Trump,” says Woodhouse, a longtime Democratic operative. “You can’t wait until October to tell the American people about how roundly he screwed this up.”

…[Executive Director Brad] Woodhouse sums up the core messages pushed from the war room: “He screwed it up from the beginning, he hasn’t learned from his mistakes, he’s downplayed the crisis, he doesn’t listen to experts, and that continues to make the crisis worse.” You can see the strategy deployed in the emails his team blasts out, often three a day, which attack Trump on a range of issues, including the administration’s failure to prepare by ramping up testing and the manufacture of medical equipment and protective gear; its elimination of key offices and positions charged with pandemic preparedness; and by elevating Trump’s comments, like downplaying the need for ventilators, that contradict medical experts.”

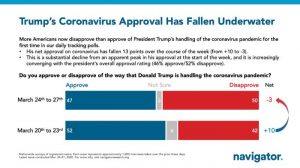

Levy explains, “To fight pro-Trump narratives, Democratic message warriors are looking for fresh data on how his words and actions are hitting home amid the crisis.” She adds, “Navigator Research, which is operated by two progressive polling firms, Global Strategy Group and GBAO Research and Strategy in consultation with the Hub Project, has put out monthly polls to help guide progressive messaging on a variety of issues. Two weeks ago, the project decided to scrap the monthly poll and set up a daily tracker to understand people’s attitudes toward the coronavirus and Trump’s handling of the crisis.”

She quotes Ian Sams, a Democratic strategist who consults with the Hub Project and Navigator Research: “We can’t handle this appropriately in real time as a progressive movement, as Democratic leaders, if we don’t understand how the public is processing it—because it is uncharted territory…We’ve never had 3 million people file for unemployment in a week.” Recent numbers show the situation is even more unprecedented: 10 million jobless benefit claims in two weeks.”

The Hub project “has captured data uncovering areas where Trump remains out of step with American opinion. When Trump floated the idea of prioritizing the economy over public health, the tracking poll released last Friday showed that people were more worried about their health and the health of those they know than the economy. Over the course of its first week, the poll showed Americans’ view of Trump’s overall handling of the crisis was trending downward. Small majorities last week believed Trump’s response has been “unprepared” and “chaotic.” Further,

Multiple Democratic super PACs have begun to run advertisements on Facebook and on television to hammer this message, though campaign finance law prohibits them from coordinating with progressive groups that are subject to fundraising restrictions. Pacronym, a Democratic super PAC affiliated with the digital firm Acronym, announced on March 17 that it would spend $2.5 million through April on Facebook ads to educate voters about “how the Trump administration’s chaos and incompetence have weakened the nation’s ability to respond to the coronavirus crisis.” The effort is focused on battleground states.

Priorities USA Action, another Democratic super PAC, began running television ads last Tuesday in the swing states of Florida, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. The ad splices clips of Trump downplaying the crisis with a growing chart showing the rising number of infections in the United States. The Trump campaign issued a cease and desist letter to TV stations asking them to remove the ad; the group responded by putting it on the air in Arizona as well. A version with updated numbers went up this week. On Wednesday, the group spent another $1 million on a television ad that contrasts Trump’s response with remarks Biden has made about how he would handle the crisis. It also began running a Facebook ad juxtaposing Trump and Biden.

“This is the most important issue in the country today,” says Katie Drapcho, Priorities USA Action’s director of research and polling. “I think it’s a defining moment for Trump’s presidency and the country. And our view is that it’s absolutely crucial that voters hear the facts about Trump’s inaction and misleading statements.”

In addition, “Unite the Country PAC, a super PAC started in 2019 to support Biden’s campaign, spent $1 million to broadcast an ad accusing Trump of failing in this time of crisis, and added another TV spot on the same…Protect Our Care, the group behind the Coronavirus War Room, launched new ads across Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania…”

Regarding the difficulty of Democratic messaging during the pandemic, Levy concludes that “It’s one thing to figure out how to attack Donald Trump, it’s another to do so without rallies or door knocking. It’s a problem for the Democratic nominee, but also for organizers behind voter registration and get-out-the-vote programs…Just as social gatherings have transitioned to FaceTime and Zoom, it seems certain that new forms of political organizing will be digitized.”