The following article by Ruy Teixeira, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, politics editor of The Liberal Patriot newsletter and co-author with John B. Judis of the new Book “Where Have All the Democrats Gone?,” is cross-posted from The Liberal Patriot:

Last week, I started revisiting my “Three Point Plan to Fix the Democrats and Their Coalition” from October of 2022. A brisk tour of the polling and political data suggested the Democrats are still in need of serious reform and that the three point plan is as relevant as ever. Here’s the very short version of the plan:

1. Democrats Must Move to the Center on Cultural Issues

2. Democrats Must Promote an Abundance Agenda

3. Democrats Must Embrace Patriotism and Liberal Nationalism

Last week I discussed cultural issues. This week I’ll discuss abundance and conclude next week with patriotism.

The Abundance Problem

Abundance means just what you think it means: more stuff, more growth, more opportunity, being able to easily afford life’s necessities with a lot left over. In short, nicer, genuinely comfortable lives for all.

That’s what voters, especially working-class voters, want. But that’s not what they feel they’re getting. Consider these poll results, all from the last month.

1. In the latest New York Times/Siena poll, only about a quarter (26 percent) describe economic conditions today as excellent or good, compared to 74 percent who say they are only fair or poor. This represents some modest improvement from the middle of last year, but it is obviously still quite low. Among working-class (noncollege) voters, sentiments are particularly negative: just 20 percent have a positive view of economic conditions, while 80 percent are negative. These views are actually slightly more negative among nonwhite working-class voters: 19 percent positive vs. 81 percent negative.

Voters are more positive about their personal financial situation, about split down the middle between excellent/good and only fair/poor. But they are far more likely to say that Biden’s policies have hurt them personally (43 percent) than helped them (18 percent) and that Trump’s policies helped them personally (40 percent) rather than hurt them (25 percent). Less than a quarter (23 percent) believe the economy is better than it was a year and less than a fifth (19 percent) believe it is better than four years ago. And voters’ attitudes are very negative in a wide range of economic areas: prices for food and consumer goods (88 percent only fair or poor); the housing market (79 percent); gas prices (83 percent); and wages and incomes (70 percent). On all these economic questions the views of working-class voters are distinctly more negative than voters overall.

2. In the latest CBS News poll, just 23 percent say their personal financial situation has gotten better in the last few years compared to 55 percent who say it has worsened (29 percent say no change). Looking back on the economy during the Trump presidency, by 65 to 28 percent respondents characterize it as good rather than bad, while the Biden economy is viewed as bad by 59 to 38 percent. The same pattern is evident on whether prices will go up or down under the policies of a future Biden or Trump presidency: people overwhelmingly feel prices will go up rather than down under Biden (55 to 17 percent) while believing prices will go down rather than up under Trump (44 to 34 percent).

3. In the latest Wall Street Journal poll, by 57 to 31 percent voters believe the economy has gotten worse rather than better over the last two years. They believe by 68 to 28 percent that inflation has gone in the wrong rather than right direction over the past year, by 50 to 43 percent that their personal financial situation has gone in the wrong direction, and by 65 to 25 percent that the ability of the average person to get ahead has gone in the wrong direction. And in a final finding, which perhaps best captures what all these data are telling us, when voters are given the choice between what has increased more in the last few years, their household income or the costs of everyday goods and services (or both at the same rate), they choose everyday costs over household income by a whopping 74 to 7 percent.

There’s a lot more recent data along these lines but you get the idea. Abundance this ain’t. Now it’s possible that improving conditions may produce a sudden positive spike in voters’ feelings about the economy in general and Biden’s stewardship of it. But so far we just haven’t seen this (though as noted, there has been some modest diminution in the intensity of negative feelings).

There has been some debate about the significance of consumer sentiment and changes thereof during the Biden administration. The two main trackers of consumer sentiment are the University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Sentiment and the Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Survey. Both have been depressed through much of Biden’s term but the Michigan index much more so because it is more closely tied to pocketbook conditions and hence more sensitive to inflation. But both started moving sharply in a positive direction in last December and this January, leading to a spat of optimism that voters’ views of the economy and Biden’s stewardship might improve dramatically. As noted, that hasn’t happened and disappointingly the upward movement in both measures stopped in February (actually down slightly) and March (flat).

In Democratic circles, there are two main responses to this (so far) bleak record on the abundance front. The first is what I call the “deluded, ungrateful wretches” theory. The idea here is that the economy’s recent record has been stellar: very low unemployment, strong job creation, smartly rising wages and inflation that has declined sharply from recent highs (though it is still significantly elevated from normal rates). Given all this, why do voters still believe the economy is so bad? They’re deluded! And why don’t they give the Biden administration the credit it richly deserves for this stellar performance? They’re ungrateful! The shockingly high number of deluded, ungrateful wretches is variously attributed to partisanship, the baleful influence of the media (especially conservative media), and voter distrust of economic experts and official statistics. Pretty much anything other than things aren’t—and haven’t been—all that great.

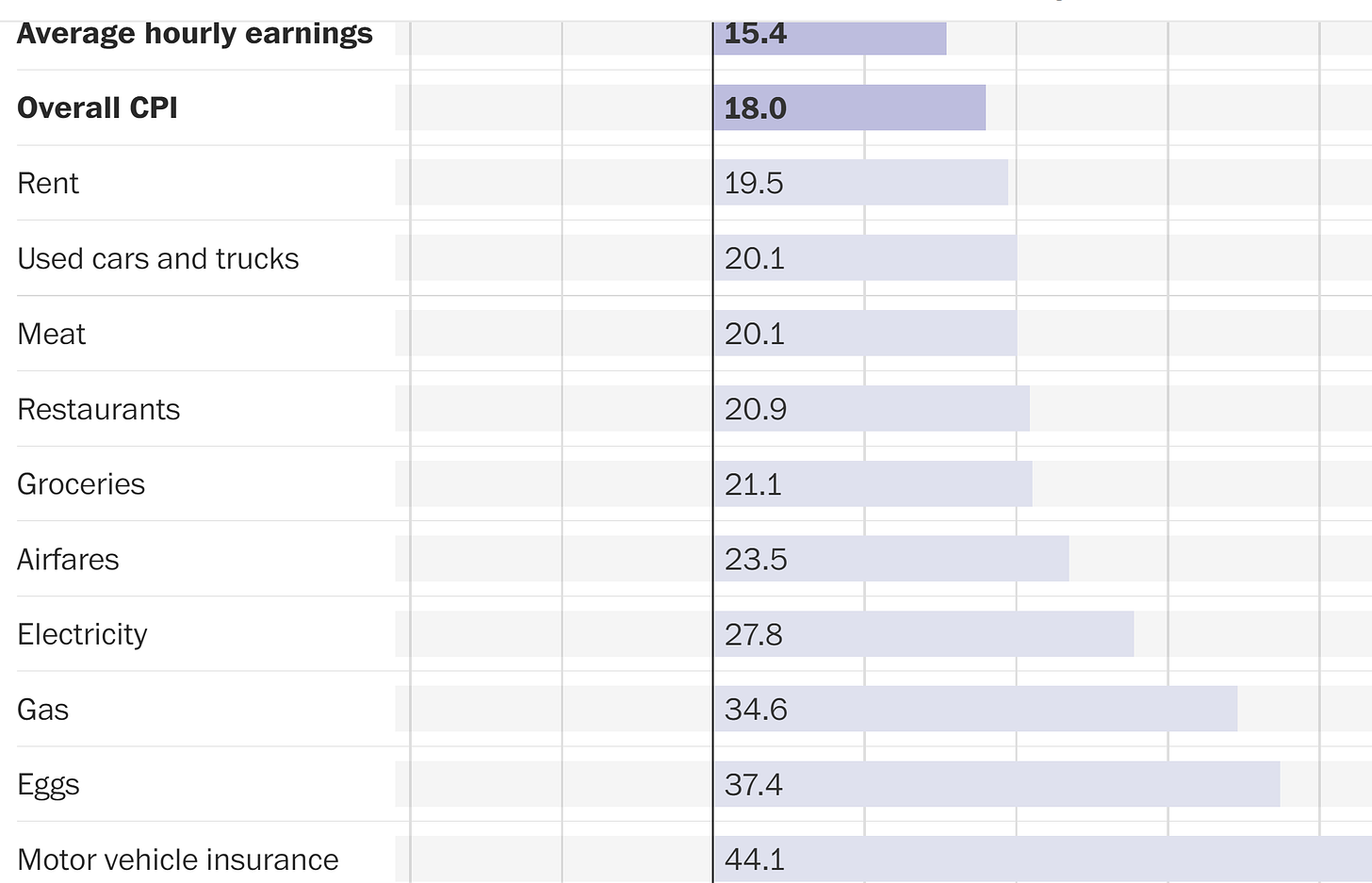

But there’s quite a strong case that, in terms of the “lived experience” of voters, particularly working-class voters, things have not in fact been great. The primary suspect of course is inflation which is still relatively high and in June of 2022 reached 9 percent, the highest inflation rate the country had experienced since 1981. People absolutely hate inflation since it directly undercuts living standards and they are reminded of this fact when they do mundane things like go to the grocery store. Heather Long of the Washington Post recently collected data on changes in inflation, hourly earnings and household purchases since Biden took office, shown below.

As the chart shows, cumulative inflation has outpaced average hourly earning growth and the rise in many consumer prices have been even larger than overall inflation: rent and meat (up 20 percent); restaurants and groceries (21 percent); electricity (28 percent); gas (35 percent); and eggs (37 percent). These are facts of economic life that voters have a hard time forgetting.

More broadly, economics commentator Roger Lowenstein reminds us that real median household income went up 10.5 percent under Trump before the pandemic hit. In contrast:

[Under Biden], inflation has snatched away the gains from even a very strong labor market. Over his first two years, as price hikes outran wages, real median household income fell 2.7 percent. The census has yet to report median income for 2023, but given that real wages were up about 1 percent through November, the cumulative change in household median income, adjusted for inflation, over Mr. Biden’s first three years is likely to be in the range of mildly negative to very mildly positive. In other words, in the all-important category of improving living standards, the country did not make progress.

This certainly helps explain why many voters look back fondly on the Trump economy while being quite negative about the Biden economy. It doesn’t matter whether Trump “caused” the strong economic performance on his watch—it’s still what voters experienced.

And there’s an additional factor that helps explain the depressed economic mood, even as some economic indicators have forged ahead. That is not just the cost of consumer goods but the “cost of money”. A new NBER working paper, “The Cost of Money is Part of the Cost of Living: New Evidence on the Consumer Sentiment Anomaly” by economists Marijn A. Bolhuis, Judd N. L. Cramer, Karl Oskar Schulz and Lawrence H. Summers finds that:

Unemployment is low and inflation is falling, but consumer sentiment remains depressed…We propose that borrowing costs, which have grown at rates they had not reached in decades, do much to explain this gap. The cost of money is not currently included in traditional price indexes, indicating a disconnect between the measures favored by economists and the effective costs borne by consumers. We show that the lows in US consumer sentiment that cannot be explained by unemployment and official inflation are strongly correlated with borrowing costs and consumer credit supply. Concerns over borrowing costs, which have historically tracked the cost of money, are at their highest levels since the Volcker-era. We then develop alternative measures of inflation that include borrowing costs and can account for almost three quarters of the gap in US consumer sentiment in 2023.

Put it all together and the deluded, ungrateful wretches theory seems increasingly untenable. However, the Democrats do have another economic argument which merits consideration. That is that they are playing the long game—laying the basis for future abundance.

They base this claim on the adoption of a new “industrial strategy”, as instantiated in the three big bills passed in Biden’s first two years: the Infrastructure and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the so-called Inflation Reduction Act (mostly a climate spending bill). These bills included $1.5 trillion in new spending to jump-start an economic transformation of the country built around the industries of the future, especially those related to clean energy.

That’s the theory and as theories go it’s not a bad one. Historically, America has worked best when public policy and private initiative have collaborated in service of great national goals. That goes all the way back to the early 19th century American System of infrastructure investment and industry promotion initiated by Alexander Hamilton and includes the great surge of innovation, widely-shared prosperity and American global leadership after World War II.

Thus aggressive public policy along these lines has considerable precedent and justification. But it doesn’t follow that Democrats today have the right strategy and are making the right investments. That’s an open question

What an industrial strategy or policy should accomplish is shifting a country’s output toward emerging industries that become competitively successful and spark overall economic growth and prosperity. Is that happening today? Are the Democrats, once again, on the verge of becoming the party of American prosperity?

Democrats say this is already happening and point to $200 billion in commitments by companies to projects in the semiconductor and clean energy areas. Of course, commitments are not the same as projects being completed but it is true that there has been a remarkable spike in manufacturing construction spending, more than doubling since August of 2022 when the IRA and CHIPS and Science bills were passed. Perhaps not surprisingly, there is an appetite for taking advantage of generous subsidies and tax credits.

But it is also true that growth in overall private investment is sluggish. The boom, such as it is, appears to be highly localized and sector-specific. Moreover, even in manufacturing, total employment has been almost flat since August, 2022 when the IRA/CHIPS and Science were passed; the lion’s share of manufacturing employment growth during the Biden administration has simply replaced jobs lost during the COVID crash. And as Noah Smith points out, manufacturing output hasn’t gone anywhere (in fact, it’s recently been going down) and the manufacturing sector may now even be in a slump.

As Smith also notes there are many obstacles in the way of successful industrial policy, which cannot and should not be reduced to spending a lot of money (“checkism”). Democrats will need considerable time to get it right and “bold, persistent experimentation” à la FDR. Not to mention some serious regulatory and permitting reform and the discarding by Democrats of their absurd commitment to “everything bagel liberalism.”

Here’s why: it’s just too damn hard to build stuff in this country. But Democrats seem more interested in spending money than changing this situation—for example, the modest permitting reforms that Joe Manchin was promised (remember that?) as a condition for his support on the IRA died partially because of lack of support from his own party. But without changing that situation, it’s quite unlikely Democrats can deliver the abundance voters, particularly working-class voters, are looking for. Making it a bit easier for consumers to buy an electric car or a heat pump just isn’t going to cut it.

It’s worth dwelling for a moment on the death of Manchin’s permitting reform and its implications. As has been widely noted, if the IRA’s investments are to actually reduce carbon emissions to the extent the administration and advocates claim, it would depend on an absolutely massive build-out of infrastructure, especially interregional high voltage transmission lines, which will be quite difficult. As noted, it’s very hard to build such things fast in the United States, given permitting and regulatory obstacles. Even with the permitting reform bill, the pace at which this infrastructure could plausibly have been built was likely far below what would be needed to hit administration timetables. Without permitting reform, the pace will be truly glacial.

And it’s not just renewable energy infrastructure that will suffer. There is now a renaissance in nuclear energy—theoretically supported by the IRA—throughout the world, as country after country reverses course and embraces the necessity of a nuclear buildout: the Czech Republic, Netherlands, Poland, South Korea, the UK, and even Japan, which had anathematized nuclear after the 2011 Fukushima incident. But the US will be hard-pressed to participate in this renaissance without regulatory changes that would facilitate the building of new reactors. Instead, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission released a draft of new rules in September, 2022 that would make it harder, not easier, to build them.

Yet without adequate infrastructure and firm power supply from nuclear or fossil fuels, the rapid build-out of wind and solar the Biden administration and climate advocates want is highly unlikely to work the way they envision. But it will stress the grid and likely anger consumers and industry through rising prices and declining reliability.

And Democrats should remember this: working-class voters do not share Democratic elites’ zeal for restructuring the economy around “green” industries and a clean energy transition based around wind, solar and electric vehicles which underpins much of the Democrats’ new industrial strategy. Working-class voters are much more pragmatic and will judge this strategy not by its greenness but by its concrete effects on their lives.

That is the way—the only way—Democrats can truly become the party of abundance American voters are looking for. Right now, they surely are not. Consider that for 74 years, Gallup has been asking a question about which party can do a better job “keeping the country prosperous” in the next several years. In the first part of this period, from 1951 to the election of Ronald Reagan, Democrats had a large and robust advantage on this measure, averaging a 17-point lead over the Republicans. But from the Reagan election on, that advantage has vanished. While there have been many ups and downs, Republicans have averaged a slight advantage (two points) on which party can keep the country prosperous. The last two readings, in fall of 2022 and fall of 2023, had Republicans preferred over the Democrats by 10 and 14 points points, respectively. And among working-class voters, the gap was vast in the last reading: 60 percent of these voters preferred the Republicans and just 33 percent the Democrats.

It would appear that Democrats seriously need to rethink their economic approach and not assume that simply spending more money in their favorite areas (like climate change) is going to do the job. It won’t. Voters are a much tougher audience than that.