Kyle Kondik explains “The Third Party Wild Card: Recent non-major party vote strongest out west — and not in the states likeliest to decide 2024” at Sabato’s Crystal Ball:

In addition to RFK Jr., left-wing intellectual Cornel West is also running, most recently deciding to run as a true independent instead of seeking the Green Party nomination. No Labels, the third party group that Democrats see as a front for Republicans trying to hurt Joe Biden through the party’s potential candidacy, is also floating out there. And that doesn’t even mention the Green and Libertarian parties, the two most reliable sources of third party candidates in recent years, or anyone else who might run.

None of these candidates, individually, would have a prayer of winning barring some truly incredible change in American politics, nor are they even guaranteed to be on the ballot everywhere. Collectively, though, the level of support they get will be interesting to monitor, and it may be that the third party vote ends up disproportionately hurting one of the major party nominees over the other, although that is not certain. At least two recent polls, from USA Today/Suffolk and NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist, showed Donald Trump doing better on the two-way ballot against Biden than if Kennedy was included (although the effect is more pronounced in the Marist survey). But after using Kennedy as a weapon against Biden in the Democratic primary, Republicans are switching gears as he now appears to threaten Trump more.

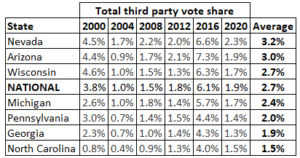

In terms of Electoral College votes in key swing states, however, the third party vote could be less consequential. Kondik argues that ” Of greatest interest to us is whether we should expect the third party vote to be meaningfully higher or lower in the most important states in the Electoral College. Seven states were decided by 3 points or less in 2020: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin — these states form the core of what we expect to be the competitive map in 2024. Their recent third party history is shown in Table 3.

Kondik notes further that “Pennsylvania and Michigan are also on the lower end of the average — the Keystone State was just a couple hundredths of a point from being listed in the bottom 10 of average third party voting in Table 2. Wisconsin is basically right at the average, and Arizona is a little above average, with the big third party year of 2016 standing out as its strongest outlier year (and even then, the third party share was only a little over a point higher than the nation as a whole). Of these core swing states, Nevada has had the highest average third party vote in recent elections. Nevada offers voters an explicit “None of These Candidates” option, which likely contributes to the higher average: This option has gotten at least 0.4% of the vote in every election this century, and that’s about how much higher Nevada’s average third party voting is compared to the rest of the country. Arizona and Nevada being a little higher than average also just fits in with them being western states, given the heightened support that recent third party candidates have gotten in that region.”

Kondik concludes, “So, while there are a number of states that have a recent track record of clearly higher-than-average third party performances, the states most likely to decide the election are not really among them. That doesn’t mean third party votes in these states are necessarily unimportant: It just means that we shouldn’t expect the third party candidates to do better in them than they do nationally. It may also be that a common argument against voting third party — “go ahead, throw your vote away,” to quote a favorite Simpsons episode — is perhaps most persuasive in the top battlegrounds.”