The following article by Ruy Teixeira, author of The Optimistic Leftist and other works of political analysis, is cross-posted from his blog:

I thought Biden had a solid debate, which should help him, as did Klobuchar, which may help her in Iowa, her make-or-break state.

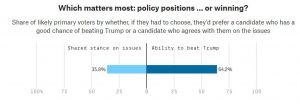

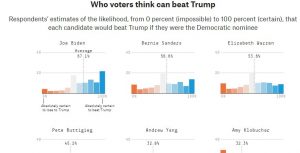

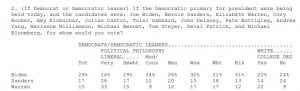

538 released some pre-debate polling and Biden already looked–at least on the national level–to be in very good shape. He had the highest favorability rating of the candidates on stage and had a strong lead on the candidate likely primary voters were at least considering voting for. Likely primary voters also said, by a lopsided 64-36 margin, that they preferred a candidate who had a good chance of beating Trump over a candidate who agree with them on the issues (see graphic below). And Biden had a strong lead over the other candidates on who would be most likely to beat Trump if he or she were the nominee (see graphic below).

Today also saw the release of a lengthy Politico profile by Ryan Lizza on Biden’s advisers. The piece provides useful information on some of the things Biden seems to be getting right about this campaign.

“A year ago, Biden’s retro campaign, with its retro staff and retro view of who Democratic voters are, was predicted to have a swift demise. It didn’t happen. And it if it succeeds in the coming months, Biden and his team will have challenged everything people thought they knew about the Democratic Party in the age of Trump….

Two dominant storylines had emerged from the 2018 midterm elections. In several safe districts, mostly in in urban areas, a number of younger, more left-wing candidates had defeated incumbent Democrats in primaries and then retained the seats for the party in the general election. The most notable example was Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the then 28-year-old former Bernie Sanders campaign volunteer who defeated Joe Crowley, a 20-year incumbent twice her age, in a New York City primary. AOC beat Crowley by 4,100 votes. She now has almost 6 million Twitter followers.

At the same time in 2018, in a number of Republican-held swing districts, moderate Democrats defeated liberal primary opponents and went on to flip the seat for Democrats. Perhaps the best example was Abigail Spanberger, a former CIA officer from Northern Virginia who first beat a progressive challenger in the primary, then defeated Dave Brat, one of the most conservative House Republicans and a Tea Party celebrity.

Both AOC and Spanberger represented a major political disruption, but in the media, and especially on Twitter, which is not used by 78 percent of Americans, AOC came to define the purported direction of the Democratic Party. The issues of the AOC left soon defined the early months of the contest for the Democratic presidential nomination as candidates outbid each other with calls to abolish ICE, decriminalize the border, embrace the most robust version of the Green New Deal and, most of all, support “Medicare for All.”…

Biden had campaigned around the country in 2018. Spanberger was one of his major primary endorsements that year. Not only could he not AOC-ify himself, he was convinced he didn’t need to.

He had what now seems like a profound insight. “Everyone is misreading the electorate,” he told his guest. “I campaigned in swing places, and the candidates who are winning are people who can get the middle.”…

Biden and his longtime advisers, see the moment as calling for a new kind of triangulation, one that co-opts much of the left’s modern agenda, but sands down its most electorally unpopular edges—decriminalizing the border, banning private health insurance, eliminating all college debt—which they see as key to winning over those Democrats who defected or didn’t vote in 2016…..

The campaign developed a three-pronged message: that the election was about the “soul of the nation”; that the threatened middle class was the “backbone of the nation”; and that what was most needed was to “unify the nation.” Only Biden could restore the nation’s soul, repair its backbone, and unify it.

Donilon and Biden loved it. The only problem? A lot of other Biden advisers hated it. It seemed corny and tone-deaf. “Biden was totally in on it at the outset of this campaign and no one else was—no one,” said the adviser. “They said that’s not where people’s heads are at, because obviously there’s a big debate swirling on the left.”

Ignoring the noisy activist left and its megaphone on social media was perhaps the most consequential decision Biden made at the start of the campaign.”

That last sentence tells you a lot about what Biden has gotten right in this campaign. And about how, while he is endlessly derided by many pundits, activists and, yes, people on Twitter, he’s actually got some serious political smarts that some of other candidates seem to lack.