The good news from South Carolina is that we have a solid Democratic challenger running for Lindsey Graham’s U.S. Senate seat. As Li Zhou reports at Vox: “Jaime Harrison, a former chair of South Carolina’s Democratic Party, is officially challenging Sen. Lindsey Graham in 2020 — and he thinks he can win by swaying some Republicans in the process…As Harrison told the New York Times’s Astead Herndon, he thinks he could build a coalition of Democratic voters and crossover Republicans in order to ultimately secure a victory…“When your health care is threatened or you’re crushed under the weight of student loans, politics doesn’t matter — and character counts,” Harrison said as part of his launch, which included hefty criticism of the incumbent. In a campaign video, he lambasted Graham for sharply changing his stance on Trump. Clips show Graham calling the president a “race-baiting, xenophobic and religious bigot” in 2016, and then turning around and saying the exact opposite after Trump won the election.” Harrison hopes to win support from state voters who are angry about Graham’s complete lack of leadership regarding the closing of rural hospitals, water pollution and student loans.

Despite his incumbency and GOP strength in SC, Graham is burdened by an embarrasing surfeit of video clips revealing his creepy flip-flops on key issues and statements about Trump. Here’s an opening salvo from the Harrison campaign:

Contribute to Harrison’s ActBlue page right here.

Perry Bacon, Jr. presents a case that “The House Probably Has A Pro-Impeachment Majority Right Now” at FiveThirtyEight: “Only a few dozen of the 235 Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives have publicly called for the impeachment of President Trump, or even for Congress to launch a formal impeachment investigation. And that number hasn’t meaningfully changed — so far, at least — even after former Special Counsel Robert Mueller gave a closing public statement Wednesday in which he all but said his investigation concluded that Trump obstructed justice regarding the probe of potential Russian interference in the 2016 election…But the relatively small number of Democrats calling for impeachment doesn’t mean the vast majority of House Democrats oppose impeachment — or, more precisely, that they would vote “no” on impeachment. In fact, it’s likely the overwhelming majority of House Democrats would vote to both the launch of an impeachment inquiry and for impeachment itself if either or both came up for a vote.” Bacon’s estimate is based on a core group of 150 House members in “safe Democratic districts — districts that are blue enough to withstand an impeachment backlash even if it did occur,” plue several other groups, which would likely respond to pro-impeachment momentum.”

Can a presidentail candidacy based more on issues than charisma, comfort zones or identity win the Democratic nomination? That’s a pivotal question being addressed by Elizabeth Warren’s run for the white house, explain Gregory Krieg and Jeff Zeleny in “Elizabeth Warren breaks through crowded 2020 field — with a plan” at CNN Politics. “For five months now, Elizabeth Warren has bounced around the country pitching ambitious ideas — typically anchored by well-timed policy rollouts — to achieve the “big, structural change” at the core of her pitch to Democratic primary voters…Now, with the first round of debates in sight, the energetic campaigner is beginning to see a different kind of movement — in the polls. The latest round of surveys have shown Warren creeping up behind her ideological ally and friend Bernie Sanders, the Vermont senator whose campaign is increasingly adapting similar smallball tactics as a way of more directly addressing voters’ questions and concerns. Former Vice President Joe Biden remains the frontrunner by a comfortable margin, but in the race to represent the party’s more liberal wing, Warren is quietly on the rise.” The authors cite Warren’s “knack for serving up a complicated policy in a digestible bite” and her “I have a plan for that” mantra, which is getting considerable media play.

“Voter Registration Is Surging—So Republicans Want to Criminalize It,” writes Eliza Newlin Carney at The American Prospect. Carney explains that “In the wake of a midterm that saw surging turnout by non-white, young, and urban voters—all blocs that tend to favor Democrats—a backlash in GOP state legislatures was perhaps inevitable. What troubles voting rights advocates is that Republicans have now set out to penalize not just voters but the groups trying to register them, in some cases with astronomical fines and jail time that effectively criminalize civic engagement…The most extreme example is a law newly enacted in Tennessee that imposes civil and criminal penalties, including fines of up to $10,000 or more and close to a year in jail, on organizers who submit incomplete registration forms, fail to participate in state-mandated trainings, or fail to submit forms within a ten-day window. The law violates both the First and the 14th Amendments, say civil rights advocates who have filed suit, and also runs afoul of the National Voter Registration Act.” Carney notes other efforts to suppress voter registraiton campaigns in Arizona, Georgia and Texas.

So, in the wake of Mueller’s warning about the urgency of the continuing threat of Russian interference in our elections, what is being done to protect the integrity of our elections? Very little at the federal level, it turns out, according to Peter Stone’s “Trump not doing enough to thwart Russian 2020 meddling, experts say: Despite fears of cyber attacks, adequate funding and White House focus to counter any new election interference are lagging” at The Guardian’s U.S. edition. Stone, writing a couple of days before Mueller’s statement, noted that “Election security concerns that critics say require more resources and attention include: a paper ballot system to replace or back up electronic voting machines vulnerable to hacking; more resources and attention for cybersecurity programs at the Department of Homeland Security (DHS); a requirement that campaigns report to the FBI any contacts with foreign nationals; and a strong public commitment from the president to an interference-free election…Russia would be remiss not to try again, given how successful they were in 2016,” said Steven Hall, a retired chief of the CIA’s Russian operations…Russian intelligence operatives, Hall added, are likely to be adept at analysing what worked and what didn’t in 2016, stressing that the Kremlin “will try to be more sophisticated in covering their tracks” in 2020, which could make detecting threats harder and require better security measures.” “We tend to fight the last war,” said John Cipher former CIA Russia expert. “Russia is going to look for new ways and vulnerabilities to damage the US.” Given Russia’s capabilities, Democrats have good reason to worry that election security measures in key states could be equally ineffectual.

At Esquire, Charles Pierce has a few choice words in response to Mueller’s warning about continued Russian attacks on our elections: “More significant, at least from this seat, was Mueller’s discussion of the Russian ratfcking of the 2016 election and the ongoing attempts to ratfck the 2020 election. This section of his report is the basis for the “No collusion” half of the “No collusion. No obstruction” litany that everybody down at Camp Runamuck says with their morning prayers, and that Mueller pretty much left as a pointed open question on Wednesday. There was no hoax. There was no coup. There was an attack, and there soon will be others, so saddle up, you idiots…You may recall some stories at the time that alleged the Russians were engaged in some nihilistic, non-partisan ratfcking in order merely to create chaos in the American political system. No, Mueller said on Wednesday. The Russian ratfcking had one definite purpose: the election of Donald Trump. The Russian ratfckers, and the Volga Bagmen behind them, wanted this incompetent, vulgar talking yam to be president.”

Pierce continues, “To believe still that Mueller’s investigation definitively concluded, “No collusion,” you have to believe that all this effort and expense to influence an election in favor of a guy whose businesses already depended on Russian money, and who at the time was trying to close a major real estate deal in Moscow, was all a happy accident, a blessing from above on the Trump campaign. All of this, of course, was in the report. But watching Mueller say it out loud was a compelling bit of theater…And that brings us to the most disappointing thing about Mueller’s brief appearance on Wednesday: his stated reluctance to appear before Congress. He has no excuse left. He is a private citizen now. And if he only repeats what’s in the report, on television, in front of the country, it will contribute mightily to the political momentum behind the demands that Congress do its damn job or shirk its duty entirely. He still needs to testify. He still needs to take questions. He’s only a citizen like the rest of us now, and he has a duty to do the right thing. We all do.”

Despite evidence of growing support for ‘socialist’ ideas, particularly with young voters, polls indicate that GOP red-baiting could cause problems for progressive Democratic candidates with other constituencies. Peter Dreier’s “How Democrats Should Respond to the GOP’s Red-Baiting: Remind them that many of the most popular US programs were once called ‘socialist’” at The Nation provides an antidote. As Dreier observes, “The phrases “social democracy,” “democratic capitalism,” “shareholder capitalism,” or “progressive capitalism” (economist Joseph Stiglitz’s favorite) more accurately describe the evolving consensus among progressive Democrats…Of course, this won’t stop Trump and other Republicans from pinning the socialist label on every Democratic candidate and every Democratic idea…It makes little sense for Pelosi and other party leaders to get defensive when Trump pins a socialist tail on the Democratic donkeys. It would be better to simply explain their vision and practical solutions for America, point out that popular ideas like land-grant colleges, Social Security, public libraries, child-labor laws, the Voting Rights Act, the minimum wage, the Clean Air Act, and Medicare were once called “socialist,” and remind voters that Trump inherited a real-estate empire built on government-backed middle-class housing, squandered his fortune through bankruptcies and mismanagement, used the White House to advance his family business, and cheated on his taxes and his wives.”

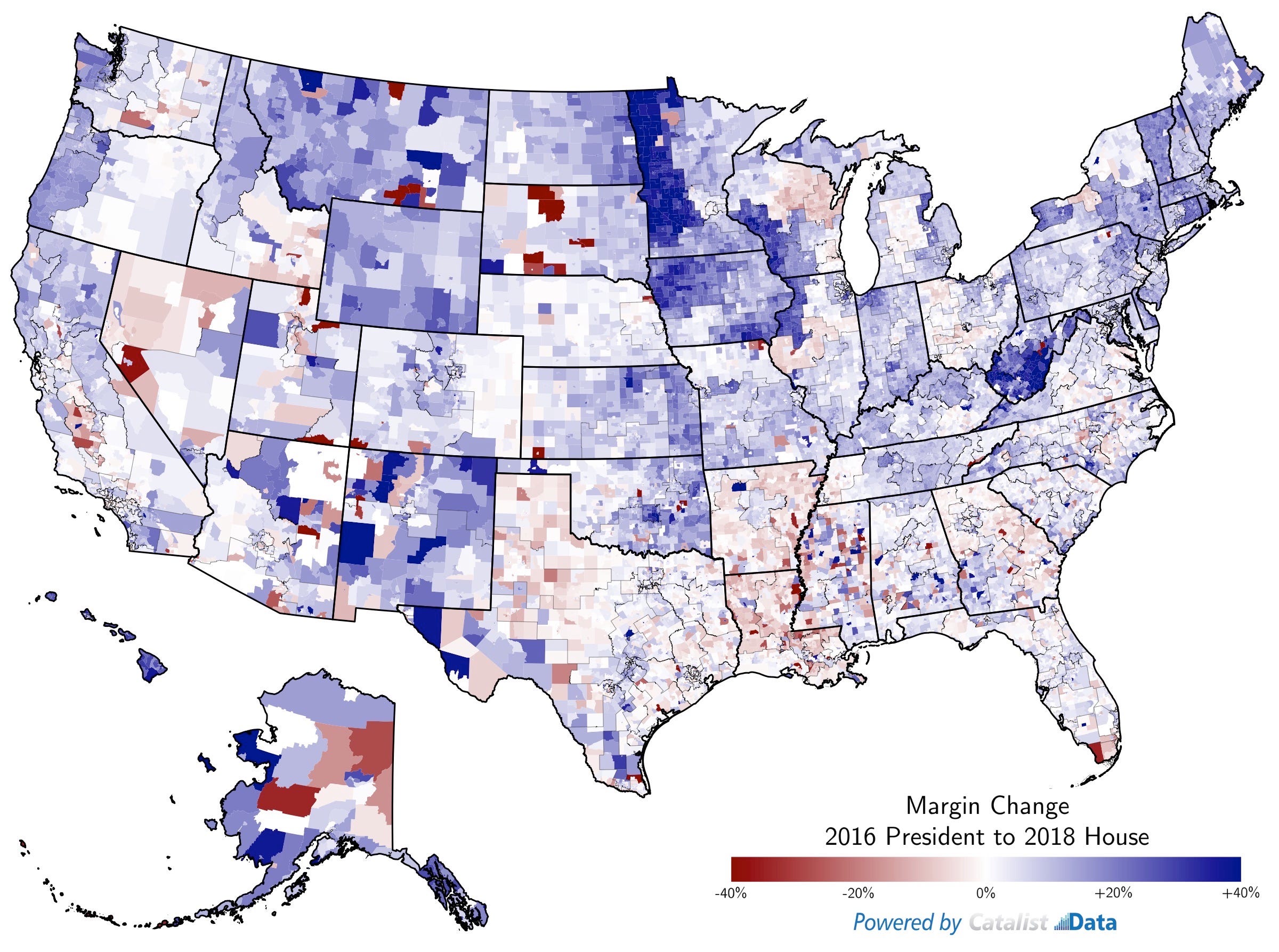

Despite media narratives to the contrary, rural American bounced back towards Democrats in 2018.

Despite media narratives to the contrary, rural American bounced back towards Democrats in 2018.