The following article by Ruy Teixeira, author of The Optimistic Leftist and other works of political analysis, is cross-posted from his blog:

Back during the campaign, I wrote a piece that got around on “Common Sense Democrats“. I argued that “there is a need for political common sense to undergird…debates [within the party]. If polling, trend data, campaign history and/or electoral arithmetic make clear that certain approaches are minimum requirements for success, they should be front-loaded into the discussion. That way discussion can focus on what is truly important instead of endlessly relitigating questions that are essentially settled.

In other words, start with common sense and then build from there. There will still be plenty of room for debates between left and right in the party, but matters of common sense should be neither left nor right. They are simply what is and what anyone’s strategy, whatever their political leanings, must take into account.”

“Democrats should not run against Republicans with positions that are unambiguously unpopular. These include, but are not limited to, defunding the police, abolishing ICE, reparations, abolishing private health insurance and decriminalizing the border. Whatever merits such ideas may have as policy–and these are generally debatable–there is strong evidence that they are quite unpopular with most voters and therefore will operate as a drag on the Democratic electoral and governance success.”

There is another side to this proposition that could be 6a or maybe just a proposition of its own. Just as Democrats should not advocate unpopular policies, they should not advocate popular policies in a way that makes them less popular.

This is brought to mind by the current vogue for attaching the word “equity” to virtually everything the Democrats are advocating and frequently seeming to justify race-neutral and popular polices on the grounds that they would promote racial equity. As politics, this makes no sense. You are taking policies that have great appeal to persuadable voters–otherwise they would not be so popular–and framing them as equity policies, which will reduce their appeal to persuadable voters who have non-liberal views on racial issues.

This is a very bad idea, as this piece from Matt Yglesias’ substack (written not by Matt but by Marc The Intern–nice job Marc!) establishes. The analysis in the piece shows that there are far more persuadables who support progressive economic positions but are non-woke on racial issues than there are those that are woke on racial issues but don’t support progressive economic positions. So framing race-neutral, popular Democratic economic programs as equity programs is a very poor tradeoff in support and electoral terms.

“There’s a growing trend both in media and among elected politicians of deliberately highlighting racial equity as a key argument in favor of left-of-center economic policies.

Two UC Berkeley economists writing in the NYT: “To Reduce Racial Inequality, Raise the Minimum Wage”

Two more academics writing in the NYT: “What Canceling Student Debt Would Do for the Racial Wealth Gap”

And it’s not just in the newspaper. In January, Cory Booker and Ayanna Pressley rolled out a proposal for “baby bonds,” emphasizing the idea that this program would help close the racial wealth gap.

President Joe Biden, 10 days before he took office, described his completely race-neutral small business proposals as prioritizing “Black, Latino, Asian, and Native American owned small businesses.”

None of the actual ideas are bad ideas. We should raise the minimum wage. We should cancel some student debt. We should give more money to poor people (baby bonds are just one way of doing this). We should help small businesses during a pandemic.

It’s also true that these ideas would disproportionately benefit people of color. After all, poor people in America are more likely to be non-white. Literally any policy that helps the poor regardless of race advances racial equity. This is not just true in theory — anti-poverty programs in this country have already reduced racial inequities.

But the premise of this style of argument seems to be that there are lots of people who are skeptical of race-neutral social welfare programs who will become more enthusiastic about them when the policies are framed as winners for racial equity.

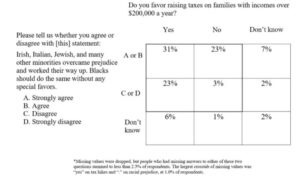

With some help from the Voter Study Group, we can see that data clearly supports that this framing is counterproductive — almost everyone who cares a lot about racial justice also supports an expanded welfare state, whereas lots of people who support progressive economic policies have conservative views on racial justice questions.”

The piece proceed to demonstrate this by marching through a series of crosstabs of views on progressive economic positions with views on racial issues. They are well worth your attention (I reproduce one below, but there are quite a few of them.) The piece concludes:

“[I]t’s completely true that left-of-center economic programs advance racial equity.

But nearly all Democrats would continue to advocate for anti-poverty programs even if the poor were a perfectly racially representative group.

Racial issues are fashionable in progressive circles, so it’s useful in intra-progressive status competitions to say that your pet issue has a racial equity angle. But this approach risks losing many more cross-pressured voters than it has any chance of winning.

Whether you think people are skeptical of things that seem to help some races at the expense of others (this is my take), or if you think Americans are simply really racist (probably someone’s take), the conclusion is actually the same: if you want to advance racial justice, you have to win first. And you can’t win by alienating all the populists.

This was conventional wisdom until very recently. Obama knew focusing on race would hurt him, allowing him to be popular enough to win states like Indiana once and Florida, Ohio, and Iowa twice…..

So I don’t think this should be taboo to say: Americans, on average, are in line with (or even to the left of) Democrats on economics, but they are not in line with the Democrats’ new focus on making everything about race, including the very economic ideas that give them a fighting chance to win elections.”

Please read the entire article; it’s an important piece.