The following article by Ruy Teixeira, author of The Optimistic Leftist and other works of political analysis, is cross-posted from his blog:

Can Sanders Beat Trump?

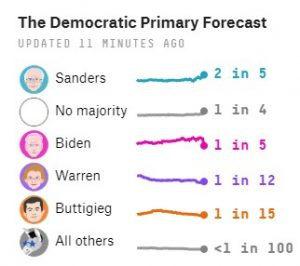

It is certainly possible. But that’s really not the right question. The right question is: how likely is it that Sanders would beat Trump if he were the nominee?

Jon Chait makes this point with admirable clarity in his latest column:

“The truth is we are all clueless about what voters want or will accept,” argues conventional-wisdom-monger Jim VandeHei, in a signal of how deeply the anti-probabilistic fallacy has spread. It is true that there is uncertainty attached to every outcome. The talking heads who guarantee Sanders will lose are wrong — any nominee might win, and in a polarized electorate, both parties have a floor of support that gives even the most toxic candidate a fighting chance. In 2016, Trump was the most unpopular candidate in the history of polling, but he squeaked into office because everything broke just right for him. It could happen for Bernie, too.

But to concede that we cannot be certain about the future does not mean we know nothing. An imperfect comparison might be to predicting the outcome of sporting events. You don’t know the outcome in advance, but it is usually possible to make probabilistic predictions. Those predictions are wrong all the time. But it would be silly to conclude that, just because upsets happen, every game should be treated as a coin flip. A huge amount of pro-Sanders commentary is based on simplistically conflating the correct claim that we lack perfect clarity with the incorrect claim that we have no clarity at all.”

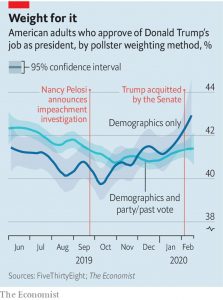

With that in mind, what do we know that might shed light on how Sanders would do against Trump? First, of course, there is the trial heat polling. That polling, according to RCP averages, has Sanders and Biden running ahead of Trump nationally by essentially identical amounts and both ahead of other tested Democratic candidates.

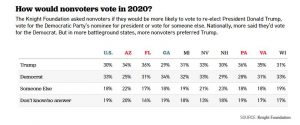

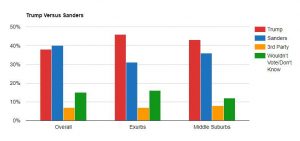

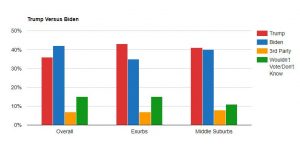

The same pattern with Biden and Sanders relative to the other Democratic candidates can be seen in swing state polling, with the difference that Biden generally generally runs a little bit better than Sanders in most swing states. You can see this both in the RCP trial heat averages and in preliminary state-level breakdowns of the Voter Study Group Nationscape survey (more than 170,000 interviews so far, 6000 nespondents per week)

This suggests that both Sanders and Biden, neither of whom has name recognition problems, are currently capturing anti-Trump, pro-Democratic preferences fairly efficiently. Put another way, simply hearing their names and knowing who they are, does not, at this point, deter large numbers of respondents from expressing pro-Democratic sentiments.

But in a general election campaign, of course, the Trump campaign will be working strenuously to sow doubts about the Democratic candidate and convince undecided voters and those with soft Democratic preferences that Trump, whatever objections such voters may have to him, is by far the lesser evil when compared to the Democrat. This is where Sanders will run into trouble, since since he is poorly set up to parry such attacks among persuadable voters.

David Leonhardt summarizes his problem succinctly:

“[Sanders] has taken a nearly maximalist liberal position on every major issue. It’s especially striking from him, because he has shown over his career that he grasps the importance of building a coalition.

Sanders once won over blue-collar Vermonters with help from a moderate position on guns. “We need a sensible debate about gun control which overcomes the cultural divide that exists in this country,” he said in 2015, “and I think I can play an important role in this.” He was also once an heir to organized labor’s skepticism of large-scale immigration. “At a time when the middle class is shrinking, the last thing we need is to bring over in a period of years, millions of people into this country who are prepared to lower wages for American workers,” he said in 2007.

Now, though, Sanders has evidently decided that progressives will no longer accept impurities — or even much tactical vagueness. He, along with Elizabeth Warren, has embraced policies that are popular on the left and nowhere else: a ban on fracking; the decriminalization of border crossings; the provision of federal health benefits to undocumented immigrants; the elimination of private health insurance.

For many progressives, each of these issues has become a moral litmus test. Any restriction of immigration is considered a denial of human rights. Any compromise on guns or health care is an acceptance of preventable deaths.

And I understand the progressive arguments on these issues. But turning every compromise into an existential moral failing is not a smart way to practice politics. It comforts the persuaded while alienating the persuadable.

F.D.R. and Reagan understood this, as did Abraham Lincoln and many great social reformers, including Frederick Douglass, Jane Addams, Martin Luther King Jr. and Cesar Chavez. Strong political movements can accept impurity on individual issues in the service of a larger goal: winning.”

That’s the nub of his problem right there. He really is extremely vulnerable to brutal attacks from his Republican opponent, which will require unusual deftness and savvy to counter successfully. So far, we haven’t seen a Sanders who seems capable of doing that.

Of course, Sanders does have a response to the potential difficulty summarized here: turnout, turnout, turnout! But as I and others have shown, this is a chimera. If Sanders is to beat Trump, he’ll have to it the old-fashioned way: convincing many voters who don’t adore him that he is indeed a superior choice when compared to Trump.

Who are these voters? Some clues may be found a recent piece by Patrick Ruffini based on Nationscape data. Ruffini finds that while both Biden and Sanders have solid leads over Trump in the national data, their coalitions are not identical. Specifically, Sanders does quite a bit better than Biden among young voters but lags seriously lags behind among voters over 45. And while Sanders is comparably strong among nonwhite voters and lags Biden only slightly among white noncollege voters, he trails Biden’s performance by 8 points among white college voters.

If Sanders is the nominee and wants to maximize his probability of beating Trump, he is going to have to face up to these difficulties. If not, I fear we’re in for a long and painful next four years.