David A Graham explains the “surprising reason” why “White Voters Are Abandoning Trump” at The Atlantic. Staff writer Graham argues that, even more than the pandemic and tanking economy, “the driving factor for Trump’s collapse appears to be race.” Further,

Polls have consistently shown that Americans disapprove of his response to protests of police violence and believe that he has worsened race relations. In the New York Times/Siena poll, race relations (33 percent) and the protests (29 percent) are the only areas where issue approval lags behind his overall vote preference. In the Harvard/Harris poll, the same two areas earn Trump his worst marks of any issue, though they are still slightly higher than his expected vote.”

Voters are right that Trump is worsening race relations and handling the protests poorly. In the past two days alone, the president has retweeted (and then deleted) a video of one of his supporters shouting “White power!” and another of two white supporters pointing guns at black protesters marching past their house…As my colleagues and I have reported, exploiting racial tensions has been a way of life for Trump since the earliest days of his business career, and it was the unifying concept of his 2016 campaign. He has followed that path during his presidency, including his notorious response to a violent white-supremacist march in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017, in which he found “very fine people” on both sides.

Graham says, “What is different this time is the way people are responding”:

But why? Perhaps it’s just a matter of what issues are most important to voters right now. There’s always been a sizable contingent of reluctant or conflicted Trump supporters. In 2016 exit polls, only 35 percent of voters said Trump had the temperament to be president, but he won 46 percent of the popular vote. These voters are a familiar staple of news coverage too—the ones who preface their support with “I don’t always like the way he phrases it” or “I wish he would tone it down a little, but…”

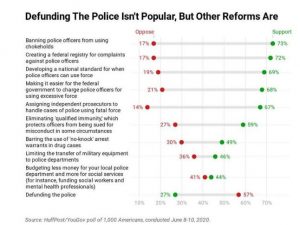

There are apparently a sizable number of voters – nobody knows how many – who are not particularly liberal on racial justice issues, but recognize that Trump has gone out of his way to fan the flames of racial discord to further divide and polarize Americans and needlessly disrupt our society to an unprecedented level. Graham notes that “the profusion of news coverage has made issues of race impossible to ignore,” and:

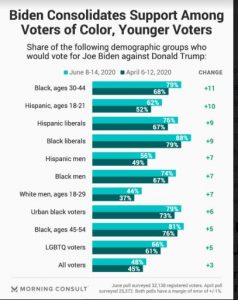

Alternatively, perhaps voters are shifting not just their priorities but their views. As the political scientist Michael Tesler writes, there’s evidence of real shifts in public opinionon race over the past six weeks or so. While views on policing are moving in response to a wide range of incidents, it’s clear that the Floyd case—brutal, senseless, and captured in excruciating clarity on video—has captured white attention in a way other deaths at the hands of police have not. One reason for that may be the coronavirus. Ashley Jardina, a political scientist who studies racial attitudes among white people, told me that she suspects because people are stuck at home due to the pandemic, they’re consuming more news and changing their views on race…

The hardest-core Trump supporters—especially non-college-educated white men—are unlikely to be swayed by the news. They are why Trump’s approval likely has a floor somewhere in the 30s, and why his share in national horse-race polls does too. But if reluctant Trump voters from 2016 are undergoing a change on their view of race relations, it could have seismic implications for his reelection.

Graham doesn’t dispute that former Vice President Biden’s positive image further undermines Trump’s tanking prospects, and notes that, “steady-rolling Joe Biden—creates a contrast that is unflattering for Trump, especially in times of crisis.”

With political preferences hardening and time running out, Graham concludes that “In a new YouGov poll, 94 percent of registered voters said they had already made up their mind about how they’ll vote in November. That gives the president little maneuvering room to regain them and get back in a winning position—especially since there’s not much chance that he’s going to change his own rhetoric or style.”

Put another way, Trump’s racially-driven ‘inflame the base’ strategy has reached its limit in a polarization-weary electorate. His mismanagement of the Covid-19 pandemic and limp response to the declining economy also make a Democratic landslide a growing possibility – if Biden and Democrats play a wise hand for the next 17 weeks.