The following article by Ruy Teixeira, author of The Optimistic Leftist and other works of political analysis, is cross-posted from The Wall St. Journal:

We’re still waiting for the final results of the 2022 election. But it’s clear that Democrats decisively beat both expectations and the elections’s “fundamentals”—the incumbent party’s usual midterm losses, President Biden’s low approval rating, high inflation, voter negativity on the economy and the state of the country. Republicans look set to take back the House but only by a modest margin. And the Senate will remain in Democratic hands, albeit narrowly.

The Democrats’ relatively good night is attributable, above all, to their secret weapon: Donald Trump. Mr. Trump’s ability to push Republican voters into picking bad, frequently incompetent candidates with extreme positions on issues from the 2020 election to abortion was a disaster for Republicans.

They know it. Scott Jennings, a former deputy to Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell, tweeted: “How could you look at these results tonight and conclude Trump has any chance of winning a national election in 2024?” Chris Christie, the Republican former New Jersey governor, noted: “We lost in ’18. We lost in ’20. We lost in ’21 in Georgia. And now in ’22 we’re going to net lose governorships. . . . There’s only one person to blame for that, and that’s Donald Trump.” Mike Lawler, a newly elected Republican congressman from New York, suggested the party needed to “move forward” from Mr. Trump.

This rising chorus will create some pressure for change within the GOP. Where might they turn? This election provides an obvious model, which could present a big challenge for Democrats. Call it their Ron DeSantis problem.

In Florida’s gubernatorial election, Mr. DeSantis absolutely crushed his Democratic opponent, Charlie Crist, beating him by 19 points. This landslide included carrying Hispanic voters by 13 points and working-class (noncollege) voters by 27 points. Democrats nationally have been bleeding support from both these voter groups. Since 2018 the Democratic advantage has declined by 18 points among Hispanics, by 17 points among working-class voters and by 23 points among nonwhite working-class voters.

The geographic pattern of results in Florida underscores Mr. DeSantis’s strength. He carried heavily Hispanic Miami-Dade county, historically the Democrats’ firewall, by 11 points. He carried Osceola County by almost 7 points—a county where Puerto Ricans, among the most Democratic of Hispanic subgroups, loom large.

Democrats assumed that Mr. DeSantis’s flying migrants to Martha’s Vineyard would disqualify him among Hispanic voters. Evidently not. They also assumed that his sponsorship of a law prohibiting instruction in gender ideology for K-3 children would hurt him politically. Wrong again.

How does Mr. DeSantis do it? By being a smart, disciplined politician who knows how to pick his fights and has a strong sense of public opinion, particularly working-class opinion. I believe his combination of traits—Mr. Trump’s greatest strength, without his greatest weakness—could give the Democrats fits. He would be able to attack them on crime, immigration, race essentialism, gender ideology, inflation and energy prices without presenting the easy target provided by Mr. Trump and his acolytes’ extreme ideas.

Democrats, truth be told, are now in a weird codependent relationship with Mr. Trump. They know—and they are correct in thinking this—that the craziness associated with him is their most effective point of attack against the Republican Party and its candidates. Mr. Trump, of course, loves being the center of controversy.

But this codependent relationship makes the Democrats lazy. Instead of taking stock of their weaknesses and seeking to overcome them, they go back to the well on the evils of Mr. Trump, his nefarious supporters and their election denialism.

Meanwhile, the weaknesses remain. In a pre-election poll conducted by Impact Research for Third Way, respondents preferred Republicans over Democrats by 18 points on the economy and inflation and by 20 points or more on crime and immigration. The poll also found slightly more voters regarded the Democratic Party as “too extreme” (55%) than felt that way about the Republican Party (54%).

These election results seem unlikely to provoke the kind of introspection Democrats need to correct these vulnerabilities, especially among working-class and Hispanic voters. Mr. Biden, cheered on by the left, has already announced that he will do “nothing” differently. This puts them in an exceptionally poor position to address the DeSantis problem. What if 2024 arrives and they no longer have Donald Trump to kick around?

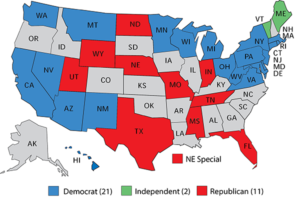

To compound the problem, Democrats are staring down the barrel of an unfavorable Senate map in 2024. Democrats will be defending 23 of the 33 seats in play. Holding those Democratic seats will mean winning in a raft of red and purple states: Arizona, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Wisconsin and West Virginia. The Republican seats that will be up are all in solid GOP states, with the possible exceptions of Texas and Florida (and we saw what just happened there).

Imagine a DeSantis ticket, accompanied by saner, more competent Senate candidates. Are the Democrats prepared for that? I think not. But instead of addressing the problem—or even admitting it exists—they’re counting on Mr. Trump to bail them out. This seems exceptionally foolish. It’s also morally reprehensible: They’re trading a better chance of winning for the possibility that Mr. Trump might become president again.

Mr. Teixeira is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a co-editor of the Liberal Patriot, a Substack newsletter.