Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden will visit Kenosha Wisconsin today. According to Eric Bradner’s CNN Politics report, “Biden and his wife, Jill Biden, “will hold a community meeting in Kenosha to bring together Americans to heal and address the challenges we face,” his campaign said Wednesday…Biden also will meet with Blake’s father, Jacob Blake Sr., and other Blake family members during the visit, according to a family spokesperson and campaign official…The trip comes two days after President Donald Trump visited Kenosha, ignoring the objections of local leaders, including Democratic Gov. Tony Evers, who said in a letter to Trump that he was “concerned your presence will only hinder our healing.”…Biden told reporters Wednesday that he has received “overwhelming requests” from Democratic leaders that he travel to Wisconsin…”What we want to do is — we’ve got to heal. We’ve got to put things together. Bring people together,” Biden said…The shooting of Blake — which left him paralyzed from the waist down, his family says — has moved police brutality, racial injustice and the looting and property damage that have followed some protests to the forefront in one of the nation’s most important swing states in November’s general election.”

Ezra Klein shares some disturbing insights at Vox: “If you had told me, a year ago, that a pandemic virus would overrun the country, that 200,000 Americans would die and case numbers would dwarf Europe, that the economy would go into deep freeze and the federal government prove utterly feckless, I would’ve thought that’s the kind of systemic shock that could crack into public opinion. I’m not saying I would’ve predicted Trump falling to 20 percent, but I would’ve predicted movement…The stability unnerves me because it undermines the basic theory of responsive democracy. If our political divisions cut so deep that even 200,000 deaths and 10.2 percent unemployment and a president musing about bleach injections can’t shake us, then what can? And if the answer is nothing, then that means the crucial form of accountability in American politics has collapsed. Yes, many of us are partisans, with a hard lean one way or the other. But the assumption has long been that beneath that, we are Americans, and we want the country governed with some bare level of competence, that we care more for our safety and our paychecks than our parties.”

Klein also notes, “My view, to be clear, is that Trump’s response to the coronavirus will stand as one of the great governance failures in American history. We are doing far worse than peer nations in controlling case rates and saving lives. Analyses suggest that upward of 70 percent of America’s coronavirus deaths could’ve been prevented by a faster, more capable response along the lines Australia, South Korea, Germany, and Singapore. And to write all this is to still give the White House too much credit — they have largely offered no response at all, shunting this crisis to the states and refusing to release a plan of their own or even follow their own guidelines…Moreover, Trump has, himself, been a model of personal irresponsibility, fueling a culture war over face masks and packing supporters into arenas and the White House lawn. As a result, while 93 percent of Americans who strongly disapprove of Trump say face masks are effective, only 65 percent of those who strongly approve of Trump say the same. It is not, then, simply that Trump has done a poor job managing the federal government’s mobilization. Rather, he has been an active hindrance to the governors and mayors trying to fill the void he’s left.”

But Klein sees some hope for Dems in one key demographic group trend in the largest swing state: “If there is one group Trump is leaking support from, it is older white people in Florida,” says Marc Hetherington, a political scientist at the University of North Carolina. “At least that is how I read the data coming out of Florida. The Covid-19 response is actually killing older people there. As this goes on, more and more of them actually know someone who has been affected in some serious way. According to our data, that appears to have the power to blunt partisanship. Republicans follow their leaders when they are not afraid of getting sick. They don’t follow those cues when they are afraid of getting sick.” Biden now leads by more than 4 points in Florida, up from a dead heat in April.”

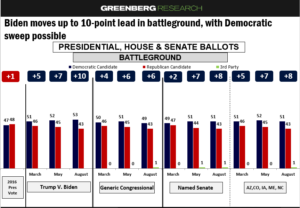

It’s only one poll. But here’s a couple of nuggets from “CNN Poll: Biden’s lead persists post-conventions” by Jennifer Agiesta: “Joe Biden continues to hold a wide advantage among women (57% to 37%), voters ages 65 or older (57% to 40%), people of color (59% to 31%) and White college graduates (56% to 40%). His support among suburban women (56% Biden to 41% Trump) mirrors his lead among women generally, despite the Trump campaign’s focus on shrinking that edge…Men have been a somewhat volatile group in CNN’s surveys in the last few months. As of now, Trump holds 48% support to Biden’s 44%, while in August, Trump held a far wider advantage, 56% to 40%…Trump continues to hold a wide lead among White men (53% to 42% for Biden), and especially White non-college educated men (61% to 33%). White non-college educated women, however, currently break toward Biden (54% to 42%).”

It appears that Republican Sen. Joni Ernst has decided her best chance for re-election is to swig the Kool-Aid. As Joan McCarter reports in “Joni Ernst goes QAnon, suggests Iowa healthcare workers are bilking the system with COVID-19 at Daily Koz: “Maybe Joni Ernst got some backlash from Team Trump for “running on local issues”and trying to avoid the Trump racist conspiracy theory trap. To prove her bizarro bona fides, she decided to go QAnon and accuse Iowa’s medical community of falsifying COVID-19 data for the money…Ernst told a gathering of about 100 supporters that she’s “so skeptical” of the official death count from coronavirus. “They’re thinking there may be 10,000 or less deaths that were actually singularly COVID-19,” Ernst said. “I’m just really curious. It would be interesting to know that.” Uh-huh. “They’re” thinking. They being the whack-job QAnon proponents who’ve found a side-line from Democratic pedophiliac pizza parlors in COVID-19 trutherism. She went even beyond that, though, to skate up to the line of accusing Iowa’s medical community of fraud. “These health care providers and others are reimbursed at a higher rate if COVID is tied to it, so what do you think they’re doing?” she questioned the crowd. That’ll sure boost her standing with Iowa’s front-line medical community, which is right now dealing with the nation’s second-highest rate of virus spread.”

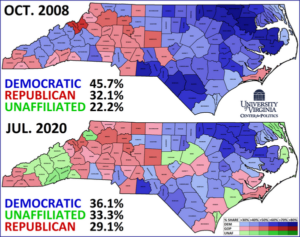

In “States of Play: North Carolina,”This year, the North Carolina contest is one of just three Senate races that the Crystal Ball considers a Toss-up…Overall, no other state appears to have as many important and competitive races this year as does North Carolina. It is the only big state to feature competitive races for president, Senate, and governor. It also has new congressional and state legislative maps, which will allow Democrats to net at least two new U.S. House seats and could threaten GOP majorities in the state legislature.” Further, “After President Obama’s narrow win there in 2008, light red North Carolina has proved elusive for Democrats — but it remains a target for both sides…North Carolina’s politics are increasingly shaped by its growing bloc of unaffiliated voters…Over the past decade, North Carolina’s traditional east-west divide has evolved into more of an urban-rural split — a pattern seen in many other states…In a state known for volatile Senate races, 2020’s contest should be true to form, and further down the ballot, voters will weigh in on several statewide races.”

Coleman and Stillerman provide a map to show how the political demographics of NC is changing:

Here’s a jolly riff from Andy Borowitz’s “Trump Claims That Sleepy Person With No Energy Will Somehow Be Peppy Enough to Destroy Entire Country” at The New Yorker: “Donald Trump claimed on Wednesday that Joe Biden is “incredibly sleepy” and has “zero energy,” yet somehow is peppy enough to destroy life in the United States as we know it…Speaking to Sean Hannity on Fox News, Trump attempted to explain the apparent contradiction between a person being barely sentient yet capable of singlehandedly dismantling a global superpower…“Sleepy Joe is practically unconscious and almost doesn’t have a pulse,” Trump said. “But that’s because he has put his entire body into hibernation, like a bear.”…Trump went on to say that he had seen a documentary about bears on Animal Planet “that was so scary, every voter needs to see it.”…“This bear hibernated all winter, but then, when he woke up, he had enough energy to rip a hiker’s face off,” he said. “Just you watch. Joe Biden is conserving his energy right now, but, as sure as you’re sitting there, the minute he takes office he will rip this country’s face off.”…Trump said that, in November, the American people face a stark choice. “It’s between me, their favorite President, and an angry bear who hasn’t eaten in months,” he said.”