Aside from having major implications for individual rights and perhaps for the Democratic Party, the current abortion fight may also affect the future of individual politicians, one of whom I wrote about at New York:

Vice-presidents of the United States are captive to their boss’s interests and the assignments they are willing to delegate. This has been particularly true of the current vice-president, Kamala Harris. She’s in the shadow of a generally unpopular president who has at best a shaky grip on his own party (most Democrats hope those negative characterizations of Joe Biden will soon be out of date, but they remain accurate right now). And as my colleague Gabriel Debenedetti recently explained, Harris has been unlucky with the thankless jobs Biden has given her:

“Her popularity started sinking when she first visited Central America and appeared dismissive of a suggestion that she visit the border. Behind the scenes, she was worried the assignment to take on the migrant crisis was a clear political loser … Her other top priority — voting rights — was no less publicly frustrating when the administration’s preferred legislation predictably failed in the split Senate. Some close to her wonder why she didn’t muscle her way into leading more popular projects: implementation of the COVID-relief-bill spending or, later, the infrastructure package.”

But now Harris’s luck may have finally turned: She is emerging as the Biden administration’s chief champion of abortion rights at a time when they are uniquely in danger and when Democrats everywhere are seizing on the issue as a potential game changer in 2022 and beyond. It’s an issue that fits her far better than it does the president, an old-school Irish Catholic politician who until mid-2019 opposed federal funding for abortions and could not bring himself even to say the word abortion. Harris is an entirely credible and consistent advocate for reproductive rights, as the Los Angeles Times noted:

“Taking command in the battle over abortion’s future, now largely being fought in the states and as an issue in the November election, comports neatly with Harris’ political résumé, touching on her experience as the first woman elected to the second-highest post in the nation and as a former California attorney general and U.S. senator with a longstanding interest in maternal health.”

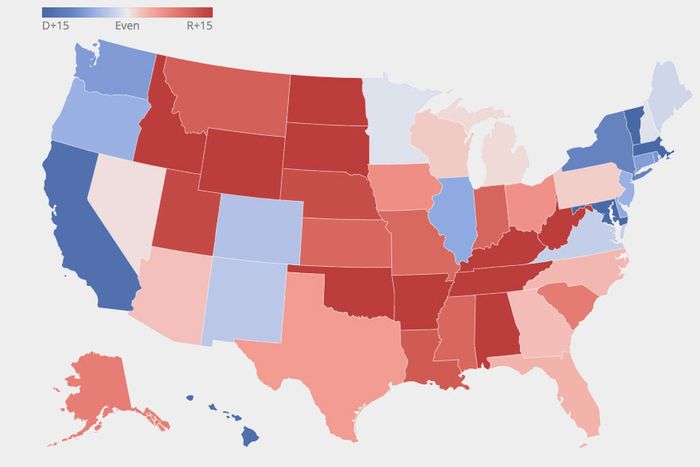

It’s also worth noting that the women most immediately and harshly affected by the anti-abortion legislation racing toward enactment in red states are people of color, Black and Asian American women like Harris. And although many other federal and state Democrats will command a portion of the bright spotlight on this topic, Harris uniquely can call on the unparalleled megaphone of the White House, which reaches all states with highly diverse abortion landscapes. Per the Times:

“’We need a leader on this. No one knows who’s the head of Planned Parenthood,’ said Montana state Sen. Diane Sands, an abortion rights activist since the 1960s and one of many Democratic lawmakers and advocates who have met with Harris in recent weeks.”

Most of all, the abortion-rights battle offers Harris something her 2020 presidential campaign lacked: a passionate constituency with national reach, as the Washington Post observes: “She faces considerable pressure to show that her political skills have improved since that effort, which collapsed before a single primary vote was cast.” Yes, she has the famously combative “KHive” Twitter army ready to throw down on her behalf at a moment’s notice, but she could use a showing of excitement in the non-virtual world of left-of-center grassroots activists too. No issue is more starkly partisan than abortion post-Dobbs; within the Democratic Party, there is no real downside to pro-choice militancy.

What would really benefit Harris politically, of course, would be evidence that the abortion issue can stop or significantly mitigate the red wave so many Democrats fearfully glimpse on the horizon of the November elections. If abortion rights turn out to be not simply an energizer for the Democratic Party’s progressive base but a wedge issue that can bring back the suburban gains and heavy youth turnout of the 2018 midterms, it could help give Harris’s prospects a significant boost.

This development for Harris couldn’t arrive at a better time. Biden’s rapidly approaching 80th birthday is very likely to revive pressure on him to retire at the end of his first term. At this point, even though Harris is the heir apparent as vice-president, it’s unclear whether she has enough political juice to head off powerful rivals for the 2024 nomination. Nothing would make her more powerful as a presidential contender than to have not just Biden’s blessing but a reputation for fighting on an issue of crucial importance to progressive politics and the people it aims to represent.