Christopher Ingraham’s Wonkblog post, “The non-religious are now the country’s largest religious voting bloc” provides a number of interesting observations about the role of religion in U.S. politics. It’s an evolving role, made more complicated by demographic transformations underway in particular states. But there are a couple of overriding points of interest, including:

More American voters than ever say they are not religious, making the religiously unaffiliated the nation’s biggest voting bloc by faith for the first time in a presidential election year. This marks a dramatic shift from just eight years ago, when the non-religious were roundly outnumbered by Catholics, white mainline Protestants and white evangelical Protestants.

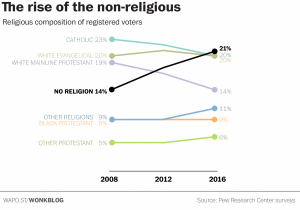

These numbers come from a new Pew Research Center survey, which finds that “religious ‘nones,’ who have been growing rapidly as a share of the U.S. population, now constitute one-fifth of all registered voters and more than a quarter of Democratic and Democratic-leaning registered voters.” That represents a 50 percent increase in the proportion of non-religious voters compared with eight years ago, when they made up just 14 percent of the overall electorate.

My hunch is that it is a mistake to call the religiously unaffiliated a “voting bloc,” at least in the sense that they are not monolithic supporters of Democrats, Republicans or any other party. Indeed, as the above quote notes, only about one out of seven of them actually vote. It’s also a mistake to think of them as heathens, in that many will tell you they are believers, but they distrust “organized religion.” So it’s not like all of those who bother to vote are casting ballots that reflect atheistic convictions.

Nor are the religiously-affiliated paragons of high voter turnout. (I kid you not, in an interesting coincidence a few mintues ago, I was interrupted by the knock on the door by a member of Jehova’s Witnesses, who do not vote at all as a matter of principle.) Ingraham shares the following Pew Research Center chart indicating the voter registration trends of the religiously affiliated subgroups and unaffiliated since 2008:

So the misnamed non-religious Americans are now 21 percent of registered voters, a 50 percent uptick from 2008, while “other religions” have increased their share of RVs from 9 to 11 percent and Catholics, white evangelical protestants and white mainline protestants have seen a decline in their share of the nation’s RVs.

Ingraham adds further,

The growth of the non-religious — about 54 percent of whom are Democrats or lean Democratic, compared with 23 percent at least leaning Republican — could provide a political counterweight to white evangelical Protestants, a historically powerful voting bloc for Republicans. In 2016, 35 percent of Republican voters identify as white evangelicals, while 28 percent of Democratic voters say they have no religion at all.

It doesn’t seem like this alone will force much change at the ballot box, especially in the context of 2016 politics. Trump, for example, is doing well with white evangelicals at the moment. But it’s not hard to imagine a significant decline in their support for him once the ad campaigns hit high gear and media coverage makes voters more aware of the Trump’s lifestyle and their minimal religious involvement.

Ingraham cites the “underperformance of the non-religious” at the ballot box as a key factor. But that should be a washout for the two parties, neither one reaping much advantage because of it. There is not much that can be done to target them as a group, outside of crafting political ads, even if their politics were monolithic, which is not the case.

But Dems should keep an eye on Latino Christian voters, many of whom may be inspired by Pope Francis’s commitment to social activism, coupled with Trump’s animosity towards their aspirations. Latino organizations are important, but it would be a mistake to assume they alone can increase voter turnout and ignore the Hispanic churches.

Even more consequential, however, are the votes of African American Christians, who tend to cast their ballots favoring Democrats by as much as a 9 to 1 ratio. The ‘Souls to the Polls’ movement could be influential this year, particularly in states that have not enacted voter supression measures to squeeze early voting opportunities and registration deadlines. The Republicans fear the ‘Souls to the Polls’ movement as much as any religious trend in America, and there is not much they won’t do to obstruct it, legal and otherwise.

There has been speculation recently that even Georgia could be in play in 2016 in terms of electoral votes, owing to the accelerating demographic transformation favoring Democrats in recent years. I will be surprised if that happens. But if it does, credit ‘Souls to the Polls’ and Black church activism in Georgia.

The late Rev. James Orange, one of the AFL-CIO’s star union organizers, once told me that the first thing he does when he begins a labor campaign anywhere in the south is visit the most influential preachers in town and make an appointment to meet with their congregations. No doubt the same should be true for Democratic political candidates. Clinton should work every major African American church in NC, FL and GA, and really in all of the swing states.

The Clintons have thus far done an excellent job of leveraging the power of the African American electorate in this campaign. For the remainder of the campaign, however, an even more energetic outreach to Black and Latino congregations can lead the way to victory in November.

Latino congregations could be a mixed bag for Dermocrats. One of the reasons Pope Francis was chosen was Catholic concerns about the rapid spread of Protestant evangelicism in Latin America. Democrats should be careful about which congregations they court in the U.S., since some Latino cleregy may be tilting towatd the GOP.