The following article by Ruy Teixeira, author of The Optimistic Leftist and other works of political analysis, is cross-posted from his blog:

Krysten Sinema: Live Like Her!

Ron Brownstein has a detailed article breaking down the ways in which Biden’s emerging strength among older voters could be crucial to his chances for victory. He quotes some guy named Teixeira in a couple of places:

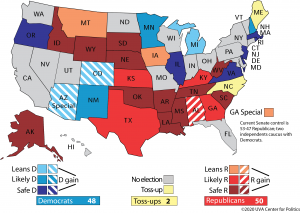

Many Democratic operatives still believe that the party’s long-term future will pivot on its capacity to increase turnout among younger and nonwhite voters, especially in the Sun Belt states growing in population. But that conviction is giving way to a growing awareness that the potential path to victory for Biden, given his own unique strengths and weaknesses, may rely less on that forward-leaning mobilization than on a throwback strategy of reducing Donald Trump’s elevated margins from 2016 among older and blue-collar white voters to the slightly smaller advantages Republicans enjoyed with them 15 or 20 years ago.

“The idea that expanding the map comes down to high mobilization of the constituencies that give you the most support doesn’t necessarily follow,” says Ruy Teixeira, a longtime liberal election analyst and senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. “You can do the same things by reducing your deficits or becoming competitive among groups where you had been doing quite poorly.”…

While some other national polls still show Trump leading with seniors and near-seniors, the general trend line with older voters is more favorable for Biden than it has been for recent Democratic nominees. At the same time, many political professionals in both parties remain uncertain that Biden can excite a large turnout among young people, especially those of color, who rejected him in big numbers during the Democratic primary and have displayed only modest enthusiasm for him in most early general election polls.

“He is not the spark to that flame, for sure,” says Republican strategist David Kochel.

Those trends among the young still concern many Democratic operatives. But a closer look at the demographics of the swing states makes clear that for Biden a strategy centered on appealing to older voters, most of them white, could substitute for mobilizing young people, many of them diverse, in all of the places that both sides consider pivotal in 2020.

“It was never clear to me that the way you expand the map was by enormous turnout among young people,” said Teixeira. “Other moving parts were just as important, if not more important.”

That guy Teixeira may be onto something. But perhaps the most interesting part of Brownstein’s article is where he makes the case the Krysten Sinema’s successful campaign for a Senate seat in Arizona in 2018 could be a model for what Biden’s trying to do.

“Democrat Kyrsten Sinema won a US Senate seat in Arizona that same year by moderating her earlier liberalism and running as a centrist who would build bridges across party lines. Like the other three Sun Belt Democrats, Sinema struggled among older working adults aged 50-64, according to the exit polls; but unlike them she carried a majority of seniors, which helped her squeeze out a narrow victory over Republican Martha McSally. Sinema carried 44% of whites older than 45, a measurable improvement on the other three.

One of the most striking aspects of Sinema’s win was her victory in Maricopa County, centered on Phoenix. Maricopa was the largest county in the US that Trump won in 2016, but Noble’s post-election analyses found that 88 precincts that backed the President in 2016 switched to Sinema two years later. Those included many suburban areas crowded with college-educated voters who broke from Trump nationwide. But when Noble and his team analyzed the Maricopa precincts that moved away from the GOP from 2016 to 2018, he found two retirement communities at the very top of the list: Sun City and Leisure World.

Noble says he believes that those seniors first pulled back from the GOP around its efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act in 2017. His latest statewide poll, which showed Biden leading overall, showed him besting Trump among voters older than 55.

That’s catastrophic for Republicans in Arizona, he notes, since the heavy Latino presence in the younger population reliably tilts it toward the Democrats. (Sinema won three-fifths of voters younger than 45 in 2018.) If Biden can maintain an advantage with those older voters through November, Noble says, “it’s smooth sailing” for him in the state, especially since Trump and the GOP are also eroding among younger college-educated suburbanites.

Sinema’s path, though not as flashy as the approach embodied by Gillum, Abrams and O’Rourke, might be a model for Biden. Polls released over the past week by Fox News likewise found Biden leading with older voters in Pennsylvania and Michigan and tied with them in Florida; a Quinnipiac University survey in Florida showed Trump still leading among older working-age adults but Biden holding a double-digit lead among seniors. An average of all three University of Marquette Law School polls in Wisconsin this year similarly shows Trump trailing by 8 percentage points among voters 60 and older (who broke about evenly in the state last time).”

That’s the Sinema–and now the Biden–formula. And it’s kryptonite to Donald Trump.