The following article by Democratic strategist Robert Creamer, author of Stand Up Straight: How Progressives Can Win, is cross-posted from HuffPo:

“Conor Lamb’s success could provide a blueprint for other Democrats in tough races.”

“She is part of why [Democrats] have this incredible brand obstacle to overcome in state after state.”

This was the chorus among the pundit class in the wake of Lamb’s upset victory in the special election earlier this month to represent Pennsylvania’s 18th Congressional District.

According to them, the fact that Rep. Nancy Pelosi is the face of House Democrats diminishes Democratic chances of winning many swing districts and regaining control of the House this fall. Or so many Democrats would have to publicly disavow Pelosi over the course of the campaign that she’d have to step aside after the midterm elections.

Some fret that the House minority leader does not present the right “face” for the Democratic Party, or that she’s too old, or that the GOP has made her toxic to many white working-class voters. A small group of Democratic lawmakers, some of whom have their own ambitions for House leadership, agree.

But these critics seem completely unaware of the actual dynamics of midterm congressional elections. And Lamb’s win in Pennsylvania helps demonstrate why they’re wrong.

The bottom line is simple: The fact that Nancy Pelosi is their House leader is a huge net positive for Democratic candidates this fall.

Unpopular House Leaders Don’t Matter

Of course, all congressional leaders have positives and negatives. Even though she was brought up in an ethnic Italian family from Baltimore, Republican attacks have managed to convince some white working-class voters that Pelosi is a “San Francisco liberal” who doesn’t share their culture or values.

Nationally, voters with negative opinions of Pelosi outstrip the number with positive opinions ― as in true for all the other current congressional leaders. But this isn’t surprising. Fewer than 20 percent of voters have a positive opinion of Congress as an institution. And Republican Speaker Paul Ryan has virtually the same net negative rating nationally as Pelosi.

More importantly, when CNN looked at the relationship between the popularity of congressional leaders and the outcomes of midterm elections, it found no correlation whatsoever.

In 1994, Rep. Newt Gingrich had net negatives of 8 percent. In other words, voters with an unfavorable opinion of him dominated those with a favorable opinion by a margin of 8 percentage points. He was considerably less popular at the time than Democratic Speaker Tom Foley. But the GOP picked up 54 seats that fall and won control of the House for the first time in 40 years, and Gingrich became the speaker.

By 1998, Gingrich’s popularity had plummeted further, but the GOP retained control of the House. While it did lose some seats that November, the biggest factor was not Gingrich’s lack of popularity. It was President Bill Clinton’s soaring approval ratings based on the strength of his economic successes.

In 2006, led by the relatively popular Nancy Pelosi, Democrats won back control of the House – this time because President George W. Bush’s approval ratings had cratered as a result of the Iraq War and his unsuccessful attempt to privatize Social Security.

In 2010, Republicans roared back into control, winning 63 new seats. But their leader, Rep. John Boehner, had a pre-election approval rating of -7 percent. Pelosi’s net negatives were also high. The GOP wave had nothing to do with the leaders’ relative popularity. It was driven by the unpopularity of President Barack Obama and the newly passed Affordable Care Act.

In 2014, both Boehner and Pelosi again had net negative ratings in the polls. But Obama’s continued unpopularity was the overriding factor and Democrats lost a dozen seats.

In short, while midterm outcomes have no correlation with congressional leaders’ approval ratings, they do correlate with the president’s popularity. In 2018, President Donald Trump’s numbers are the worst in a generation.

How Democrats Win In 2018

Two groups of voters affect the outcomes of elections.

First, there are the persuadable voters. These are people who generally vote, but sometimes they pick Republicans and sometimes they choose Democrats.

Second, there are a party’s mobilizable voters. These are people who would tend to vote for a particular party, but are unlikely to make the effort unless they are especially energized by the campaign or overall political situation. For Democrats this year, they include the many voters who were “woke” by Trump’s victory in 2016. Remember, if everyone in America always voted, Democrats would almost always win, since Americans broadly support the progressive Democratic agenda.

Also included among these persuadables and mobilizables are the 10 percent of the voters who actually switched their presidential choice from one party to another (or nothing) between 2012 and 2016. One analysis found that 4.3 percent of voters changed from Obama to a third party or did not vote. Some 3.6 percent switched from Obama to Trump. Finally, 1.9 percent moved their votes from Mitt Romney to Hillary Clinton.

The analysis found that most voters in all three subgroups lean left economically and respond well to a strong progressive economic message. It found that moving to the right on economics does not help Democrats with any of these groups ― while it risks losing some voters and demoralizing the energized base, especially among young adults.

It also found that most Obama-Trump voters who currently plan to stay with the GOP are more conservative on cultural issues ― but progressive on economics.

Even if they tried, Democrats couldn’t convince these voters that Democrats are more “nativist” and conservative on cultural issues than Trump and the GOP. What’s more, the Romney-Clinton voters are disgusted by conservative cultural appeals. And whatever Democrats say, Republicans will charge Democrats with being too “liberal” on these issues anyway.

Any attempt to down play cultural issues like immigration, LGBTQ rights, civil rights, women’s rights and gun violence would also demobilize the Obama-third party/no vote group.

The conclusion is clear: Democrats win by projecting a strong, populist economic message, including a heavy emphasis on health care. And they win by refusing to hedge on immigration, women’s rights, civil rights, etc. ― and by framing the debate in terms of values.

That is exactly the strategy that Nancy Pelosi has charted for the Democrats in the House.

She is also a powerful inspiration for persuading and mobilizing voters. Pelosi is especially energizing to women – probably the most critical element in the massive resistance to Trump. Her commitment to a progressive message is also key to holding onto the progressive core of the party and attracting young people.

Pelosi Is The Organizer Democrats Need

Since the popularity of congressional leaders isn’t a critical factor in which party wins elections, what qualities does a congressional leader need to increase the odds of victory?

It turns out that the chief role of congressional leaders is not to be the “face” of their respective party. It is to be a strategist, organizer, fundraiser and, above all, unifier of their forces, leading them into battle.

On that front, Pelosi has excelled.

The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) has now recruited solid candidates to run in 100 of the 101 districts that it targets as in play this year. All but a handful of Republican incumbents ― even in very red districts ― have Democratic challengers. And Democratic fundraising during this electoral cycle is setting all manner of records, with no signs of letting up.

Pelosi herself is a prodigious fundraiser, bringing in $50 million personally for Democrats in 2017 alone. Since entering the Democratic leadership in 2002, according to DCCC records, she has personally raised an unprecedented $643.5 million for Democrats.

Pelosi meets regularly with scores of progressive organizations to seek their advice and unite the progressive movement.

And she does the hard work necessary to create a populist-progressive message for the fall. Recently she has undertaken a tour of a dozen cities to partner with progressive allies and raise awareness of the actual impact of the GOP tax law ― that over 83 percent of its benefits go to the top 1 percent and are paid for by stealing from Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security and a tax increase on many middle-class families.

She has also helped sharpen that narrative with her brilliance as a legislative leader. She is better than any other congressional leader in modern history at holding together her caucus, because she understands the interests of every member ― and knows how to aggregate those interests into a common progressive agenda.

The now very popular Affordable Care Act was largely passed as a result of that legislative skill, and she held 100 percent of the caucus to defend it last year. As speaker, she passed legislation to rein in Wall Street after the financial collapse of 2008 and pushed through the $787 billion Recovery Act of 2009 that saved or created millions of jobs ― not to mention dozens of other major initiatives. In 2005, she led the then-minority party’s successful fight to stop President Bush’s attempt to privatize Social Security.

Pelosi again made headlines in February 2018 after smashing a 109-year-old record for her eight-hour speech on the House floor in support of Dreamers.

In the Pennsylvania special election, Republicans tried desperately to tar Lamb with the “liberal” Pelosi. They sought to use her to advance their broader negative narrative about the Democratic Party, and they promoted the GOP tax law. Their strategy failed on all points.

At the same time, the DCCC invested dollars. Progressive organizations and especially the labor movement mobilized on the ground. Lamb delivered a populist-progressive economic message. He talked about values. He projected the qualities of leadership that are decisive for swing voters.

Lamb won the district, even though Trump had taken it in 2016 by 20 percentage points.

The attacks on Pelosi didn’t move persuadable voters. Neither did they stoke the Republican base to generate more turnout. Republican candidate Rick Saccone’s vote was only 52 percent of Trump’s total. Lamb got 79 percent of Clinton’s vote.

This fall there are 114 GOP-held seats that are more competitive for Democrats than Pennsylvania’s 18th District.

If Democrats are successful in catching the anti-Trump wave and channeling it into victory on Nov. 6, it will not be in spite of Nancy Pelosi. It will be because Democrats in the House chose one of the most effective message strategists, organizers, fundraisers and political generals in modern American history to be their leader.

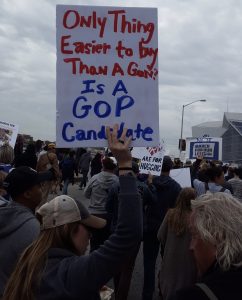

A sign in the Atlanta March for Our Lives (public domain photo)

A sign in the Atlanta March for Our Lives (public domain photo)