The following article by Ruy Teixeira, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, politics editor of The Liberal Patriot newsletter and co-author with John B. Judis of the new Book “Where Have All the Democrats Gone?,” is cross-posted from The Liberal Patriot:

The Democrats seem to have a “What, me worry?” take on their ongoing loss of working-class (noncollege) voters. That take has several components: white working-class voters who support Trump/Republicans are racist reactionaries who Democrats can’t reach; nonwhite working-class voters who vote Republican are just voting their ideology and so too are beyond persuasion by Democrats; working-class voters are declining as a share of voters over time (and the college-educated are increasing) so the Democrats’ problems will solve themselves; and trying to reach persuadable working-class voters by moving to the center would alienate left progressives and be a net vote-loser.

None of these views are correct.

1. Claim: white working-class voters who support Trump/Republicans are racist reactionaries who Democrats can’t reach. This assumes white working-class voters who vote Republican or would consider doing are all cut from the same reactionary, super-conservative cloth. Not so; many can reasonably be characterized as persuadable. Consider the 2016 Trump vote.

When analysts sifted through the wreckage of Democratic performance in 2016 trying to understand where all the Trump voting had come from, some key themes emerged. One was geographical. Across county-level studies, it was clear that low educational levels among whites was a very robust predictor of shifts toward Trump. These studies also indicated that counties that swung toward Trump tended to be dependent on low-skill jobs, relatively poor performers on a range of economic measures and had local economies particularly vulnerable to automation and offshoring. Finally, there was strong evidence that Trump-swinging counties tended to be literally “sick” in the sense that their inhabitants had relatively poor physical health and high mortality due to alcoholism, drug abuse, and suicide.

The picture was more complicated when it came to individual level characteristics related to Trump voting, especially Obama-Trump voting. There were a number of correlates with Trump voting. They included some aspects of economic populism—opposition to cutting Social Security and Medicare, suspicion of free trade and trade agreements, taxing the rich—as well as traditional populist attitudes like anti-elitism and mistrust of experts. But the star of the show, so to speak, was a variable labelled “racial resentment” by political scientists, which many studies showed bore a strengthened relationship to Republican presidential voting in 2016.

This variable is a scale created from questions like: “Irish, Italian, Jewish, and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors.” The variable is widely and uncritically employed by political scientists to indicate racial animus despite the obvious problem that statements such as these correspond closely to a generic conservative view of avenues to social mobility. And indeed political scientists Riley Carney and Ryan Enos have shown that responses to questions like these change very little if you substitute “Nepalese” or “Lithuanians” for blacks. That implies the questions that make up the scale tap views that are not at all specific to blacks. Carney and Enos term these views “just world belief” which sounds quite a bit different from racial resentment.

But in the aftermath of the Trump election, researchers continued to use the same scale with the same name and the same interpretation with no caveats. The strong relationship of the scale to Trump voting was proof, they argued, that Trump support, including vote-switching from Obama to Trump, was simply a matter of activating underlying racism and xenophobia. Imagine though how these studies might have landed if they had tied Trump support to activating just world belief, which is an eminently reasonable interpretation of their star variable, instead of racial resentment. The lack of even a hint of interest in exploring this alternative interpretation strongly suggests that the researchers’ own political beliefs were playing a strong role in how they chose to pursue and present their studies.

In short, they went looking for racism—and they found it.

Other studies played variations on this theme, adding variables around immigration and even trade to the mix, where negative views were presumed to show “status threat” or some other euphemism for racism and xenophobia. As sociologist Stephen Morgan has noted in a series of papers, this amounts to a labeling exercise where issues that have a clear economic component are stripped of that component and reduced to simple indicators of unenlightened social attitudes. Again, it seems clear that researchers’ priors and political beliefs were heavily influencing both their analytical approach and their interpretation of results.

And there is an even deeper problem with the conventional view. Start with a fact that was glossed over or ignored by most studies: trends in so-called racial resentment went in the “wrong” direction between the 2012 and 2016 election. That is, fewer whites had high levels of racial resentment in 2016 than 2012. This make racial resentment an odd candidate to explain the shift of white voters toward Donald Trump in the 2016 election.

Political scientists Justin Grimmer and William Marble investigated this conundrum intensively by looking directly at whether an indicator like racial resentment really could explain, or account for, the shift of millions of white votes toward Trump. The studies that gave pride of place to racial resentment as an explanation for Trump’s victory did no such accounting; they simply showed a stronger relationship between this variable and Republican voting in 2016 and thought they’d provided a complete explanation.

They had not. When you look at the actual population of voters and how racial resentment was distributed in 2016, as Grimmer and Marble did, it turns out that the racial resentment explanation simply does not fit what really happened in terms of voter shifts. A rigorous accounting of vote shifts toward Trump shows instead that they were primarily among whites, especially low education whites, with moderate views on race and immigration, not whites with high levels of racial resentment. In fact, Trump actually netted fewer votes among whites with high levels of racial resentment than Mitt Romney did in 2012.

So much for the racial resentment explanation of Trump’s victory. Not only is racial resentment a misnamed variable that does not mean what people think it means, it literally cannot account for the actual shifts that occurred in the 2016 election. Clearly a much more complex explanation for Trump’s victory was—or should have been—in order, integrating negative views on immigration, trade and liberal elites with a sense of unfairness rooted in just world belief. That would have helped Democrats understand why voters in Trump-shifting counties, whose ways of life were being torn asunder by economic and social change, were so attracted to Trump’s appeals.

Grimmer and Marble, with Cole Tanigawa-Lau, followed up that initial study with one that included data from the 2020 election. Grimmer summed up their findings this way:

Our findings provide an important correction to a popular narrative about how Trump won office. Hillary Clinton argued that Trump supporters could be placed in a “basket of deplorables.” And election-night pundits and even some academics have claimed that Trump’s victory was the result of appealing to white Americans’ racist and xenophobic attitudes. We show this conventional wisdom is (at best) incomplete. Trump’s supporters were less xenophobic than prior Republican candidates’ [supporters], less sexist, had lower animus to minority groups, and lower levels of racial resentment. Far from deplorables, Trump voters were, on average, more tolerant and understanding than voters for prior Republican candidates…

[The data] point to two important and undeniable facts. First, analyses focused on vote choice alone cannot tell us where candidates receive support. We must know the size of groups and who turns out to vote. And we cannot confuse candidates’ rhetoric with the voters who support them, because voters might support the candidate despite the rhetoric, not because of it.

This sounds more like voters who aren’t being reached by Democrats than voters who can’t be reached by Democrats.

2. Claim: nonwhite working-class voters who vote Republican are just voting their ideology and so are beyond persuasion by Democrats. But it is white college graduates not white working-class or nonwhite voters who are most constrained in their ideology. As Echelon Insights’ Patrick Ruffini has noted, white college graduates exhibit the most ideological consistency in the electorate—just 38 percent are in the middle on an ideological consistency scale, not consistently conservative or liberal. In contrast, 83 percent of black voters, 77 percent of Hispanic voters, 69 percent of Asian voters, and 58 percent of white working-class voters are in the middle group. Notably only 31 percent of white working-class voters are consistently conservative, contrary to the lazy presumptions of most Democrats.

And white college graduates, while more ideologically consistent, are not an adequate fix for Democrats’ working-class problems. It is important not to confuse white college graduates overall with white college Democrats. Most white college graduates are not liberal; this is true only of white college Democrats, who have indeed become much more liberal (and ideologically consistent) over time. But white college graduates as a whole are not particularly liberal. In a survey of more than 6,000 adults that I helped conduct between late March and May of last year with the American Enterprise Institute’s Survey Center on American Life (SCAL) and the nonpartisan research institute NORC at the University of Chicago, 28 percent of these voters identified as liberal. The overwhelming majority said they were moderate (45 percent) or conservative (26 percent).

As for nonwhite working-class voters, it is true that more are voting their ideology. But this is no reason for Democrats to throw up their hands and say, in effect, there’s nothing that we can do. They simply can’t afford to sustain significantly larger losses among these voters without fatally undercutting their coalition. Recent polling data make this brutally obvious.

In the latest New York Times/Siena poll, Biden leads Trump by a mere 17 points among this demographic. This compares to his lead over Trump of 48 points in 2020. And even that lead was a big drop-off from Obama’s 67-point advantage in 2012. The trend line is not good.

Why is this happening? The beginning of wisdom is understanding that the nonwhite working class is not particularly progressive while the Democratic Party has become more so. In the Times poll, these voters overwhelmingly say they are moderate-to-conservative, with less than a quarter identifying as liberal. This has created increased contradictions between the Democratic Party and the nonwhite working-class voters they have relied upon for huge margins to make up for shortfalls elsewhere.

Data from the SCAL/NORC survey exposes these contradictions by allowing the views of moderate-to-conservative nonwhite working-class voters to be examined in detail. My analysis shows many large differences between standard Democratic Party positions and the views of these nonwhite working-class voters. As just one example, consider the issue of “structural racism.”

Is racism “built into our society, including into its policies and institutions,” as held by current Democratic Party orthodoxy, or does racism “come from individuals who hold racist views, not from our society and institutions?” In the SCAL/NORC survey, by 61 to 39 percent, moderate-to-conservative nonwhite working-class voters (70 percent of whom are moderate, not conservative) chose the latter view, that racism comes from individuals, not society. In stark contrast, the comparatively tiny group of nonwhite college graduate liberals favored the structural racism position by 78 to 20 percent. White college graduate liberals were even more lop-sided at 82 to 18 percent. That tells you a lot about who influences the Democratic Party today and who does not.

Thus, the nonwhite working class is not super-liberal. But neither are they super-conservative. As the numbers cited here indicate, they are more mixed in their views and thus subject to persuasion. Thinking nonwhite working-class defections are simply a matter of conservative ideology coming to the fore would be a big mistake, even if many Democrats find it comforting.

3. Claim: since working-class voters are declining as a share of voters over time (and the college-educated are increasing), Democrats’ problems will solve themselves. The trend is correct but the interpretation is not. It is the case today and will be the case going forward that working-class voters will still dominate the electorate. They will be the overwhelming majority of eligible voters (around two-thirds) in 2024 and, even allowing for turnout patterns, only slightly less dominant among actual voters (around three-fifths). Moreover, in all six key swing states—Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin—the working-class share of the electorate, both as eligible voters and as projected 2024 voters, will be higher than the national average.

As I have noted, because we now live in the Upside Down, Democrats reliably win the college-educated but lose the working class. That means that, given the disproportion between the two groups, Democrats need to win the college-educated by way more than they lose the working class to win elections. That is mathematically possible but very challenging—and the worse the working-class deficit gets the more challenging it becomes.

To get a sense of this challenge, consider that in the Times poll previously mentioned, Biden’s deficit among working-class voters was 17 points, 13 points worse than his 4-point deficit in 2020. This is consistent with other polls which generally have Biden’s working-class deficit in the mid-teens. Benchmarking off a 15-point working-class deficit, Biden would have to carry college-educated voters by 33 points in this scenario to replicate his 2020 national showing. That would be quite a jump from his 18-point advantage in that election. Not impossible of course but very, very difficult and shows how much this disproportion could matter in 2024.

Nor will this disproportion go away tomorrow. Estimates from the States of Change project have the working class proportion of eligible voters dropping only slowly from 67 percent today to 62 percent in 2036.

4. Claim: trying to reach persuadable working-class voters by moving to the center would alienate left progressives and be a net vote-loser. The concept that Democrats should shy away from moving to the center because the progressive left will take their toys and go home is ludicrous. This view is backed up what is essentially a threat: if Democrats don’t move in the direction recommended by the progressive left, “their” voters, especially young voters, will fail to be “energized” in 2024, endangering Biden’s re-election and Democratic electoral prospects generally.

But is that really true? Leaving aside the question of whether that would be a responsible use of their power (I don’t think so), do they even have that kind of power? I doubt it. In fact, I think the progressive left is more of a paper tiger, claiming power and influence way above what they actually have.

Start with the fundamental fact that the progressive or intersectional left, for whom issues from ending fossil fuels to open borders to decriminalizing and decolonizing everything (free Palestine!) are inseparably linked moral commitments, is actually a pretty small slice of voters—six percent in the Pew typology (“progressive left”), eight percent in the More in Common typology(“progressive activists”). So we should ask whether and to what extent their commitments are reflected in the views of the voter groups in whose name they claim to speak.

Probably the most important of these is young voters, lately lionized as Democrats’ best hope—but also perhaps their downfall, if not appropriately catered to. And it is true that young voters generally lean more left than older voters. But that does not mean that young voters as a group are flaming left-wingers. Far from it. Indeed, in the Pew typology, the “progressive left” group among those under 30 is only 5 points more (11 percent) than among the population as a whole.

This can be seen on many issues. One such is how to tackle the problem of climate change. The progressive left is in a state of perpetual outrage that the country is not moving faster to get rid of fossil fuels and transition to renewable (e.g., wind and solar) energy, the alleged solution to the problem. This too is supposed to be an issue where the Biden administration is out of sync with younger voters, who therefore will fail to be energized by his re-election bid. Fear of this possibility was presumably why the Biden administration caved to pressure from climate activists and halted permitting on liquified natural gas (LNG) exports, a decision that makes no policy sense and seems likely to alienate working-class voters.

But is it really true that young voters in their tens of millions are demanding moves like this? In the SCAL/NORC survey cited earlier, respondents were asked about their preferences for the country’s energy supply. By 64 percent to 36 percent, Millennial/Gen Z (18-44 year old) voters favored “Use a mix of energy sources including oil, coal and natural gas along with renewable energy sources” over “Phase out the use of oil, coal and natural gas completely, relying instead on renewable energy sources such as wind and solar power only.” This does not seem consistent with the mantra of progressive left activists.

Similarly, in a 3,000 voter survey conducted by YouGov for The Liberal Patriot last June, the following choices were offered to voters about energy strategy:

We need a rapid green transition to end the use of fossil fuels and replace them with fully renewable energy sources;

We need an “all-of-the above” strategy that provides abundant and cheap energy from multiple sources including oil and gas to renewables to advanced nuclear power; or

We need to stop the push to replace domestic oil and gas production with unproven green energy projects that raise costs and undercut jobs.

Among the same Millennial/Gen Z (18-44 year old) voters, the progressive left-preferred first position, emphasizing ending the use of fossil fuels and rapidly adopting renewables, is a distinctly minoritarian one, embraced by just 36 percent of these voters. The most popular position is the second, all-of-the above approach that emphasizes energy abundance and the use of fossil fuels and renewables and nuclear, favored by 48 percent of Millennial/Gen Z voters. Another 16 percent flat-out support production of fossil fuels and oppose green energy projects. Together that’s 64 percent of these voters who are not singing from the progressive left hymnbook.

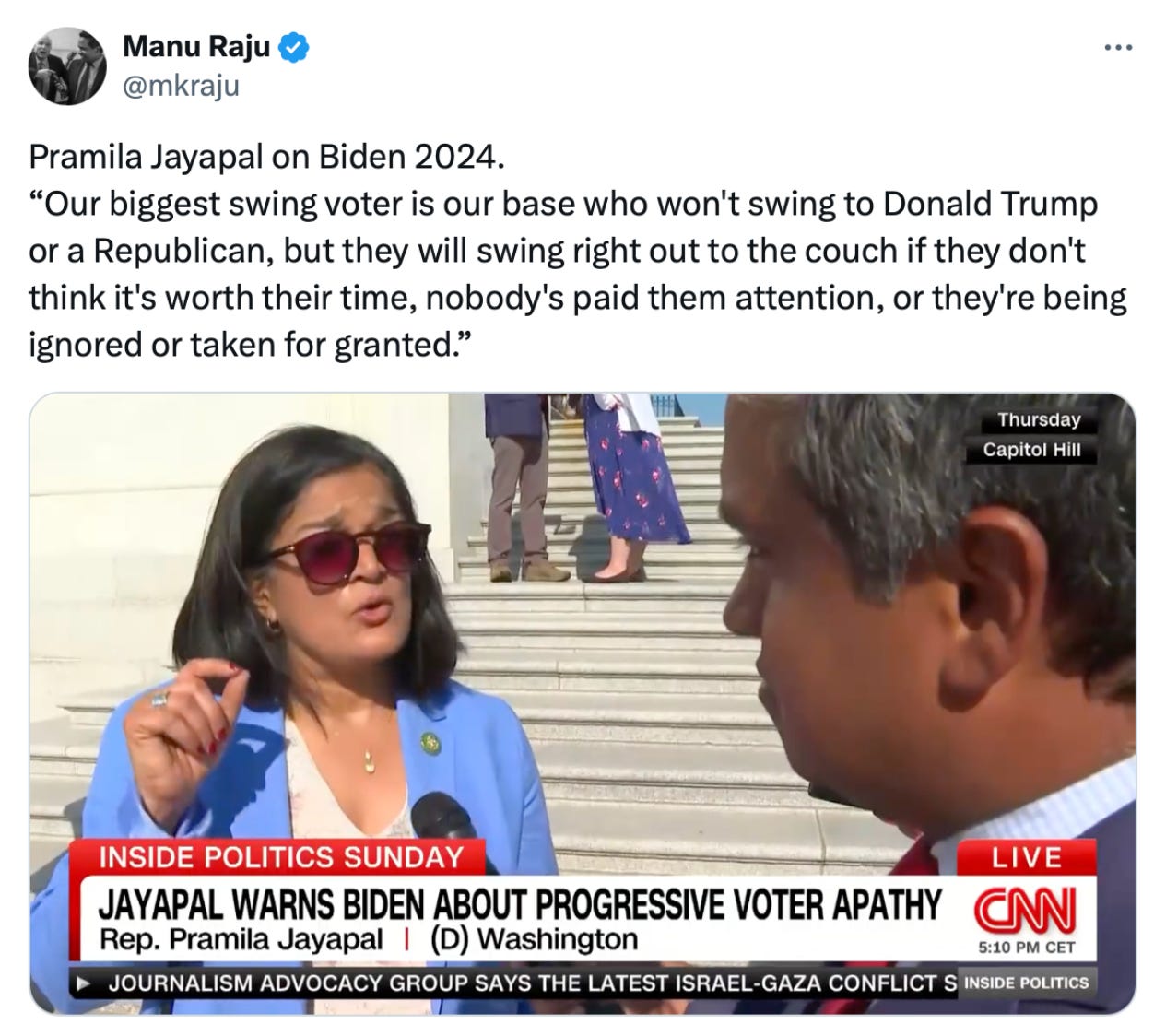

So the progressive left’s claim that failing to embrace their positions is the death-knell for Democrats among younger generation voters is highly suspect. Indeed when progressive left politicians like the ever-reliable and ever-wrong Seattle congresswoman Pramila Jayapal, chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, say things like this…

In reality, tacking to the center may lose a few voters in the progressive hard core—which is small—who choose not to vote or vote for a minor party (they’re unlikely to vote for Trump), but the tradeoff in ability to reach more moderate, especially working class, voters would be well worth it. And potentially crucial in a tight race. That’s why a “What, me worry?” attitude toward the working class and bending over backwards to please the progressive left is a luxury Democrats cannot afford.