The following article by Ruy Teixeira, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, politics editor of The Liberal Patriot newsletter and co-author with John B. Judis of the new Book “Where Have All the Democrats Gone?,” is cross-posted from The Liberal Patriot:

What’s wrong with this picture? The Republican Party seems a shambles, with the unpopular, erratic Trump, with all his massive baggage, as their standard-bearer. Yet the Democrats’ standard-bearer, Biden, is equally if not more unpopular.

For the last six months, Biden’s approval rating has been in the 39-41 percent approval range with 54-56 percent disapproval. As Harry Enten points out “Biden is the least popular elected incumbent at this point in his reelection bid since World War II.”

And critically, trial heats pitting Biden against Trump have consistently shown Biden running behind. Indeed, Biden hasn’t had a lead of any kind in the RCP running average since September of last year (though the race has tightened a bit in recent weeks). That compares to a Biden lead of over six points at this point in the cycle four years ago. As Enten also notes:

[A] lead of any margin for Trump was unheard of during the 2020 campaign—not a single poll that met CNN’s standards for publication showed Trump leading Biden nationally.

Biden is also running behind Trump in six of seven key swing states, consistent with his failure to establish a solid lead in the national popular vote.

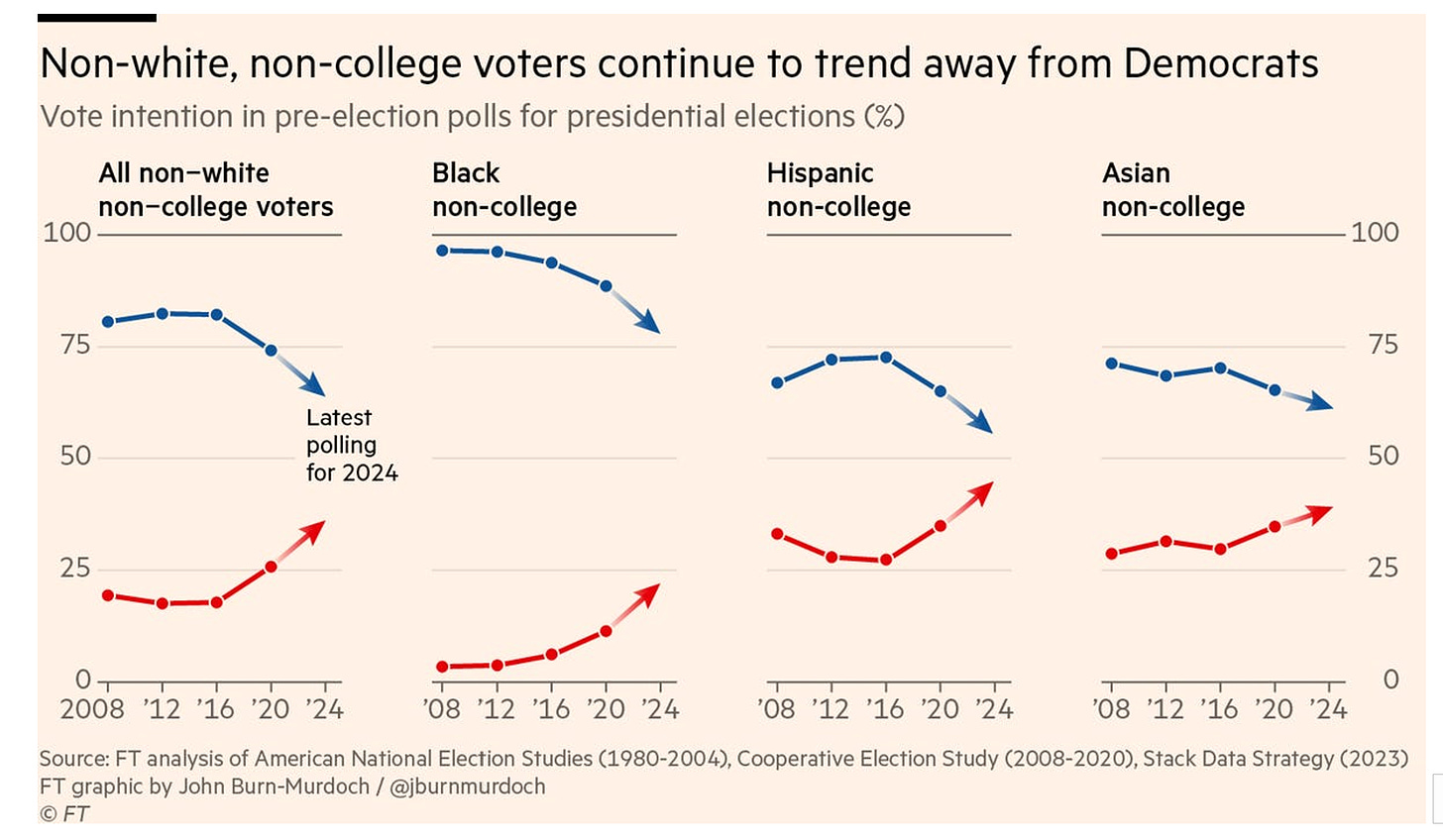

In addition, Democratic Party identification has been declining throughout Biden’s presidency and is now at its lowest level since 1988. Looming over this trend and all the other rough results for the Democrats cited here is the indisputable fact that Democratic poor performance is being driven by defections among working-class (noncollege) voters of all races. Polling consistently shows Biden running deficits among working class voters in the mid-teens, a dramatic fall-off from the 4-point deficit he experienced in the 2020 election.

It’s time to admit that the Democratic party brand is in deep, deep trouble, especially with working-class voters. That is why the Democrats cannot decisively beat Trump and the Republicans, despite the latter’s many liabilities, and find themselves fighting desperately at the 50 yard line of American politics. So it is and so it will continue to be until Democrats figure out how to stop the bleeding with working-class voters.

That means the Democratic approach needs to change. Here’s my three point plan for doing so, originally put forward in October of 2022 and more relevant than ever.

1. Democrats Must Move to the Center on Cultural Issues

2. Democrats Must Promote an Abundance Agenda

3. Democrats Must Embrace Patriotism and Liberal Nationalism

I expand on each of these points below.

The Culture Problem

Here’s the deal (as Biden might put it): the cultural left in and around the Democratic Party has managed to associate the party with a series of views on crime, immigration, policing, free speech and of course race and gender that are quite far from those of the median voter. These unpopular views are further amplified by Democratic-leaning media and nonprofits, as well as within the Democratic Party infrastructure itself, all of which are thoroughly dominated by the cultural left. In an era when a party’s national brand increasingly defines state and even local electoral contests, Democratic candidates have a very hard time shaking these cultural left associations.

As a direct result of these associations, the party’s—or, at least, Biden’s—attempt to rebrand Democrats as a unifying party speaking for Americans across divisions of race and class appears to have failed. Voters are not sure Democrats can look beyond identity politics to ensure public safety, secure borders, high quality, non-ideological education, and economic progress for all Americans.

Instead, Democrats continue to be weighed down by those whose tendency is to oppose firm action to control crime or the southern border as concessions to racism, interpret concerns about ideological school curricula and lowering educational standards as manifestations of white supremacy, and generally emphasize the identity politics angle of virtually every issue. With this baggage, rebranding the party as a whole is very difficult, since decisive action that might lead to such a rebranding is immediately undercut by a torrent of criticism. Democratic candidates in competitive races certainly try to rebrand on an individual level but their ability to escape the gravitational pull of the national party is limited.

Have things improved on this front in the course of the Biden administration? I don’t think so. A Liberal Patriot/YouGov poll found that more voters thought the Democrats had moved too far left on cultural and social issues (61 percent) than thought the Republicans had moved too far right on these issues (58 percent). In the latest Wall Street Journal poll, Trump is preferred over Biden by 17 points on reducing crime and 30 points on securing the border, now the second most important voting issue after the economy.

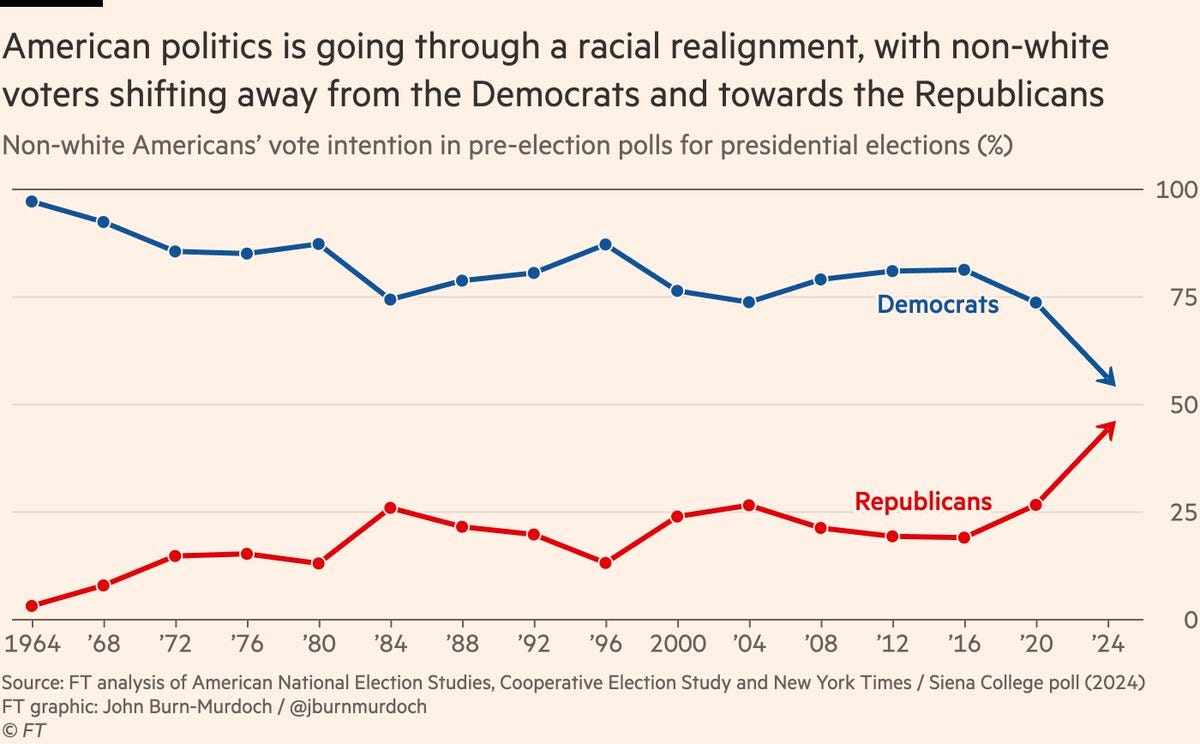

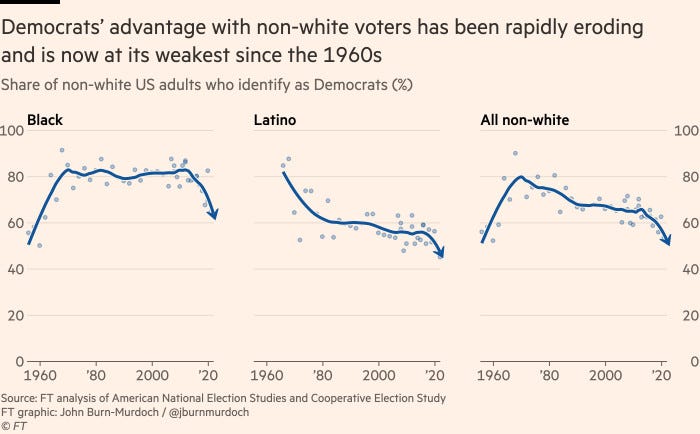

One of the most fascinating aspects of Democrats’ steady movement to the cultural left and ever “woker” stances on these issues is the steady movement of the intended audience for these stances away from the Democrats. These charts by John Burn-Murdoch of the Financial Times illustrate this trend. Whatever else the Democrats’ left turn on cultural issues is accomplishing, it’s not doing them much good among the nonwhite voters—especially nonwhite working-class voters—who, activists assured them, were thirsting for the maximally “progressive” position on these issues.

This wasn’t supposed to happen! But it is. As Burn-Murdoch notes:

The image of the GOP as the party of wealthy country club elites is dimming, opening the door to working- and middle-class voters of all ethnicities…More ominous for the Democrats is a less widely understood dynamic: many of America’s non-white voters have long held much more conservative views than their voting patterns would suggest.

This is staring to bite as Democrats’ cultural evolution takes them farther and farther away from the comfort zone of these voters. Damon Linker describes the process well in a recent post on his Substack:

Our polity is deeply divided over politics, with Democrats and Republicans often residing in morally and epistemologically distinct worlds, and each side viewing the country’s history, current condition, and possible futures very differently. But there’s also a common public culture all Americans share and take part in. It is governed by certain implicit norms and expectations that apply to everyone.

But who determines those norms and expectations? The answer is that these days it is often progressive activists. How do they accomplish this exercise of political-cultural power? I will admit that I’m not entirely sure. Something like the following process appears to happen: A group of left-leaning activists declares that certain words, claims, or arguments should be considered anathema, tainted as they supposedly are with prejudice, bigotry, racism, sexism, xenophobia, homophobia, or transphobia; then people in authoritative positions within public and private institutions (government, administrative and regulatory agencies, universities, corporations, media platforms, etc.) defer to the activists, adjusting the language they use to conform to new norms; and then, once the norms and expectations have been adjusted, a new round of changes gets mandated by the activists and the whole process repeats again, and again, and again.

I suspect that to many millions of Americans (and to lots of people living in democracies across the world where something similar is going on) the process feels a bit like a rolling moral revolution without end that makes them deeply uncomfortable. That response is no doubt a function of right-leaning views among some voters. But I’d be willing to bet that for many others, the negative reaction follows from the sheer bossiness of it, with schools, government bureaucrats, HR departments at work, movie stars, and others constantly declaring: You can’t talk that way anymore; you must speak this other way now; those words are bad; these words are the correct ones. A lot of people are ok with this. But many others respond with: Who the f-ck are you to tell me how I’m allowed to talk? Who elected or appointed you as my moral overseer and judge?

To many voters, especially working-class voters, this is the world Democrats are bequeathing to them and they flat-out don’t like it. And that’s important! I never cease to be amazed by Democrats’ touching, if delusional, faith that they can simply turn up the volume on economic issues and ignore these sentiments. Culture matters and the issues to which they are connected matter. They are a hugely important part of how voters assess who is on their side and who is not; whose philosophy they can identify with and whose they can’t.

Instead, for many working-class voters to seriously consider their economic pitch, Democrats need to convince them that they are not looked down on, that their concerns are taken seriously and that their views on culturally freighted issues will not be summarily dismissed as unenlightened.

Democrats would do well to remember the following as they contemplate the challenge of reaching more working class voters:

- It is not the working class that sees the police as an unnecessary evil and opposes rigorous enforcement of the law for public safety and public order.

- It is not the working class that believes public consumption of hard drugs should be tolerated, with intervention limited to reviving addicts when they overdose.

- It is not the working class that believes many crimes like shoplifting should be decriminalized because punishing the perpetrators would have “disparate impact”.

- It is not the working class that believes you should never refer to illegal immigrants as “illegal” and that border security is somehow a racist idea.

- It is not the working class that believes an overwhelming surge of migrants at the southern border should be accommodated with asylum claims, parole arrangements, and release into urban areas around the country.

- It is not the working class that believes competitive admissions and job placements should be allocated on the basis of race (“equity”) not merit.

- It is not the working class that views objective tests as fundamentally flawed if they show racial disparities in achievement.

- It is not the working class that believes America is a structurally racist, white supremacist society.

- It is not the working class that sees patriotism as a dirty word and the history of the United States as a bleak landscape of racism and oppression.

- It is not the working class that thinks sex is “assigned at birth” and can be changed by self-conception, rather than being an objective, biological reality.

- It is not the working class that thinks it’s a great idea to police the language people use for hidden “microaggressions” and bias against the “marginalized”.

- And it is definitely not the working class that believes in “decolonize everything” and manages to see murderous thugs like Hamas as righteous liberators of a subaltern people.

To reach the working class, Democrats will have to move to the center on all these issues. There really is no alternative.

The Abundance Problem

Abundance means just what you think it means: more stuff, more growth, more opportunity, being able to easily afford life’s necessities with a lot left over. In short, nicer, genuinely comfortable lives for all.

That’s what voters, especially working-class voters, want. But that’s not what they feel they’re getting. Consider these poll results, all from the last month.

1. In the latest New York Times/Siena poll, only about a quarter (26 percent) describe economic conditions today as excellent or good, compared to 74 percent who say they are only fair or poor. This represents some modest improvement from the middle of last year, but it is obviously still quite low. Among working-class (noncollege) voters, sentiments are particularly negative: just 20 percent have a positive view of economic conditions, while 80 percent are negative. These views are actually slightly more negative among nonwhite working-class voters: 19 percent positive vs. 81 percent negative.

Voters are more positive about their personal financial situation, about split down the middle between excellent/good and only fair/poor. But they are far more likely to say that Biden’s policies have hurt them personally (43 percent) than helped them (18 percent) and that Trump’s policies helped them personally (40 percent) rather than hurt them (25 percent). Less than a quarter (23 percent) believe the economy is better than it was a year and less than a fifth (19 percent) believe it is better than four years ago. And voters’ attitudes are very negative in a wide range of economic areas: prices for food and consumer goods (88 percent only fair or poor); the housing market (79 percent); gas prices (83 percent); and wages and incomes (70 percent). On all these economic questions the views of working-class voters are distinctly more negative than voters overall.

2. In the latest CBS News poll, just 23 percent say their personal financial situation has gotten better in the last few years compared to 55 percent who say it has worsened (29 percent say no change). Looking back on the economy during the Trump presidency, by 65 to 28 percent respondents characterize it as good rather than bad, while the Biden economy is viewed as bad by 59 to 38 percent. The same pattern is evident on whether prices will go up or down under the policies of a future Biden or Trump presidency: people overwhelmingly feel prices will go up rather than down under Biden (55 to 17 percent) while believing prices will go down rather than up under Trump (44 to 34 percent).

3. In the latest Wall Street Journal poll, by 57 to 31 percent voters believe the economy has gotten worse rather than better over the last two years. They believe by 68 to 28 percent that inflation has gone in the wrong rather than right direction over the past year, by 50 to 43 percent that their personal financial situation has gone in the wrong direction, and by 65 to 25 percent that the ability of the average person to get ahead has gone in the wrong direction. And in a final finding, which perhaps best captures what all these data are telling us, when voters are given the choice between what has increased more in the last few years, their household income or the costs of everyday goods and services (or both at the same rate), they choose everyday costs over household income by a whopping 74 to 7 percent.

There’s a lot more recent data along these lines but you get the idea. Abundance this ain’t. Now it’s possible that improving conditions may produce a sudden positive spike in voters’ feelings about the economy in general and Biden’s stewardship of it. But so far we just haven’t seen this (though as noted, there has been some modest diminution in the intensity of negative feelings).

There has been some debate about the significance of consumer sentiment and changes thereof during the Biden administration. The two main trackers of consumer sentiment are the University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Sentiment and the Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Survey. Both have been depressed through much of Biden’s term but the Michigan index much more so because it is more closely tied to pocketbook conditions and hence more sensitive to inflation. But both started moving sharply in a positive direction in last December and this January, leading to a spat of optimism that voters’ views of the economy and Biden’s stewardship might improve dramatically. As noted, that hasn’t happened and disappointingly the upward movement in both measures has basically stopped since January.

In Democratic circles, there are two main responses to this (so far) bleak record on the abundance front. The first is what I call the “deluded, ungrateful wretches” theory. The idea here is that the economy’s recent record has been stellar: very low unemployment, strong job creation, smartly rising wages and inflation that has declined sharply from recent highs (though it is still significantly elevated from normal rates and the most recent inflation report came in higher than expected). Given all this, why do voters still believe the economy is so bad? They’re deluded! And why don’t they give the Biden administration the credit it richly deserves for this stellar performance? They’re ungrateful! The shockingly high number of deluded, ungrateful wretches is variously attributed to partisanship, the baleful influence of the media (especially conservative media), and voter distrust of economic experts and official statistics. Pretty much anything other than things aren’t—and haven’t been—all that great.

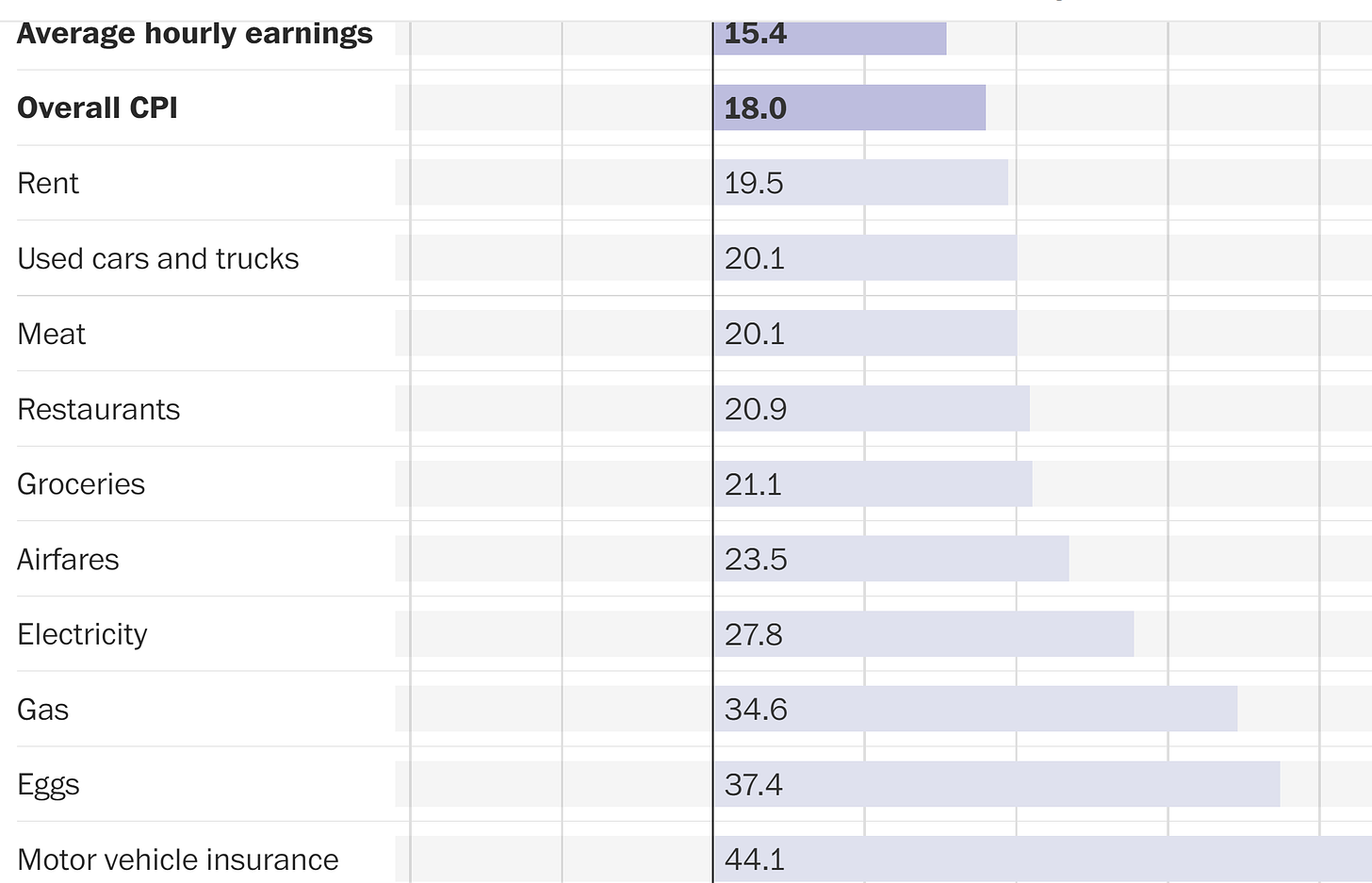

But there’s quite a strong case that, in terms of the “lived experience” of voters, particularly working-class voters, things have not in fact been great. The primary suspect of course is inflation which is still relatively high and in June of 2022 reached 9 percent, the highest inflation rate the country had experienced since 1981. People absolutely hate inflation since it directly undercuts living standards and they are reminded of this fact when they do mundane things like go to the grocery store. Heather Long of the Washington Post recently collected data on changes in inflation, hourly earnings and household purchases since Biden took office, shown below.

As the chart shows, cumulative inflation has outpaced average hourly earning growth and the rise in many consumer prices have been even larger than overall inflation: rent and meat (up 20 percent); restaurants and groceries (21 percent); electricity (28 percent); gas (35 percent); and eggs (37 percent). These are facts of economic life that voters have a hard time forgetting.

More broadly, economics commentator Roger Lowenstein reminds us that real median household income went up 10.5 percent under Trump before the pandemic hit. In contrast:

[Under Biden], inflation has snatched away the gains from even a very strong labor market. Over his first two years, as price hikes outran wages, real median household income fell 2.7 percent. The census has yet to report median income for 2023, but given that real wages were up about 1 percent through November, the cumulative change in household median income, adjusted for inflation, over Mr. Biden’s first three years is likely to be in the range of mildly negative to very mildly positive. In other words, in the all-important category of improving living standards, the country did not make progress.

This certainly helps explain why many voters look back fondly on the Trump economy while being quite negative about the Biden economy. It doesn’t matter whether Trump “caused” the strong economic performance on his watch—it’s still what voters experienced.

And there’s an additional factor that helps explain the depressed economic mood, even as some economic indicators have forged ahead. That is not just the cost of consumer goods but the “cost of money.” A new NBER working paper, “The Cost of Money is Part of the Cost of Living: New Evidence on the Consumer Sentiment Anomaly” by economists Marijn A. Bolhuis, Judd N. L. Cramer, Karl Oskar Schulz and Lawrence H. Summers finds that:

Unemployment is low and inflation is falling, but consumer sentiment remains depressed…We propose that borrowing costs, which have grown at rates they had not reached in decades, do much to explain this gap. The cost of money is not currently included in traditional price indexes, indicating a disconnect between the measures favored by economists and the effective costs borne by consumers. We show that the lows in US consumer sentiment that cannot be explained by unemployment and official inflation are strongly correlated with borrowing costs and consumer credit supply. Concerns over borrowing costs, which have historically tracked the cost of money, are at their highest levels since the Volcker-era. We then develop alternative measures of inflation that include borrowing costs and can account for almost three quarters of the gap in US consumer sentiment in 2023.

Put it all together and the deluded, ungrateful wretches theory seems increasingly untenable. However, the Democrats do have another economic argument which merits consideration. That is that they are playing the long game—laying the basis for future abundance.

They base this claim on the adoption of a new “industrial strategy”, as instantiated in the three big bills passed in Biden’s first two years: the Infrastructure and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the so-called Inflation Reduction Act (mostly a climate spending bill). These bills included $1.5 trillion in new spending to jump-start an economic transformation of the country built around the industries of the future, especially those related to clean energy.

That’s the theory and as theories go it’s not a bad one. Historically, America has worked best when public policy and private initiative have collaborated in service of great national goals. That goes all the way back to the early 19th century American System of infrastructure investment and industry promotion initiated by Alexander Hamilton and includes the great surge of innovation, widely-shared prosperity and American global leadership after World War II.

Thus aggressive public policy along these lines has considerable precedent and justification. But it doesn’t follow that Democrats today have the right strategy and are making the right investments. That’s an open question

What an industrial strategy or policy should accomplish is shifting a country’s output toward emerging industries that become competitively successful and spark overall economic growth and prosperity. Is that happening today? Are the Democrats, once again, on the verge of becoming the party of American prosperity?

Democrats say this is already happening and point to $200 billion in commitments by companies to projects in the semiconductor and clean energy areas. Of course, commitments are not the same as projects being completed but it is true that there has been a remarkable spike in manufacturing construction spending, more than doubling since August of 2022 when the IRA and CHIPS and Science bills were passed. Perhaps not surprisingly, there is an appetite for taking advantage of generous subsidies and tax credits.

But it is also true that growth in overall private investment is sluggish. The boom, such as it is, appears to be highly localized and sector-specific. Moreover, even in manufacturing, total employment has been almost flat since August, 2022 when the IRA/CHIPS and Science were passed; the lion’s share of manufacturing employment growth during the Biden administration has simply replaced jobs lost during the COVID crash. And as Noah Smith points out, manufacturing output hasn’t gone anywhere (in fact, it’s recently been going down) and the manufacturing sector may now even be in a slump.

As Smith also notes there are many obstacles in the way of successful industrial policy, which cannot and should not be reduced to spending a lot of money (“checkism”). Democrats will need considerable time to get it right and “bold, persistent experimentation” à la FDR. Not to mention some serious regulatory and permitting reform and the discarding by Democrats of their absurd commitment to “everything bagel liberalism.”

Here’s why: it’s just too damn hard to build stuff in this country. But Democrats seem more interested in spending money than changing this situation—for example, the modest permitting reforms that Joe Manchin was promised (remember that?) as a condition for his support on the IRA died partially because of lack of support from his own party. But without changing that situation, it’s quite unlikely Democrats can deliver the abundance voters, particularly working-class voters, are looking for. Making it a bit easier for consumers to buy an electric car or a heat pump just isn’t going to cut it.

It’s worth dwelling for a moment on the death of Manchin’s permitting reform and its implications. As has been widely noted, if the IRA’s investments are to actually reduce carbon emissions to the extent the administration and advocates claim, it would depend on an absolutely massive build-out of infrastructure, especially interregional high voltage transmission lines, which will be quite difficult. As noted, it’s very hard to build such things fast in the United States, given permitting and regulatory obstacles. Even with the permitting reform bill, the pace at which this infrastructure could plausibly have been built was likely far below what would be needed to hit administration timetables. Without permitting reform, the pace will be truly glacial.

And it’s not just renewable energy infrastructure that will suffer. There is now a renaissance in nuclear energy—theoretically supported by the IRA—throughout the world, as country after country reverses course and embraces the necessity of a nuclear buildout: the Czech Republic, Netherlands, Poland, South Korea, the UK, and even Japan, which had anathematized nuclear after the 2011 Fukushima incident. But the US will be hard-pressed to participate in this renaissance without regulatory changes that would facilitate the building of new reactors. Instead, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission released a draft of new rules in September, 2022 that would make it harder, not easier, to build them.

Yet without adequate infrastructure and firm power supply from nuclear or fossil fuels, the rapid build-out of wind and solar the Biden administration and climate advocates want is highly unlikely to work the way they envision. But it will stress the grid and likely anger consumers and industry through rising prices and declining reliability.

And Democrats should remember this: working-class voters do not share Democratic elites’ zeal for restructuring the economy around “green” industries and a clean energy transition based around wind, solar and electric vehicles which underpins much of the Democrats’ new industrial strategy. Working-class voters are much more pragmatic and will judge this strategy not by its greenness but by its concrete effects on their lives.

That is the way—the only way—Democrats can truly become the party of abundance American voters are looking for. Right now, they surely are not. Consider that for 74 years, Gallup has been asking a question about which party can do a better job “keeping the country prosperous” in the next several years. In the first part of this period, from 1951 to the election of Ronald Reagan, Democrats had a large and robust advantage on this measure, averaging a 17-point lead over the Republicans. But from the Reagan election on, that advantage has vanished. While there have been many ups and downs, Republicans have averaged a slight advantage (two points) on which party can keep the country prosperous. The last two readings, in fall of 2022 and fall of 2023, had Republicans preferred over the Democrats by 10 and 14 points points, respectively. And among working-class voters, the gap was vast in the last reading: 60 percent of these voters preferred the Republicans and just 33 percent the Democrats.

It would appear that Democrats seriously need to rethink their economic approach and not assume that simply spending more money in their favorite areas (like climate change) is going to do the job. It won’t. Voters are a much tougher audience than that.

The Patriotism Problem

Democrats suffer from a patriotism gap. They are viewed as the less patriotic party and Democrats are less likely than Republicans and independents to view themselves as patriotic. Here are some examples.

1. A Third Way/Impact Research poll in late 2022 found 56 percent of voters characterizing the Republican party as “patriotic,” compared to 46 percent who felt the same about the Democrats.

2. A Survey Center on American Life/NORC poll from May of last year tested the same question among 6,000 respondents and found 63 percent viewing the Republicans as patriotic, compared to just 48 percent who thought the Democrats qualified.

3. In two 3,000 voter surveys conducted by The Liberal Patriot/YouGov in June and September of last year, only 29 percent of voters thought the Democrats were closer to their views on patriotism than the Republicans were, while 43 percent chose the GOP over the Democrats. Among working-class (noncollege) voters, exactly twice as many (48 percent) thought the Republicans were closer to their views on patriotism than thought that about the Democrats (24 percent). Interestingly, among college-educated voters, there was very little difference in how close these voters felt to the two parties on patriotism.

4. In a poll of 2,500 battleground state and district voters last November, PSG/Greenberg Research found an 11-point advantage for Trump and the Republicans over Biden and the Democrats on who would do a better job on “being patriotic.”

5. In Gallup’s latest reading on pride in being an American, 55 percent of Democrats said they were extremely or very proud of being American, compared to 64 percent of independents and 85 percent of Republicans who felt that way. Just 29 percent of Democrats would characterize themselves as “extremely proud,” down 25 points since the beginning of this century.

6. Perhaps most alarming, in a 2022 poll Quinnipiac found that a majority of Democrats (52 percent) said they would leave the country, rather than stay and fight (40 percent), should the United States be invaded as Ukraine was by Russia.

So the patriotism gap is alive, well, and persistent. Why is this? One key factor is that, for a good chunk of the Democrats’ progressive base, being patriotic is just uncool and hard to square with much of their current political outlook. As Brink Lindsey put it in an important essay on “The Loss of Faith”:

The most flamboyantly anti-American rhetoric of 60s radicals is now more or less conventional wisdom among many progressives: America, the land of white supremacy and structural racism and patriarchy, the perpetrator of indigenous displacement and genocide, the world’s biggest polluter, and so on. There are patriotic counter-currents on the center-left—think of Obama’s speech at the 2004 Democratic convention, or Hamilton—but these days both feel awfully dated.

Similarly, liberal commentator Noah Smith observed in an essay simply titled “Try Patriotism”:

I’ve seen a remarkable and pervasive vilification of America become not just widespread but de rigueur among progressives since unrest broke out in the mid-2010s….The general conceit among today’s progressives is that America was founded on racism, that it has never faced up to this fact, and that the most important task for combatting American racism is to force the nation to face up to that “history”….Even if it loses them elections, progressives seem prepared to go down fighting for the idea that America needs to educate its young people about its fundamentally White supremacist character…

That conventional wisdom is a problem. It’s why “progressive activists”—eight percent of the population as categorized by the More in Common group, who are “deeply concerned with issues concerning equity, fairness, and America’s direction today”—are so unenthusiastic about their country. Just 34 percent of progressive activists say they are “proud to be American” compared to 62 percent of Asians, 70 percent of blacks, and 76 percent of Hispanics, the very groups whose interests these activists claim to represent. Similarly, in an Echelon Insights survey, 66 percent of “strong progressives” (about 10 percent of voters) said America is not the greatest country in the world, compared to just 28 percent who said it is. But the multiracial working class (noncollege voters, white and nonwhite) had exactly the reverse view: by 69-23, they said America is the greatest country in the world.

The uncomfortable fact is that these sentiments, and the view of America they represent, are now heavily associated with Democrats by dint of the very significant weight progressive activists carry within the party, which far transcends their actual numbers. Their voice is further amplified by their strong and frequently dominant influence in associated institutions that lean toward the Democrats: nonprofits, foundations, advocacy groups, academia, legacy media, the arts—the commanding heights of cultural production, as it were. It’s just not cool in these circles to be patriotic.

Why does this matter? Most obviously, it puts the Democrats on the wrong side of something that’s quite popular: patriotism and love of country. Even after a decade of decline in our contentious times, 67 percent of the public says they are extremely or very proud of being an American. Another 22 percent say they are moderately proud. And, as Smith correctly observes: “People want to like their country. They can be disappointed in it or mad at it or frustrated with it, but ultimately they want to think that they’re part of something good.” Making people feel bad about the country they live in seems like a recipe for failure.

But the problem goes deeper than simple unpopularity, though that is not insignificant. Lack of patriotism undercuts Democrats’ ability to mobilize a coalition behind what they say they want: a robust and far-reaching program of economic renewal. One of the only effective ways—really, the most effective way—to mobilize Americans behind big projects is to appeal to patriotism, to Americans as part of a nation. Indeed much of what America accomplished in the 20th century was under the banner of liberal nationalism. But many in the Democratic Party blanche at any hint of this approach because of its association with darker impulses and political trends. Yet as John Judis has pointed out, nationalism has its positive side as well in that it allows citizens to identify on a collective level and support projects that serve the common good rather than their immediate interests.

Democrats have tried uniting the country around the need to dismantle “systemic racism” and promote “equity”….and failed. Democrats have tried uniting the country around the need to save the planet through a rapid green transition…and failed. It’s time for Democrats to try something that really could unite the country: patriotism and liberal nationalism.

This approach has a rich heritage. As Peter Juul and I noted in our American Affairs article on “The Case for a New Liberal Nationalism”:

When labor and civil rights leaders A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin put forward their ambitious Freedom Budget for All Americans in 1966, they couched their political argument in the powerful idiom of liberal nationalism. “For better or worse,” Randolph avowed in his introduction, “We are one nation and one people.” The Freedom Budget, he went on, constituted “a challenge to the best traditions and possibilities of America” and “a call to all those who have grown weary of slogans and gestures to rededicate themselves to the cause of social reconstruction.” It was also, he added, “a plea to men of good will to give tangible substance to long-proclaimed ideals.

And it wasn’t just Randolph and Rustin, it was John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King and, of course, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal politics he promulgated. In our new book, Where Have All the Democrats Gone?, John Judis and I put it this way:

[T]he New Deal Democrats were moderate and even small-c conservative in their social outlook. They extolled “the American way of life” (a term popularized in the 1930s); they used patriotic symbols like the “Blue Eagle” to promote their programs. In 1940, Roosevelt’s official campaign song was Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America.” Under Roosevelt, Thanksgiving, Veterans’ Day, and Columbus Day were made into federal holidays. Roosevelt turned the annual Christmas Tree lighting into a national event. Roosevelt’s politics were those of “the people” (a term summed up in Carl Sandburg’s 1936 poem, “The People, Yes”) and of the “forgotten American.” There wasn’t a hint of multiculturalism or tribalism. The Democrats need to follow this example.

If liberal nationalism was good enough for A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, for FDR and JFK and MLK, it should be good enough for today’s Democratic Party. Democrats should proudly proclaim that their party is a patriotic party that believes America as a nation has accomplished great things and been a force for good in the world, a record that can be carried forth into the future.

Funny that progressives should lose track of this. As David Leonhardt pointed out in the podcast I recently did with him:

[J]ust look at history—the civil rights movement carried American flags while marching for civil rights…think about what an incredible favor it was to them when their counter protesters held up confederate flags, the flag of of treason…the labor unions of the early 20th century brought enormous American flags to their rallies…More recently, the gay rights movement used the military in the 90s as this thing that they said, let us join the military.That is patriotism….It worked.

That’s right: it worked. And it can work again.

Leonhardt concluded by quoting labor historian Nelson Lichtenstein:

All of America’s great reform movements from the crusade against slavery onward have defined themselves as champions of a moral and patriotic nationalism which they counterpoised to the parochial and selfish elites who stood athwart their vision of a virtuous society. So the connection really between patriotism and progressivism is long and proud and progressivism will be much more successful if it is willing to embrace patriotism.

Words of wisdom.

That brings us to the end of the three point plan.

1. Democrats Must Move to the Center on Cultural Issues

2. Democrats Must Promote an Abundance Agenda

3. Democrats Must Embrace Patriotism and Liberal Nationalism

So crazy it just might work!