The following article by Ruy Teixeira, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, politics editor of The Liberal Patriot newsletter and author of major works of political analysis, is cross-posted from The Liberal Patriot:

Over time, Democrats have been hemorrhaging working-class voters, including and especially in the last election. A resolute, unconditional defense of government bureaucracies does not appear to be a promising route to getting them back in our current populist era.

But oddly, Democrats seem to have decided that hitching their wagon to government bureaucracies is just the ticket they need to storm back against Trump and GOP. Nothing illustrates this better than how they’ve mounted the barricades to defend USAID and each and every dollar it spends.

As was widely-reported, all USAID programs except for “life-saving humanitarian assistance programs” were paused on January 20th and all agency employees, except for a tiny handful, were put on administrative leave (some have subsequently been reinstated through court order). These actions are follow-ons to Trump’s Executive Order on “Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid.”

Democrats were outraged as well they might have been. USAID does much useful and important work and most of its employees surely deserve something better than being summarily laid-off during an audit of the programs they administer. Democrats took that outrage to the streets in a signature #Resistance move, where House and Senate Democrats rallied outside the USAID headquarters building and demanded to be let inside (to do….something), at which point bored security guards politely told them to get lost.

Of course, this got a lot of publicity but to what end? The truth is most Americans know very little about USAID and could care less about the USAID as an institution. And if you told them that USAID basically administers foreign aid programs, they would care even less.

The fact of the matter is that foreign aid is one of the least popular parts of the federal budget. Indeed, skepticism about foreign aid is one of the most consistent and durable findings of public opinion research. In a 2023 AP-NORC poll, 69 percent of respondents thought U.S. government spending in this area was “too much”; 20 percent, “about right”; and just 10 percent “too little.” In contrast, support for more spending in most domestic areas (healthcare, education, infrastructure, Social Security, etc.) is very strong.

And unsurprisingly, anti–foreign aid sentiment runs highest among working-class voters, precisely the people who have been defecting from the Democrats to Trump, and without whose votes the party cannot recover. Cutting foreign aid spending is about ten points more popular among voters without college degrees than among the college-educated.

Given these realities, it makes sense for Trump and Musk to go after foreign aid spending, as an exemplar of misallocated government resources that need to be “reevaluated and realigned.” This is particularly the case since it isn’t hard to find examples of USAID programs that appear to have strayed far afield from standard priorities like food, medicine and technical assistance. One example of many is a $1,500,000 grant to a Serbian organization called Grupa Izadji “to advance diversity, equity and inclusion in Serbia’s workplaces and business communities, by promoting economic empowerment and opportunity for LGBTQI+ people in Serbia.”

In fairness, these kind of grants do not take up a large portion of USAID’s budget but even a small number of them is enough to raise hackles among voters who are already suspicious that much foreign aid is either wasted or could be better-spent elsewhere.

OK, let’s recap the situation for which the outraged masses of Senate and House Democrats have taken to the streets.

1. Democrats are blanket defending an obscure institution in an anti-institutional era, where most institutions are regarded with intense suspicion. As David Axelrod remarked to Politico, apropos of the USAID situation:

[How] did the party of working people become a party of elite institutions?…Part of the problem for the Democratic Party is that it has become a stalwart defender of institutions at a time when people are enraged at institutions (emphasis added). And they become—in the minds of a lot of voters—an elite party, and to a lot of folks who are trying to scuffle out there and get along, this will seem like an elite passion.

Call it the institutions trap. Trump attacks an institution Democrats are identified with; Democrats feel obliged—pretty much no matter what it is—to defend it tooth and nail. But that simply reinforces Democrats’ brand as the institutional, establishment party, which makes them even more vulnerable to populist attacks and even less capable of defending those institutions Then Trump goes after another institution and the cycle repeats.

Reflecting this dynamic, congressional Democrats have rallied in several other places, including outside the Departments of Treasury and Education, implying that whatever auditing and attempted cost-cutting is taking place at these institutions is completely unjustified. That is their default assumption—the bureaucracies in question are doing a fine job. But the default assumption of the median working-class voter is that a good chunk of most bureaucracies are doing work that isn’t even needed and wasting considerable money in the process. Therefore, such voters are likely to have considerable initial sympathy for what Trump and Musk/DOGE say they’re trying to do.

Democrats should recall an important finding from New York Timespolling in the last cycle. Voters overwhelming believe that the political and economic system in America needs either major changes or to be completely rebuilt. Automatic, dogged defense of all institutional bureaucracies does not speak to that sentiment.

Not only that, Democrats are only succeeding in making themselves look ridiculous as they take to the streets in geriatric-led demonstrations to defend these bureaucracies….

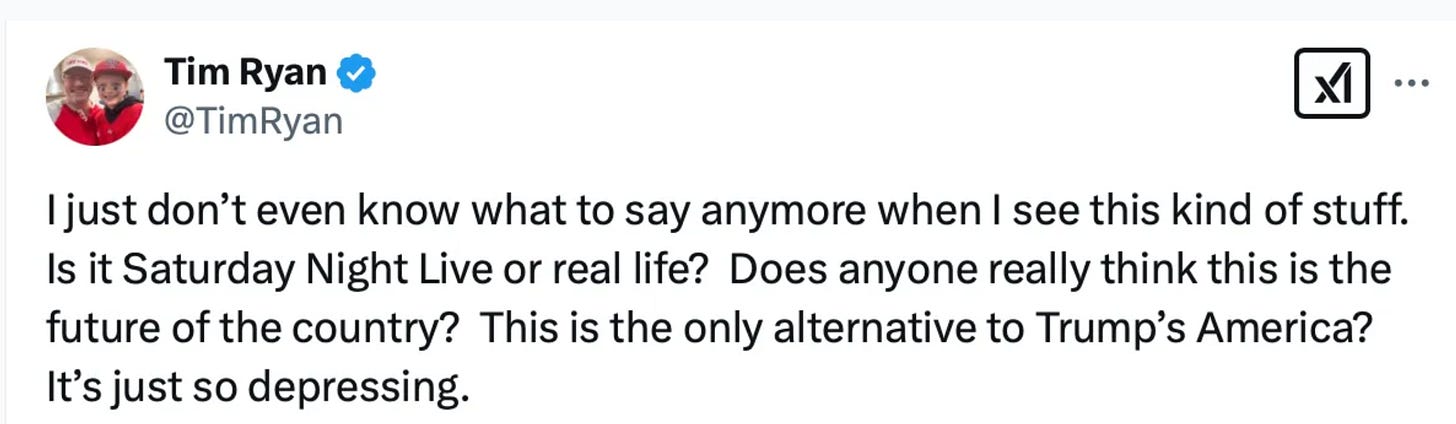

….As Tim Ryan, former Ohio House member and Senate candidate put it:

Yes, it is a bit depressing and certainly altogether implausible that these antics will succeed in reaching the working class voters Democrats need.

2. In USAID, Democrats are not only blanket defending an obscure institution, it is an institution that does one of American voters’ least favorite things: provide foreign aid. How much sense does it make for Democrats to hit the streets to defend USAID and pump up the issue politically when most Americans are indifferent to hostile to the programs they administer?

Not much! Axelrod again:

My heart is with the people out on the street outside USAID, but my head tells me: ‘Man, Trump will be well satisfied to have this fight…When you talk about cuts, the first thing people say is: Cut foreign aid.

You don’t fight every fight. You don’t swing at every pitch. And my view is—while I care about the USAID as a former ambassador—that’s not the hill I’m going to die on.

Words of wisdom, should Democrats care to hear them.

3. Finally, not only are Democrats blanket-defending an obscure institution that does something American voters don’t care about, they are defending without offering any hint of what they would preserve and what they would get rid of in terms of what USAID does. That implies that everything is working perfectly at USAID and all the programs are vitally needed, when clearly that is not the case.

Voters want big change in their institutions; it doesn’t make sense to insist that no change is needed, especially in an area like this. Bill Clinton once said: “Mend it, don’t end it” in a different context. That spirit of open reform is desperately needed here and elsewhere as Democrats try to resist Trump’s excesses.

And there will be many! Democrats should show some common sense in what they spend their political capital on as Trump ramps up his various institution-bending schemes. Given that even the most attentive political junkies are having trouble keeping track of all the things that are going on, we can safely assume that the typical working-class voter has very little appreciation for these intricacies—much less whether they amount to a “constitutional crisis”—and mostly knows Trump and Musk are shaking things up in government bureaucracies. That’s not necessarily a bad thing in their book, until and unless it starts to affect them personally.

That’s really the key and how Democrats can get out of the current “institutions trap” that brands them as the establishment party in an anti-institutional, populist era. Trump is pretty much guaranteed to do many things that are genuinely unpopular and impinge upon voters’ lives in a way that angers them in areas like health care, education, and the cost of living. Democrats should reserve their big guns for those situations. That should make them politically stronger over time and, paradoxically, make them better able to restore worthwhile USAID and other government programs over time and get many of those workers back to work.

In contrast, their current grandstanding on the USAID shutdown and other DOGE monkey business will likely do those programs and those workers no good. As that great American, Casey Stengel once remarked: “Can’t anybody here play this game?” We’re still looking Casey, we’re still looking.