The following article by Ruy Teixeira, author of The Optimistic Leftist and other works of political analysis, is cross-posted from his blog:

Can the Democrats Walk Down the Street and Chew Gum at the Same Time?

We shall see. John Cassidy, in a recent New Yorker column, partly based on my research, makes the case that they must do so.

“The Democratic candidate, whoever it is, needs a convincing strategy for winning at least some of the battleground states that Trump carried last time. Failing to focus on this goal relentlessly would be inviting a repeat of 2016.

At least mathematically, the elements of a successful battleground-state strategy are clear. The Democratic candidate needs to excite voters in the Democratic base, particularly minorities and highly educated whites, while also trying to appeal to as many people as possible in Trump’s core demographic, which consists of whites who don’t have a four-year college degree. Contrary to some analyses, both of these things are necessary: it isn’t an either-or choice. The Democrats need a dual strategy….

In 2016, about a third of Hispanics and Asians voted for Trump, according to Teixeira and Halpin’s figures, and so did more than four in ten college-educated whites. Conversely, even as Trump racked up a huge margin among white non-college-educated voters—thirty-two percentage points—almost a third of the people in this category voted for Hillary Clinton.

Regional differences also complicate things. In much of the Midwest, which has long been a key electoral region, non-college-educated whites still constitute a majority of the voters, or close to it. Teixeira and Halpin project that in 2020 this group will make up roughly fifty-six per cent of the eligible electorate in Wisconsin, fifty-two per cent in Michigan, roughly forty-nine per cent in Pennsylvania, and fifty-two per cent in Minnesota, which Trump lost narrowly in 2016 and is targeting again.

Because candidates can’t rely on monolithic voting patterns, they can’t rely on monolithic electoral strategies either. Successful Presidential candidates, even as they target their core supporters, somehow manage to limit their losses among groups that aren’t inherently favorable to them. That is what Barack Obama did in 2012, when he held Mitt Romney’s victory margin among white non-college-educated voters to twenty-two per cent, while racking up big victory margins among minorities and highly educated whites. This two-step garnered him three hundred and thirty-two votes in the Electoral College.

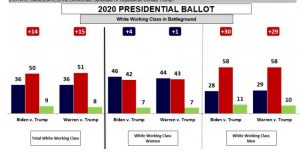

Given Trump’s popularity among working-class whites, and the emphasis that he and his campaign are placing on their vote, it would be very difficult for any Democrat in 2020 to match what Obama did in 2012. But this doesn’t mean that the Democrats should give up on this demographic. Even just preventing Trump from expanding his 2016 margin among non-college-educated whites could be sufficient to deny him a victory in key battleground states, and in the election over all, Teixeira and Halpin argue….

None of this means that the Democrats should limit efforts to mobilize minorities, college graduates, and other Democratic-leaning groups. To the contrary, it is absolutely imperative that they continue, for example, launching enrollment drives in black neighborhoods in Milwaukee and taking steps to cement their 2018 gains in affluent districts north and west of Philadelphia. That is what it means to follow a dual strategy of attacking Trump’s weaknesses and trying to neutralize his strengths.

And paying attention to working-class white voters doesn’t necessarily mean tempering progressive policy proposals like raising taxes on the rich, tackling political corruption, providing universal day care, and guaranteeing health care to everyone….

The fundamental point is that the Democrats need to lay out a policy platform that appeals to a wide range of Americans, regardless of their race, location, and educational background, while also hammering home the message that Trump is divisive, fraudulent, self-dealing, and dangerously erratic. Among white non-college-educated women, if not their male counterparts, there is already some evidence of a willing audience for this narrative….

Even if the Party’s 2020 candidate falls short of drawing even with working-class women, significantly reducing Trump’s advantage among these voters would go a long way toward assuring his defeat. Above anything else, that has to be the goal.”

Yes indeed, that does have to be the goal–which calls for the chewing gum and walking down the street trick. Put more broadly, let me reintroduce my concept of Common Sense Democrats, which I motivate and explain as follows.

Looking forward to 2020, Democrats have a lot of very important questions that can reasonably be debated, from the specific candidate to nominate to which issues to emphasize to the best campaign tactics. But there is a need for political common sense to undergird these debates. If polling, trend data, campaign history and/or electoral arithmetic make clear that certain approaches are minimum requirements for success, they should be front-loaded into the discussion. That way discussion can focus on what is truly important instead of endlessly relitigating questions that are essentially settled.

In other words, start with common sense and then build from there. There will still be plenty of room for debates between left and right in the party, but matters of common sense should be neither left nor right. They are simply what is and what anyone’s strategy, whatever their political leanings, must take into account.

Let’s call practitioners of this approach “Common Sense Democrats”. Here are 7 propositions Common Sense Democrats should agree on.

1. Of course, Democrats need to reach persuadable white working class voters. There is abundant evidence that such voters exist, that they were particularly important in the 2018 elections, that such voters have serious reservations about Trump and that they are central to a winning electoral coalition in Rustbelt states like Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Shifts among such voters do not have to be large to be effective.

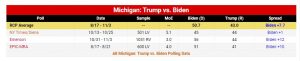

2. Of course, Democrats need to target the Rustbelt. Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin were the closest states in 2016, gave the Democrats big bounceback victories in 2018 and, of states Clinton did not win in 2016, currently give Trump the lowest approval ratings.

3. Of course, Democrats need to promote as high turnout as possible among supportive constituencies like nonwhites and younger voters. But evidence indicates that high turnout is not a panacea and cannot be substituted for persuasion efforts.

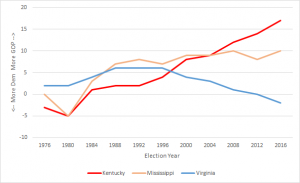

4. Of course, Democrats need to compete strongly in southern and southwestern swing states like Arizona, Florida, Georgia and North Carolina. Recent election results, trend data and Trump approval ratings all indicate that these states are accessible to Democrats though less so than the key Rustbelt states. As such, they form a necessary complement to Rustbelt efforts but not a substitute.

5. Of course, Democrats need to run on more than denouncing Trump and Trump’s racism. One lesson of the 2016 campaign is that it is not enough to “call out’ Trump for having detestable views. That did not work then and it is not likely to work now. Democrats’ 2018 successes were based on far more than that, effectively employing issue contrasts that disadvantaged the GOP. Trump will be happy to have an unending conversation about those he loves to denounce—criminal immigrants, radical Congresswomen Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, etc–and those who denounce his denunciations. Don’t let him.

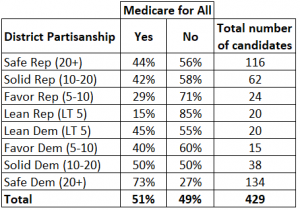

6. Of course, Democrats should not run against Trump with positions that are unambiguously unpopular. These include, but are not limited to, abolishing ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency), reparations for the descendants of slaves, abolishing private health insurance and decriminalizing the border with Mexico. Whatever merits such ideas may have as policy–and these are generally debatable–there is strong evidence that they are quite unpopular with most voters and therefore will operate as a drag on the Democratic nominee.

7. Of course, Democrats should focus on what will maximize their probability of beating Trump. By this I mean there are plenty of strategies that have some chance of beating Trump–if such and such happens, if such and such goes right (cutting-edge progressive positions produce high turnout among Democratic voters but not among Republicans). You can always tell a story. But the important thing is: what maximizes your chance of victory, given what we know about political trends and the current state of public opinion. In this election, Democrats can afford nothing less.