University of Pennsylvania poly sci professor Dan Hopkins explains “Why Trump’s Racist Appeals Might Be Less Effective In 2020 Than They Were In 2016” at FiveThirtyEight:

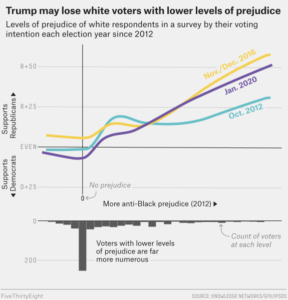

Looking at that panel survey I used in the Political Behavior study, we can see how the relationship between white respondents’ prejudice and their presidential intentions has changed. In the January 2020 survey wave, the poll included a question about a potential Trump-Biden general election match-up. And respondents who reported especially high levels of prejudice back in 2012 were roughly as firmly with Trump as of this January as they had been in fall 2016.4

But notice the histogram at the bottom, which show how many respondents registered each level of prejudice: The high-prejudice portion of the white electorate where Trump was clearly outperforming Romney accounts for roughly a quarter of all white respondents (to say nothing of nonwhite voters or voters too young to appear in a 12-year-old panel). Further activating this group is likely to have diminishing returns for Trump because there aren’t many of them and they are already strongly behind the president. By contrast, white voters with lower levels of prejudice are far more numerous, and also less likely to be with Trump than in 2016. In other words, Trump has far more room to increase his support among the larger number of white Americans with lower levels of prejudice.

Remember, this wave of the panel was conducted in January — before COVID-19 and, crucially, before the protests following the killing of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and the shooting of Jacob Blake. The protests may have changed the relationship between racial attitudes and voting in ways not detected in this survey. But the evidence to date suggests that, if anything, the protests may have continued to push white Americans’ racial attitudes in a liberal direction. And as Tesler contends, Democrats are now arguably more unified on race-related issues than Republicans, meaning that relative to 2016, there are fewer voters with the mix of attitudes that might make them responsive to racial appeals. Other issues, like the coronavirus and the government’s response, have also crowded the political agenda, limiting Trump’s ability to change the subject.

True, Grimmer and Marble disagree with Sides, Tesler and Vavreck on the role racial attitudes played in 2016. But when looking ahead to 2020, the researchers are more in agreement. In an email, Grimmer offered a conclusion similar to Tesler’s, noting that “in 2016, Trump was already winning almost all of the declining fraction of voters who are highest in racial resentment. So he has a lot more room for growth among those in the middle of the racial resentment scale, both in terms of turning out and choosing him over Biden.”

It’s surely too soon to count Trump out. But if Trump does win reelection in November, it’s very likely to be due to gains with white voters lower in prejudice or with nonwhite voters. Using racist appeals and racialized wedge issues won him support most clearly in the 2016 GOP primary. But there are key differences between that contest and the 2020 general election — differences that may make racial appeals less impactful this year. And judging from the RNC’s periodic efforts to counter the charge that Trump is racially divisive, some of its planners seem to agree.

Trump’s racial fear-mongering may or may not gain him some support from voters with lower levels of racial resentment. Yet his support from this group may be limited further by the number of voters who are not willing to overlook his failure to address the pandemic and it’s disastrous effect on their economic well-being.