Fewer than 100,000 people had such plans at the end of last year, according to state insurance regulators, but the Trump administration says that number will jump by 600,000 in 2019 as a result of the changes. Some brokers are taking advantage, selling plans so skimpy that they offer no meaningful coverage. And Health Insurance Innovations is at the center of the market. In interviews, lawsuits, and complaints to regulators, dozens of its customers say they were tricked into buying plans they didn’t realize were substandard until they were stuck with surprise bills. The company denies responsibility for any such incidents, saying it’s a technology platform that helps people find affordable policies through reputable agents.

The authors note the experience of the Diaz family, a Phoenix couple with a moderate income who had one of these ‘junk insurance’ policies, expected to pay a modest deductable, but ended up with an out-of-pocket bill for $244,447.91, following the husband’s heart attack. Faux, Mosendz and Tozzi continue:

The ACA was designed around a fundamental economic bargain: Insurance companies would no longer be allowed to deny coverage to people who were already sick, and policies would have to cover a broad set of benefits, including prescription drugs, maternity care, and hospitalization. In return insurers were guaranteed that consumers would buy coverage or face tax penalties, and that subsidies would be available for people who needed them. The approach spread the financial risk of getting sick and aimed to guarantee that no one with insurance would have to worry about being bankrupted by necessary care. Preserving the bargain was essential, though; too many exceptions, and the edifice would crumble.

When the Republican-controlled Senate failed in 2017 to pass Trump-backed legislation that would have gutted the ACA, the administration instead seized on the loophole allowing consumers to buy certain noncompliant plans. Trump used an executive order to extend the time limit for temporary plans, which he and other Republicans talked up as a potential solution for cash-strapped consumers. Healthy people, they argued, could save money by buying policies that didn’t cover perceived nonessentials. “These plans aren’t for everyone, but they can provide a much more affordable option for millions of the forgotten men and women left out by the current system,” Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in August 2018.

By then, the ACA system was already wobbling. Aetna Inc. and some other big insurers had been dropping off the state exchanges created for consumers to buy compliant plans, leaving a void that “junk insurers,” as critics tagged them, rushed to fill. A recent study by Sabrina Corlette, a research professor at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute, showed that ads for such plans often appeared at the top of internet searches for the government-run marketplaces. Health insurance also became the most common product pitched in robocalls—responsible, according to call-blocking service YouMail, for 387 million calls this April alone.

The article goes on to detail how the Phoenix couple, who were inexperienced and unaware of the complexities of health insurance options, took the sales pitch of the insurer in good faith. The couple believed that the plan they bought was comprehensive. But when the bills began arriving, only then did they learn:

The Everest plan didn’t cover preexisting conditions, limited the number of doctor visits, and capped hospital coverage at $1,000 a day. It allowed a maximum of $250 per emergency room visit and $5,000 per surgery, not nearly enough to cover the usual cost of those services. Most benefits didn’t kick in until the $7,500 deductible was met. And the listed maximum total payout of $750,000 was misleading: It didn’t mean the Diazes’ bills would be covered up to that amount after they paid the deductible; it just meant that if Marisia underwent, say, 150 surgeries, she could get $5,000 for each, leaving her to cover millions of dollars in additional bills.

The Diaz family has filed a lawsuit, which could take years to resolve. Meanwhile they have to live with the uncertainty and stress that comes with the very real possibility of bankruptsy, threatening bill collectors and reductions in their already modest disposable income. They are not alone, as the authors write:

Similar stories aren’t hard to find. Complaints to the Federal Trade Commission obtained by Businessweek via the Freedom of Information Act detail numerous cases of HIIQ customers buying medical insurance they believed was comprehensive, then having their claims rejected or barely paid out. “I feel me really dumb,” wrote one person who’d found out her ADHD medication wasn’t covered. Another customer said she was reminded of the John Grisham novel The Rainmaker, in which an insurance company has a policy of rejecting every claim. Trudy Slawson, a 65-year-old in Great Falls, Mont., who bought an HIIQ-administered plan in 2016, thought she had comprehensive coverage until getting a surprise bill for $60,000 after her husband’s emergency gallbladder removal. The insurer paid only $100. “I believed what they were telling me,” she says.

Some brokers who’ve worked with HIIQ have run into trouble with regulators. The Massachusetts attorney general is investigating HIIQ and at least one brokerage that formerly sold for the company over what she calls misleading tactics. “You sell bad products to people under false terms,” an anonymous reviewer on indeed.com wrote of the brokerage. “You get paid well if you scam enough people.”

HIIQ doesn’t directly employ brokers, but the company says it goes to great lengths to ensure that agents are honest with customers, including by providing training, running background checks, conducting site visits, and staging phone calls from secret shoppers. Those who break the rules can be kicked off the platform. “HIIQ has diligent vetting and effective ongoing compliance monitoring,” Elizabeth Locke, an attorney representing the company, wrote in a letter to Businessweek. Last year, HIIQ settled a 43-state investigation into broker sales practices by agreeing to pay $3 million and monitor salespeople more closely, without admitting wrongdoing.

A recent FTC lawsuit raised further questions about how closely the company has been watching its brokers. Filed in November 2018 in federal court in Fort Lauderdale, the suit sought to shut down a group of boiler rooms run by a flashy 35-year-old named Steven Dorfman. The FTC said he’d swindled tens of thousands of people out of more than $100 million by passing off “sham” insurance policies as comprehensive health insurance, spending the profits on private jet flights, a white Lamborghini Aventador, a black Rolls-Royce Wraith, and a $300,000 wedding in Bal Harbour, Fla. One former customer service manager told the commission that Dorfman’s operation fielded as many as 3,000 complaints a day.

Multiply these examples by thousands, and you begin to get a painful sense of the daily cost of junk insurance all across America. This is the Trump/GOP “alternative” to strenghtening Obamacare, a swindler’s paradise and a nightmare for all working people who make the mistake of buying one of these junk policies.

“On June 14,” the authors note, ” Trump held a ceremony in the White House Rose Garden to announce a new policy that lets employers steer as much as $1,800 in tax-exempt funds to their employees instead of offering them comprehensive health plans.”

Trump, the Republicans and their insurance company contributors have built their phony ‘alternative’ on the dubious proposition that all health care consumers have the time, inclination and ability to analyze all of the complex, small print provisions that limit coverage, compare it to dozens of other policies, and decide what is best for their family. It’s the myth of the fully-educated health care consumer with oodles of free time made universal. “Why of course, everyone in the glorious free market will fully understand everything in their trust-worthy insurance policies.”

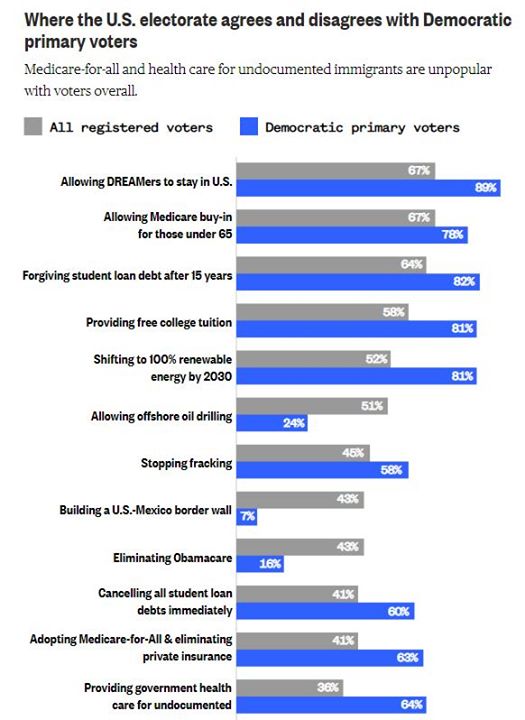

It will continue to get worse as long as Trump is president and Republicans control the senate. The only political remedy for preventing further such disasters on a massive scale is a public option alternative to private insurers. Medicare for anyone who wants it is a credible beginning, a first step toward real health security for every American. Only one political party stands for that, and Democrats now have to make the sale.