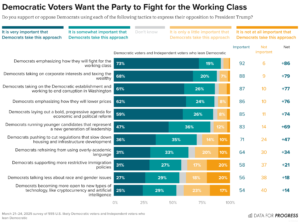

The following graph is cross-posted from ‘Data for Progress:

At Politico, Elena Schneider writes, “Rep. Greg Casar wants Democrats to “pick villains” in the GOP and drop purity tests in primaries…The Congressional Progressive Caucus chair, a 35-year-old Texas millennial who took over its leadership in December, thinks his party lost its working-class identity, while becoming too cautious and too boring in its fight against Republicans. He’s meeting privately with other members to discuss ways to steer the party toward a more populist economic message — being “known as the party of working people, first and foremost,” Casar said — and he’s mounting an aggressive public relations campaign to push it…Casar, along with Reps. Chris Deluzio (D-Penn.) and Pat Ryan (D-N.Y.), have been meeting informally with about a dozen Democratic members to talk about how best to shift the party into emphasizing economic populism..“Republican officials have figured out how to elevate social issues that impact only a small number of people and make them the dominant issues in elections,” Casar said. But after “knocking on thousands of doors” in Texas, even the most conservative voters “never opened the door and said, ‘Thank God you’re here. I want to talk to you about the appropriate level of testosterone for somebody to compete in the NCAA [sports].”…”If we’re willing to say…the richest people on the planet want to steal your Social Security check in order to enrich themselves and their friends, well, now you’re cooking with gas,” Casar said. “Be willing to explain that — to win a voter’s trust by telling people we are willing to actually go up against the villains that are screwing them over.”…“There’s a lot of different approaches to the economy that can appeal to working class voters, that involve honoring hard work, ensuring that everybody has an opportunity to earn a good life and that doesn’t involve ‘fighting the oligarchs,” [Third Way Founder Matt] Bennett said. “If that becomes their litmus test, then we’re right back in the same boat.”

In her “Letters from an American” Substack post for March 30, Heather Cox Richardson notes that “the top seven donors to the 2024 political, cycle together gave almost a billion dollars to Republicans, with Elon Musk alone contributing more than $291 million. The list, compiled by Open Secrets, shows that Democratic donors don’t kick in until number eight on the list, former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, who gave slightly more than $64 million to Democrats. George Soros, the Republicans’ supervillain, didn’t make the top 25. As those wealthy donors wish, the Trump administration is shredding the post–World War II government and has prioritized tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations…Trump is digging into the position that some people are better than others and have the right to rule. Today he told NBC News that he is considering a third presidential term, although that is explicitly unconstitutional. “I’m not joking,” he said, “There are methods which you could do it.”

At The Bulwark, Lauren Egan shares some observations about demographic change that will have a big impact on Democratic strategy in the near future: “Thanks to a decades-long flood of cross-country migration from states like California and New York to states like Texas and Florida, the South has emerged as an economic, political, and cultural powerhouse. Tech companies are relocating to Austin; movies are increasingly being produced in Atlanta; and more students from the Northeast are attending SEC schools—and then staying in the South after graduating—than ever before. The region accounted for more than two-thirds of all job growth across the United States since early 2020, and it now contributes more to the national GDP than the Northeast does…All of that means that the South is on track to make historic gains in the 2030 census. Florida and Texas are projected to gain four or more congressional seats, while North Carolina, Georgia, and Tennessee could each gain a seat. Meanwhile, reliably blue states like California could lose as many as five; New York might lose three. Illinois, Minnesota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin could also see declines…All told, nearly four in ten Americans could hail from the South by the next census, according to a recent Brennan Center analysis. That not only means the path to a House majority runs through the South—it also means the party’s reliance on the “Blue Wall” will no longer be viable in future presidential elections. (The number of Electoral College votes a state gets is determined by how many congressional districts it has.)”