The following article by Ruy Teixeira, author of The Optimistic Leftist and other works of political analysis, is cross-posted from his blog:

John Cassidy of The New Yorker uses some of my data to make the case that Trump has a great deal to be worried about in Michigan and similar states. I think Cassidy is correct. Remember: almost any erosion in Trump’s margin of support among white noncollege voters in November puts his re-election in extreme danger.

“When Joe Biden entered the Democratic Presidential primary, last spring, he put forward a straightforward case for why he would be the best choice for the Party. In addition to gaining the support of the Democratic Party base, which consists of minority voters and highly educated whites, Biden argued that he could win over some white working-class Americans, particularly in the industrial Midwest, who voted for Donald Trump in 2016. Appearing before a crowd of Teamsters and firefighters in Pittsburgh, Biden said, “If I’m going to be able to beat Donald Trump in 2020, it’s going to happen here.”…

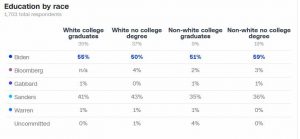

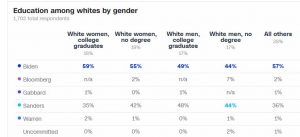

[Y]ou can’t directly translate the results of a Democratic primary to a general election, where the voting pool is much bigger and more conservative. In 2016, about 4.8 million people voted in the general election in Michigan, compared to 1.2 million who voted in the Democratic primary. But you can’t ignore the results of primary elections, either. “You have to be careful about the signal-to-noise ratio, but there is certainly some signal there,” Ruy Teixeira, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and an expert on electoral demographics, told me on Wednesday. “It seems to fit the proposition that Biden is putting forward. If I was part of the Trump campaign, I’d be a little concerned.”That might be an understatement. In a recent analysis of what it will take to win the Presidency in 2020, Teixeira and a colleague, John Halpin, pointed out that in November, 2016, whites without college degrees made up about forty-four per cent of the electorate, making them the largest single group, and Trump carried them by more than twenty points. In 2020, Trump is once more basing his campaign on appealing to these voters and getting more of them to turn out. The good news for the Democrats—and the worrying thing for the President—is that they don’t need to eliminate Trump’s advantage with white working-class voters, which would be a huge task. Given the Democrats’ advantage in other demographics, merely restricting Trump’s advantage with that group to more manageable levels could be sufficient to carry Biden to the White House.

Take Michigan again. In 2016, Trump’s extremely narrow victory there relied on a margin of twenty-one points among whites without college degrees. (He got fifty-seven per cent, and Clinton got thirty-six per cent.) In their analysis, Teixeira and Halpin show that, if Biden can replicate Barack Obama’s performance in 2012, and reduce this margin to ten points, it would help boost his over-all vote in the state by five percentage points. That would virtually guarantee Biden sixteen votes in the electoral college.

“The same analysis applies, with different levels of difficulty, to Pennsylvania and Wisconsin,” Teixeira told me. In Pennsylvania, which Trump won by forty-four thousand votes in 2016, white non-college voters made up fifty-one per cent of the electorate, and Trump carried them by thirty points. According to Teixeira and Halpin’s study, if Biden could reduce this margin by even five points, it “would give the Democrats a several-point cushion in the state.” In Wisconsin, which Trump won by twenty-three thousand votes, whites without college degrees formed an even bigger share of the November, 2016, electorate—fifty-eight per cent—and Trump’s margin was eighteen points.”

Keep your fingers and toes crossed but we are starting to get The Orange One right where we want him.