Since the 2018 elections there have been a substantial number of articles that analyze the white working class and how it may vote in 2020. But, at the same time, there have been very few articles that propose specific, targeted communications and advertising strategies whose aim is to weaken Trump’s hold on his white working class support.

The Daily Strategist

Chris Truax, a self-described Republican opinion columnist, shares some unsolicited advice for Democrats at USA Today. Among his observations:

Like it or not, the Democratic party has had greatness thrust upon it. Every American who believes in the basic foundations of the American experiment, things like the rule of law, the Constitution and an apolitical Justice Department, now has a stake in who Democrats nominate in 2020. So please stop telling fellow travelers like me to mind our own business and start taking on board some of what we are saying. The next president of the United States is everyone’s business, and we can’t afford to screw it up. Again.

A fair point. It’s up to Democrats to pick their best candidate. But many non-Democrats have a stake in that decision. Getting down to the nitty-gritty of Electoral College considerations, Truax writes,

America needs you to focus. Democrats’ first thought in the morning and their last thought when they fall asleep at night should be, “How will this play in Erie, Pennsylvania?”

There are four states that matter in 2020: Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Florida. Win three out of four of those states and Trump is a one-term president. No matter how popular something might be with activists in Los Angeles or donors in Manhattan, it’s dead weight or worse if it isn’t a winner with Rotary Club members in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

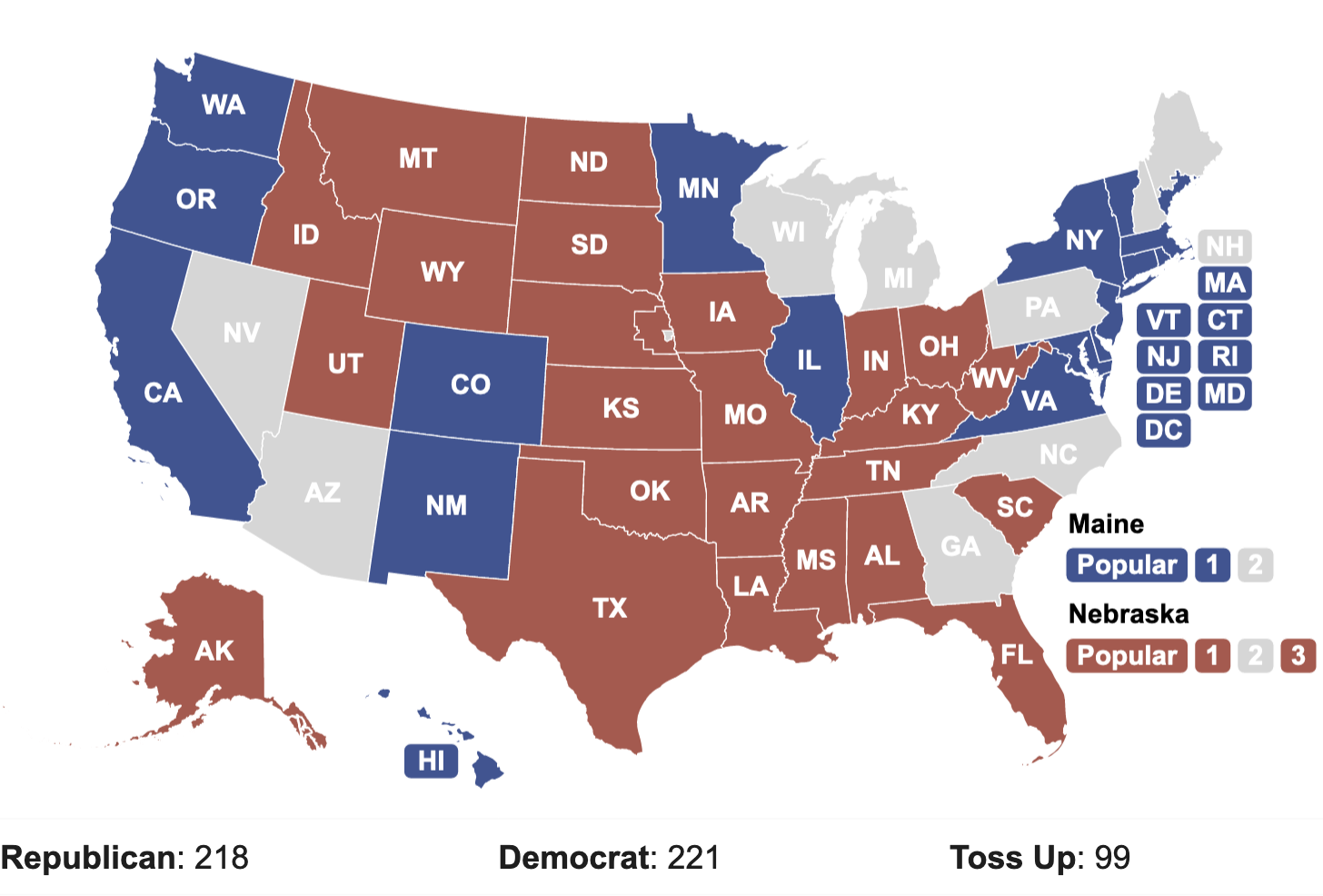

Those are, indeed key 2020 swing states with the most electoral votes as of this writing. You could substitute Arizona or North Carolina which have more EVs than Wisconsin, per Taegan Goddard’s interactive map flagged by Ed Kilgore yesterday. That could change some over the next 15 months, but probably not by much.

Here’s where Truax’s argument gets a little debatable for many Dems: “So don’t treat this like a base election. Democrats are already guaranteed a nominee that will excite their base and drive a big turnout. His name is Donald Trump.” That seems a little oversimplified. Dems can’t take their base for granted. Many factors could dampen base turnout. Besides, if Dems have a real shot at expanding their base in 2020 – and there is every reason to think they do – then they have to work it, as well as mine the universe of persuadable voters.

Truax also has some strong opinions about the real-world importance of energizing voters with “bold” policies:

Getting activists “excited” by bold policy positions is a waste of time. You could get every Democrat in California so excited that they all voted twice and it would make not the slightest difference to the outcome of the election. All that matters is getting voters in Michigan who have become uncomfortable and disenchanted with Donald Trump to vote for you once.

Sometimes the best Democrats can do is neutralize “soft” Republican voters to the point where they stay home on election day. Truax believes this presidential election is not one of those times. Try to get moderates, including some Repubicans, to vote for the Democrat, he argues:

The people you really have to motivate aren’t the Democratic base, they’re the people in the middle who have been unsettled by Trump’s presidency. They can see what Trump is and will happily vote for a reasonable alternative. But if Democrats offer what appears to them as a choice between death by hanging and death by firing squad, a lot of them will just give up and not vote at all.

Truax also has a warning for Dems, echoing some of the points made by Ruy Teixeira’s opinion data analysis at TDS in recent months:

Democrats could, however, easily expand this four-state map — for the Republicans. Want to put Minnesota, Colorado, Nevada and New Hampshire in play? Easy. Just run on policies like eliminating private health insurance, reparations for slavery, legalizing drugs and decriminalizing prostitution. Every one of these projects has been pushed by one or more Democratic presidential candidates. There may be things to be said for all of these issues. And someday, we should have a serious policy debate about them. Today is not that day.

Those legendary soccer moms are still out there and, by and large, they have had enough of Trump’s antics. But if you want to run on far-left positions like, say, resurrecting forced busing, they’re going to stick with the devil they know rather than vote for someone who promises to do things like send their kids on 30-mile bus rides every day.

I would add that America surely does need a serious discussion about slavery reparations, which is morally-justified. But the best time to address that issue with real reforms is after a Democratic landslide, when we can actually do something about it. Legalizing marijuana is already happening at the state level. I’m not sure what polls indicate about public sentiment for decriminalizing prostitution, but jailing women who turn to it out of economic hardship is also wrong. Eliminating private health insurance? Don’t even go there. Just make a public option so attractive that private insurance will gradually fade away, as a result of individual choices.

Not all policy-discussions are toxic, as Truax explains. “This doesn’t mean Democrats can’t run on progressive policies. Talk about fixing and expanding Obamacare, if you want. Talk about universal pre-kindergarten. Talk about guaranteed parental leave. If it’s OK with those voters in Erie, it’s OK with me.”

In a summary paragraph, Truax writes,

Democrats have one job in 2020: Beating Donald Trump. Nothing else matters. If progressives manage to mess this up by insisting on hard-left positions and ideological purity, they will own Trump’s second term. There is a time and a place for everything. When the ship is sinking and you find yourself in a lifeboat, you don’t argue about where you want to go, you head for the nearest land. Further travel arrangements can wait until you’re back in civilization.

My quibble with this is that something else does matter, besides “beating Donald Trump.” And that is winning a Senate majority. Dems have a real opportunity to win a landslide in 2020, the kind that can produce a governing majority, which can actually pass major social and economic reforms. That goal is highly compatible with “job one.” Trump fatigue is both wide and deep. If Dems play a good hand, they can win both prizes, plus take back some state legislative majorities and governorships.

A message from Ed Kilgore:

As much as we all like to look at national polls and other public opinion data looking forward to the high-stakes presidential election of 2020, it’s important to keep in mind that under our current system it’s really all about winning 270 Electoral Votes. To keep us focused on that ultimate prize, our friend Taegard Goddard has passed along his new and cool interactive 2020 map, complete with history and other essential information about the Electoral College.

The following article by Ruy Teixeira, author of The Optimistic Leftist and other works of political analysis, is cross-posted from his blog:

Looking forward to 2020, Democrats have a lot of very important questions that can reasonably be debated, from the specific candidate to nominate to which issues to emphasize to the best campaign tactics. But there is a need for political common sense to undergird these debates. If polling, trend data, campaign history and/or electoral arithmetic make clear that certain approaches are minimum requirements for success, they should be front-loaded into the discussion. That way discussion can focus on what is truly important instead of endlessly relitigating questions that are essentially settled.

In other words, start with common sense and then build from there. There will still be plenty of room for debates between left and right in the party, but matters of common sense should be neither left nor right. They are simply what is and what anyone’s strategy, whatever their political leanings, must take into account.

Let’s call practitioners of this approach “Common Sense Democrats”. Here are 7 propositions Common Sense Democrats should agree on.

1. Of course, Democrats need to reach persuadable white working class voters. There is abundant evidence that such voters exist, that they were particularly important in the 2018 elections, that such voters have serious reservations about Trump and that they are central to a winning electoral coalition in Rustbelt states like Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Shifts among such voters do not have to be large to be effective.

2. Of course, Democrats need to target the Rustbelt. Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin were the closest states in 2016, gave the Democrats big bounceback victories in 2018 and, of states Clinton did not win in 2016 currently give Trump the lowest approval ratings.

3. Of course, Democrats need to promote as high turnout as possible among supportive constituencies like nonwhites and younger voters. But evidence indicates that high turnout is not a panacea and cannot be substituted for persuasion efforts.

4. Of course, Democrats need to compete strongly in southern and southwestern swing states like Arizona, Florida, Georgia and North Carolina. Recent election results, trend data and Trump approval ratings all indicate that these states are accessible to Democrats though less so than the key Rustbelt states. As such, they form a necessary complement to Rustbelt efforts but not a substitute.

5. Of course, Democrats need to run on more than denouncing Trump and Trump’s racism. One lesson of the 2016 campaign is that it is not enough to “call out’ Trump for having detestable views. That did not work then and it is not likely to work now. Democrats’ 2018 successes were based on far more than that, effectively employing issue contrasts that disadvantaged the GOP. Trump will be happy to have a unending conversation about “the squad” and those who denounce his denunciations. Don’t let him.

6. Of course, Democrats should not run against Trump with positions that are unambiguously unpopular. These include, but are not limited to, abolishing ICE, reparations, abolishing private health insurance and decriminalizing the border. Whatever merits such ideas may have as policy–and these are generally debatable–there is strong evidence that they are quite unpopular with most voters and therefore will operate as a drag on the Democratic nominee.

7. Of course, Democrats should focus on what will maximize their probability of beating Trump. By this I mean there are plenty of strategies that have some chance of beating Trump–if such and such happens, if such and such goes right. You can always tell a story. But the important thing is: what maximizes your chance of victory, given what we know about political trends and the current state of public opinion. In this election, we can afford nothing less.

Common Sense Democrats. Go forth and multiply.

For an in-depth analysis and better understanding of political demographics and regional trends in presidential politics in Pennsylvania, check out FiveThirtyEight’s audio “Politics Podcast: Who’s Going To Win Pennsylvania In 2020? Citing the “Comey effect” and the lack of good late polling in PA contributing to the surprise outcome of Trump’s PA win in 2016, G. Terry McDonough, director of the Franklin and Marshall College Poll, shares his take on Trump’s prospects for winning the state’s electoral votes again: “Heres the key. Will Trump’s base — they will be with him — but will they be as excited about it and will the turnout be as large as it was in 2016 to offset what is probably going to be a bigger loss in the suburbs than existed before?…Trump’s polling is weaker in Pennsylvania than it is nationally…The Democrats can win the state by focusing on the four Philadelphia suburban counties, the city of Philadelphia, Allegheny County – Pittsburgh – and its suburbs and a couple of counties up in the Lehigh valley…and they always carry Centre County.”

At Dissent, Harold Meyerson notes in his article, “Beyond the Backlash” that “only the white segment of the abandoned working class has responded by moving right. One of the factors behind that movement—a historic factor that the authors don’t consider—is deunionization. Exit polls of presidential elections going back to the late 1960s have generally shown that the margin by which union members vote for the Democrat exceeds that of non-members by roughly 9 percentage points. For white male union members, however, that margin swells to 20 percentage points when compared to their non-union counterparts. Viewed through this prism, the shift of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin into the Republican column in 2016 becomes a bit less mysterious: these are all states where levels of unionization have shrunk from postwar heights of close to 40 percent to current depths near single digits. And while deunionization hasn’t driven African Americans to the right, it has almost certainly reduced their turnout—also a factor in Trump’s victory in once-industrial heartland states.”

At CNN Politics Harry Enten shares some thoughts on the role of Wisconsin in the 2020 presidential election: “The potential problem for the Democratic candidate lies in Wisconsin. Trump’s net approval in that state was -4 points in the 2018 exit polls. That was 5 points higher than it was nationally. Taking into account uncontested races, the Democratic House candidates cumulatively won the House vote by 4 points less in Wisconsin than they did nationally…In other words, the potentially pivotal state in the electoral college may be 4 to 5 points more Republican than the nation as a whole in 2020. This means the opportunity for an electoral college/popular vote split in Trump’s favor remains quite plausible…Still, Trump would lose Wisconsin and the presidential election if the same people came out and voted for the same party in 2020 as they did in 2018.”

Share Blue’s Dan Desai Martin reports that “New poll shows Trump losing Georgia and North Carolina in 2020,” and observes: “Trump’s monumental unpopularity is threatening his reelection chances in two red states in the deep south: Georgia and North Carolina. A PPP poll released Friday shows Trump losing both states to a generic Democrat…In Georgia, Trump trails 50%-46%, while his numbers in North Carolina are slightly worse, trailing 49%-44%…In their analysis, the pollsters note that chatter about how the Democrats could with the 2020 general election has centered on a handful of Midwestern states — Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin — but these new polls “show a possible backup plan to victory in the South as well.”…The same poll showed more voters in both states disapproving of Trump’s job performance than approving of it. In Georgia, Trump was underwater by a 45%-49% gap, and in North Carolina, 46% approve of Trump while 49% disapprove.”

From Michael Tomasky’s “The Southern Strategy Is Back, With a Vengeance. Here’s How Democrats Beat It. This can’t be Trump vs. the Squad. It’s got to be Trump vs. the unified Democratic Party” at The Daily Beast: “The President of the United States is a racist. And the Democrats need to make it an issue. They need to attack him as a racist. They need to nail every Republican to the wall. They need to make this an issue in 2020. If they don’t play hardball here, they will lose…Trump’s ploy is obvious. He wants to make this about AOC, Omar, Pressley, and Tlaib. Make them the face of the Democratic Party, and make people believe they’re “communists,” as both he and Lindsey Graham said Monday, echoing some of the most disgusting demagoguery this country has ever known…That’s what Trump wants. And if the Democrats don’t answer it, they will lose. If they leave it to the Squad to defend themselves, as they gamely attempted to do Monday evening, not only will the four of them be ostracized—but Democrats, the whole party, will lose. This can’t just be Donald Trump vs. The Squad. It has to be Donald Trump vs. the entire unified Democratic Party, and it can’t be about the four of them, it has to be about him.”

“Top Democrats have revealed how they plan to interview special counsel Robert Mueller when he testifies before the House Judiciary and Intelligence Committees this week,” Riley Beggin writes in “What Democrats Want from Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s Upcomming Testimony” at Vox. “Their ultimate goal: To make Mueller’s 448-page report on Donald Trump’s ties with Russia and potential obstruction of justice vivid and interesting to the American people…House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff said Sunday on Face the Nation that doing so is important because most Americans haven’t read Mueller’s summary of his two-year-long investigation…Schiff called the report “a pretty damning set of facts that involve a presidential campaign in a close race welcoming help from a hostile foreign power,” but admitted it is “a pretty dry prosecutorial work product.”…“Who better to bring them to life than the man who did the investigation himself?” Schiff asked…Only 3 percent of Americans have read all of the Mueller report and only 10 percent have read some of it, according to a CNN poll released in May…After Mueller spoke briefly in May, the percentage of Americans who supported beginning impeachment proceedings went from 16 percent to 22 percent, according to an NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll.”

Some “key points” from “2020 Redistricting: An Early Look: GOP retains edge, but perhaps not as sharp of one as it had following 2010” by Kyle Kondik at Sabato’s Crystal Ball: “The Supreme Court’s recent decision to stay out of adjudicating gerrymandering doesn’t necessarily change anything because the court had never put limits on partisan redistricting in the first place…Republicans are still slated to control the drawing of many more districts than Democrats following the 2020 census, although there are reasons to believe their power will not be as great as it was following the last census…How aggressively majority parties in a number of small-to-medium-sized states target incumbents of the minority party following 2020 may help tell us whether the Supreme Court’s decision will lead to more aggressive gerrymanders.”

In her Truthdig article, “Elizabeth Warren Is Putting the Consultant Class on Notice,” Ilana Novick explains that “There’s no outside polling firm or plans to marshal resources for a massive television ad campaign. In fact, campaign staff tells Politico that “it is shunning the typical model for producing campaign ads, in which outside firms are hired and paid often hefty commissions for their work. Instead, Warren’s campaign is producing TV, digital and other media content itself, as well as placing its digital ad buys internally.”…This approach, Politico reporter Alex Thompson explains, “is a rebuke of the consultant-heavy model of campaigns — an often lucrative arrangement in which the people advising campaigns invariably tell candidates that the best political strategy is to buy what they sell, namely TV ads and polling.”…According to Thompson, the ascension of Rospars to chief campaign strategist also “signals that the campaign is prioritizing smartphones and computers over TV.”…If Warren makes it to the general election, Thompson writes, “a large swath of Democratic consultants, including some whom Warren has used in past campaigns, could be relegated to the sidelines.”

At Tapped: The Prospect Group Blog, Katie Malone advises Dems on Building the Right Narrative to Win the Next Recession, and urges, “Before the next recession hits, Democrats need to outline a persuasive narrative to spur large-scale investment. Romer admits that the administration should have done more to make the case in favor of fiscal stimulus to the American public. But since then, the American public has seemingly grown skeptical of much-needed interventions. As Romer told EPI, “Even actions like extending unemployment insurance during a long downturn are now highly controversial.”…Part of the reason for misguided public attitudes, experts lament, is the failure of Democrats to shape the debate. Margarida Jorge, a grassroots organizing expert and executive director of Health Care for America Now, commented on how easy it is for Republicans to monopolize the conversation about the economy when Democrats remain silent about the issue. “When you have nothing to say and your opposition has a lot to say,” Jorge said, “people tend to believe your opposition…Crafting the right narrative about defending workers, reining in Wall Street, and strengthening the social safety net is the first step to drafting adequate policy.”

It’s pretty generally recognized that four 2020 Democratic presidential candidates have separated themselves from the rest of the field. But not many observers are teasing out the implications if it continues, as I tried to do this week at New York:

[L]ess than a year before Democrats meet in Milwaukee to nominate a presidential candidate, the field’s two old white men have lost a significant amount of support, while two women (Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris) have gained significant strength. While everyone understands that Warren and Harris represent a threat to Biden and Sanders, it’s underappreciated how much all four candidates are now separated from the rest of the field.

Using the RealClearPolitics national polling averages as a yardstick, as recently as two months ago, Biden was at 38 percent and Sanders at 19 percent, with Warren, Harris, and Buttigieg clustered in the high single digits; O’Rourke and Booker were a few points behind them; and everyone else was struggling for oxygen. Now Biden (28 percent), Sanders (15 percent), Warren (ditto), and Harris (13 percent) are more closely bunched, with Buttigieg the next in sight at 5 percent. After a boffo second quarter in fundraising, Mayor Pete may have the resources to lift himself from the madding crowd the way Warren and Harris have done. And some other current bottom-feeder could rocket into contention with a big-time performance in the July 30 and 31 debates in Detroit (after that, the heightened requirements for participation in two rounds of autumn debates are likely to serve as an abattoir for struggling candidacies).

And as noted, there are scenarios under which each of these four candidates could put it all away early. Most obviously, despite his recent loss of support nationally, Biden remains in the lead in all four of the early states that vote in February. If he wins them all, he’d be extremely hard to stop. Sanders has one of the more consistent bases of support in the key early states, is showing signs of addressing his minority-voting weakness from 2016, and has plenty of money, so he could plausibly win Iowa and New Hampshire and roar into Super Tuesday with a head of steam. Warren has what is generally conceded to be the best Iowa organization, is rising rapidly in New Hampshire, and can compete with both Sanders and Biden in harvesting good will among a national constituency of admirers. And Harris, building on her first-debate success, has a very plausible Obama-esque strategy of wrecking Biden in South Carolina among the black voters he heavily relies upon, and then forging into front-runner status with a big win in her native California just a few days later.

But if all of these candidates fall just a bit short of their most ambitious goals, and fail to land the knockout punch when they need it, then we could be looking at a truly protracted battle in which no one rival has an indomitable advantage. That does not necessarily mean a contested convention would occur: candidates could try to achieve some breakthrough via unconventional coalitions, alliances among themselves, or early running-mate announcements (tried unsuccessfully by Republicans Ronald Reagan in 1976 and Ted Cruz in 2016, but still worth considering). Democrats do not strictly require pledged delegates to stick with their original candidates (particularly if that candidate has withdrawn), so things could change before delegates arrive in Milwaukee. And then, yes, a gridlocked convention could turn to suddenly re-enfranchised superdelegates, all 764 of them, to help make a decision after the first ballot ends.

If nobody’s made a big move by early March, it’s time to start thinking seriously about these wild convention scenarios — and about which candidate might best unify the Donkey Party. By this time next year, the fear of letting Trump win again will be so palpable that you will be able to weigh it on scales and grill it up for an anxious meal.

The following article by Ruy Teixeira, author of The Optimistic Leftist and other works of political analysis, is cross-posted from his blog:

He is still the incumbent and the economy is still pretty good. So those are advantages. But I think the biggest problem for the Democrats is that they may not run a very smart campaign. In fact, it seems a distinct possibility that they will run a dumb one. Martin Longman at the Washington Monthly points this out in a good piece that echoes some of my arguments and adds some interesting observations concerning the two parties’ coalitions:

“The Democrats have basically substituted their farmer/labor alliance for an urban/suburban one, and it may work out as a nearly even trade in the raw numbers but it has exacerbated the problem of having most of their votes concentrated into small areas while also creating an Electoral College challenge (see 2016).

The flip side of the Republicans losing all their moderates is that the Democrats are now living in a bubble. What they see as obvious is not obvious in most congressional districts. What they see as virtuous is not necessarily seen as virtuous, patriotic, or even sane in most congressional districts.

They are creating two problems for themselves. The first is a possible repeat of 2016, where they become perceived as so out of touch with the values and concerns of small-town and rural Americans that even a ridiculous man like Donald Trump seems highly preferable. The second is that they’re beginning to stress their suburban support with some of their policies, and the only way to offset rural losses is to do even better in the suburbs than they did four years ago. If Trump does as well or even better in his base areas than he did in 2016, and the Democrats do not improve on their suburban numbers, then the president will almost surely be reelected….

[Trump] does have a strategy and the strategy is correctly calibrated for the task at hand. He must racialize the electorate to maximize his vote in heavily-white communities and tap a wedge in between the urban and suburban Democrats so that the latter will defect in sufficient numbers for him to recover his losses. His problem is that efforts to maximize his white vote actually have the effect of pushing urban and suburban Democrats into a closer alliance. For this reason, he will fail unless the Democrats help ramp up his base numbers and depress their own.This is where policies like free health care for undocumented people or abolishing all private health insurance are going to do damage. These things are not popular in general and are especially unpopular with the Democrats’ suburban base. A lot of the Democrats’ rhetoric on border issues is toxic not just in the sticks but also in the communities ringing our cities.

So, yes, the Democrats really could blow this election by running a non-strategic campaign based on abstract values against a campaign that is laser-focused on just the voters it needs to win.

This isn’t an argument for changing values, but it is an argument for not being too stupid to beat a man like Donald Trump.”

This is all well-put and, like the prospect of a hanging, should concentrate the mind. I should add that Longman does not say he thinks Trump is likely to pull this off–merely that it is a distinct possibility given how most Democratic candidates are currently handling themselves.

I continue to hope for an outbreak of political common sense. Don’t let Biden–a flawed candidate to be sure–have this “lane” all to himself!

The following article by Ruy Teixeira, author of The Optimistic Leftist and other works of political analysis, is cross-posted from his blog:

I thought this was a very interesting essay from Sheri Berman on the Social Europe site. While her essay is focused on Europe I think there are some very clear lessons here for the left in the United States.

“Rather than rising numbers of immigrants or increasingly negative attitudes towards them, what seems to contribute most to populism’s success is the centrality of immigration to political competition. During much of the postwar period, political competition in Europe pivoted primarily around economic issues, and so voters who had conservative social views (for example, many members of the working class) didn’t vote on the basis of them. Over recent decades, however, political competition has increasingly focused on social issues such as immigration and national identity, leading voters to be more likely to vote on that basis.

When concerns about immigration are at the forefront of debate—in political-science terms, when immigration’s salience is high—the populist right benefits. This is because in most European countries right-populist parties now ‘own’ this issue: they are most associated with it and their voters are united in their views about it (whereas the left’s voting constituency is divided between social conservatives and social progressives). That populists benefit when the salience of social issues such as immigration is high explains why they spend so much time trying to keep such issues at the forefront of debate: demonising immigrants, spreading ‘fake news‘ about them and so on….

Parties succeed when the issues on which they have an advantage are at the forefront of debate: populists do well when attention is focused on immigration, green parties do well when attention is focused on the environment and social-democratic parties do well when attention is focused on economic issues and, in particular, on the downsides of capitalism and unregulated markets—assuming they have something distinctive and attractive to offer on the economic front. (This has not been the case for many social-democratic parties for too long but many authors at Social Europe are trying to rectify that.)

What the Danish elections should remind us is that politics is largely a struggle over agenda-setting. Defeating populism requires removing the issues on which populism thrives from the forefront of debate. But for the social-democratic left to succeed, it must do more than neutralise the fears populists exploit. It must also focus attention on the myriad economic problems facing our societies—and convince voters it has the best solutions to them.”

Food for thought.

Since the 2020 presidential election is looking to be wild and wooly and passionate, it’s important that Democrats are clear-eyed about the implications of abandoning swing voter persuasion altogether in the pursuit of base mobilization. I wrote about that this week at New York:

Of all the reasons Trump defeated Hillary Clinton in 2016, the most compelling (to me, at least) is that he sprang the upset because an awful lot of voters who didn’t really want the mogul to become president stayed home, voted for a minor-party candidate or even cast a “protest vote” for Trump on the theory that he could not possibly win. From that sound hypothesis has grown the somewhat more dubious postulate that in 2020, if turnout is high, the 45th president is toast. Part of the reason people instinctively believe this is that there are more Democratic than Republicans out there; in other words, an energized Democratic base is going to be larger than its GOP counterpart. But the more tangible rationale is probably a lot simpler: 2018 was a very high-turnout midterm, in which Democrats did well. So if turnout stays high, the donkeys will again romp, right?

Well, that’s plausible, but hardly a lead-pipe cinch, in part because 2018’s high turnout was in fact skewed positively toward Democrats, which may or may not happen again. Historically (and particularly in the previous two midterms in 2010 and 2014), midterm turnout patterns strongly favored Republicans because the older and whiter voters who leaned GOP were since time immemorial more likely to show up for non-presidential elections. In 2018, though, that pattern was turned on its head, as Louis Jacobson recently explained at the Cook Political Report:

“In four states (Idaho, Kansas, Oklahoma, and South Dakota) Democratic gubernatorial vote totals in 2018 were more than 10 percent higher than the party’s showing in the presidential year of 2016. In six more, vote totals increased, but by less than 10 percent (Alaska, Colorado, Georgia, Minnesota, Nebraska, and New Mexico). And in 11 other states, Democratic votes for governor dropped by less than 10 percent from presidential levels (Alabama, Hawaii, Iowa, Michigan, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming) …

“In three states, gubernatorial votes for the GOP nominee increased over Trump’s total by more than 10 percent (Maryland, Massachusetts, and Vermont). In four others, GOP votes increased but by less than 10 percent (Arizona, California, Hawaii and Oregon). And in five states, GOP candidates dropped from presidential-year vote totals by less than 10 percent (Connecticut, Georgia, New Mexico, Texas, and Wisconsin).

“All told, then, Republicans saw gains or modest losses in 2018 in 12 states. However, the strongest showings came in blue states where the party had broken with the Trump-era pattern by running a moderate candidate with crossover appeal. Subtracting those states leaves about nine states in which the GOP gubernatorial nominee overperformed Trump or didn’t see a big fall-off.”

The partisan gap in extremely high midterm turnout was even more notable, Jacobson found, in Senate races. In the most similar recent midterm, moreover, that in 2010, neither party beat presidential turnout levels in more than a few states.

So if Democrats can match those patterns in 2020, victory should be relatively easy. But another way to look at it is that Republicans may have a larger pool of presidential voters who stayed home in 2018 than do Democrats, which is unusual but hardly impossible. That is essentially what Nate Cohn found in a new analysis of what a high-turnout presidential election in 2020 might look like:

“The voters who turned out in 2016, but stayed home in 2018, were relatively favorable to Mr. Trump, and they’re presumably more likely to join the electorate than those who turned out in neither election. In a high-turnout election, these Trump supporters could turn out at a higher rate than the more Democratic group of voters who didn’t vote in either election, potentially shifting the electorate toward the president.”

Perhaps these midterm stay-at-homes are now alienated from Trump, and will either stay home again or flip to the Democratic candidate. But it’s not a sure thing, particularly if you look at the Electoral College map:

“The danger for Democrats is that higher turnout would do little to help them in the Electoral College if it did not improve their position in the crucial Midwestern battlegrounds. Higher turnout could even help the president there, where an outsize number of white working-class voters who back the president stayed home in 2018, potentially creating a larger split between the national vote and the Electoral College in 2020 than in 2016.”

The arguments over the identity of marginal voters and nonvoters could lead in various directions. But the one inescapable conclusion is that driving turnout upward by making the 2020 election a frenzied test of comparative “enthusiasm” is a dangerous game for Democrats, if it’s not supplemented by (1) a least some “swing voter” strategy, and (2) quieter turnout measures (e.g., voter registration drives, data-driven voter-targeting messages, or even traditional knock-and-drag GOTV efforts) that don’t run the risk of riling up both sides equally.

It’s certainly safe to say that Trump and his party are risking disaster by making every presidential utterance an outrage that at best excites his base as much as it infuriates Democrats. And since time immemorial, ideologues on both the left and the right have asserted as a matter of quasi-religious faith that some hidden majority favor their prescriptions, with tens of millions of citizens refusing to vote because the radicalism they crave has been withheld by Establishment centrists. In 2020, though, the stakes are higher than ever if Democrats are wrong about relying on the intensity of voter enthusiasm. It would be smart for them to have a backup plan.

How are Trump’s recent comments urging the congresswomen of ‘the squad” to go back to where they came from polling? At Daily Kos, Hunter explains that “Two thirds of Americans call Trump’s racist tweets ‘offensive;’ a majority call them ‘un-American’“. Hunter notes that “The American public, aside from Republican members of Congress, isn’t going to take nonsense on this one. In a new USA TODAY/Ipsos poll, Americans are calling Donald Trump’s racist weekend tweets “offensive.” And in a result Trump and his allies might be more pointedly concerned about, 59% of Americans are calling Trump’s racist tweets “un-American.”…That is not to say that a majority of self-identified Republicans aren’t standing by Trump. After all, 57% say they agree with Trump’s tweet for his targeted non-white, American-citizen congresswomen to “go back” to their “original” countries. But those Trump allies are overwhelmed by widespread public revulsion by Democrats and independents. Women, in particular, found the tweets offensive by a three-fourths majority…The poll underscores, yet again, just how far the Republican base has drifted from the rest of America’s beliefs and morality.”

With respect to the same poll, Catherine Kim notes at Vox that “A new poll indicates why GOP members are reluctant to chastise the president. Although a USA Today/Ipsos poll found that a majority of people, 68 percent, saw Trump’s tweets as offensive, there was a stark partisan divide: 93 percent of Democrats and 68 percent of independents found the tweet offensive, while only 37 percent of Republicans did, according to the poll, which was released on Wednesday…Only 45 percent of Republicans found telling minorities to “go back where they came from” to be a racist statement, which starkly contrasts with the 85 percent of Democrats who think that way…While 88 percent of Democrats found the president’s tweets “un-American,” only 25 percent of Republicans felt the same way. The difference became more evident when people were asked if it was American to “to point out where America falls short and try to do better.” Fifty-two percent of Republicans found those who criticized American to be un-American, while only 17 percent of Democrats agreed….Following the uproar surrounding Trump’s racist comments, support for the president among Republicans rose by 5 percentage points to 72 percent, according to a Reuters/Ipsos poll released on Tuesday. The same could not be said for his support among other groups: His net approval rating dropped by 2 percent among Democrats…Overall approval of his performance in office remained at 41 percent, while 55 percent disapproved, the same as last week.”

In FiveThirtyEight’s panel discussion, “Will ‘The Squad’ vs. Pelosi Be A Big Problem For Democrats In 2020?,” Perry Bacon, Jr. observes, “My own, non-data judgement, is yes, Democrats would be slightly better off if AOC and her allies were less prominent in the run-up to the 2020 election. Why? Because having issues of race and identity (like immigration policy and four very liberal, female people of color) being central to the presidential election is hard for Democrats. They have become the party of people of color but most voters are white and this is especially true in key swing states (in particular, Michigan and Wisconsin). Also, Trump is likely to run a 2020 campaign about race and identity that raises the question of who should represent America–forcing voters to take sides…Pelosi, I assume, does not want the 2020 election to be seen by the public as a battle between AOC’s vision of America (even if Biden is the Democratic nominee) and Trump’s vision of America. And I think she is right to be concerned about that. This is not a new challenge for Democrats. Hillary Clinton was probably not helped by the rise of Black Lives Matter preceding the 2016 election, and backlash to the civil rights movement arguably helped Richard Nixon win the 1972 election.”

Chris Cillizza explains “Why Trump so badly wants 2020 to be all about socialism” at CNN’s ‘The Point’:”In the Pew poll, which was done earlier this spring, 84% of Republicans and lean Republicans said they have a negative view of socialism. That number included 63% of Republicans who said they has a “strongly” negative view of it…How do you convince those soft(er) Republicans to be for Trump in 2020 despite their misgivings? You find an issue that you can brand the other side with that makes the choice in 2020 between someone you have doubts about and someone that you believe will fundamentally undermine the capitalist system that has, to borrow a phrase, made America great…You getting it now? If the choice in 2020 is between Trump and and a Democrat, he likely loses. If it’s between Trump and a Democrat-who-is-really-a-Socialist, he has a hell of a lot better chance at a 2nd term.”

“If Trump does as well or even better in his base areas than he did in 2016, and the Democrats do not improve on their suburban numbers, then the president will almost surely be reelected,” Martin Longman writes at The Washington Monthly. “This is still not all that likely to happen in my view for the simple reason that Trump has lost support throughout his four years in office. He cannot depend on people to vote for him on the assumption that he’s going to lose anyway. He’s not a (ha, ha) joke or protest candidate anymore. He won’t get the considerable bloc of people who always vote against the incumbent regardless of party. He won’t automatically get the historically anti-Clinton suburban vote either, since there will be no Clinton on the ballot. More than this, Trump has definitely lost support among moderates, particularly well-educated folks from the professional classes. He’s going to do worse with South Asians, East Asians, Latinos, and blacks than he did four years ago. He’s not beginning this race at the starting line with his opponent. Despite the advantages of incumbency, he is starting from the rear…Nixon did not suffer from most of these disadvantages in 1972. He would have been difficult to defeat no matter who the Democrats nominated or what they promised on the campaign trail. Trump is not looking at potentially winning 49 states. He’s looking at trying to win twice while losing the popular vote.”

Nathaniel Rackich brings good news for Dems, also at FiveThirtyEight: “One of the strongest signs of a blue wave in the 2018 election was the green wave that preceded it: Democratic candidates running in that cycle raised googobs of money (a highly technical term). So in addition to indicators like the generic congressional ballot and special election results, the second-quarter fundraising reports filed this week with the Federal Election Commission are another clue as to whether Democratic momentum will carry forward into 2020’s congressional races. And while it’s still early in the election cycle, it looks like fundraising is once again a bullish indicator for Democrats’ success, at least in the Senate…In competitive Senate elections — those that the three major electionhandicappers rate as anything other than solid red or blue1 — Democrats have raised $34.1 million in total contributions in the first six months of 2019, and Republicans have raised $29.3 million…That gap is especially troubling for the GOP because there are eight Republican incumbents running in those 14 races, and incumbents usually raise more money than challengers early on. While Democrats have only four incumbents running, they’ve raised more than four times as much as their Republican challengers in those races. And in the two open-seat races, Democrats are outraising Republicans $1.9 million to $763,771.”

“California Sen. Kamala Harris, former Vice President Joe Biden and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders are in a close race in California, according to a new Quinnipiac poll released Wednesday,” Grace Sparks writes at CNN Politics. “The poll shows Harris at 23%, Biden at 21% and Sanders at 18%. The difference between the candidates’ numbers are within the poll’s margin of error…Beyond the top three, Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren sits at 16%…The race has tightened since a Quinnipiac April survey found Biden, who had not yet formally announced his candidacy, besting the other contenders with 26% of Democratic voters in the Golden State; in that poll, Sanders was at 18%, Harris 17% and Warren 7%…Harris and Warren have both surged since that survey, while Biden has dropped and Sanders has remained steady.”

Oliver Willis notes that “Mitch McConnell is so unpopular only 9% of his campaign cash came from his home state” at shareblue.com. “Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell only received 9% of his reelection campaign donations from his home state of Kentucky, reflecting poorly on his popularity there…The biggest blocks of contributions during the period came from two global financial services firms based in New York: 29 people with Blackstone Group made contributions totaling $95,400; and 14 executives of KKR & Co. are listed as giving a combined $51,000,” the Louisville Courier-Journal reported on Wednesday…”The lack of home state dollars could give potential challengers an opening to criticize McConnell as out of step with the state,” the Center for Responsive Politics, who compiled the embarrassing data on McConnell, noted.”

The stereotype of military veterans as supporters of war takes a big hit in a new Pew Research poll. As Adam Weinstein explains at The New Republic: “The “Long War” that began on September 11, 2001, added to veterans’ already-outsize role in the American narrative. Worship of military service has become an indispensable cog in every politician’s and corporation’s endearment strategy. But on the actual subject of war, almost no one in mainstream politics is actually listening to “the troops.”…That’s the main takeaway from the Pew Research Center’s latest rolling poll of U.S. veterans, published Thursday, in which solid majorities of former troops said the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria were not worth fighting. The gaps between approval and disapproval were not even close to the poll’s 3.9 percent margin of error; barely a third of veterans considered any of those conflicts worthwhile: “Among veterans, 64% say the war in Iraq was not worth fighting considering the costs versus the benefits to the United States, while 33% say it was. The general public’s views are nearly identical: 62% of Americans overall say the Iraq War wasn’t worth it and 32% say it was. Similarly, majorities of both veterans (58%) and the public (59%) say the war in Afghanistan was not worth fighting. About four-in-ten or fewer say it was worth fighting…Veterans who served in either Iraq or Afghanistan are no more supportive of those engagements than those who did not serve in these wars. And views do not differ based on rank or combat experience.” The only meaningful variation pollsters found among vets was by party identification: Republican-identifying veterans were likelier to approve of the wars. But even a majority of those GOP vets now say the wars were not worth waging.”